Thierry H. LeJemtel, MD

- Department of Medicine

- Division of Cardiology

- Tulane University School of Medicine

- New Orleans, LA

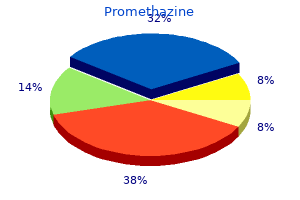

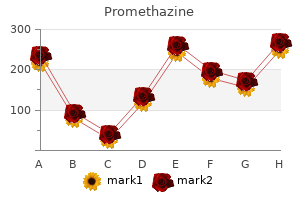

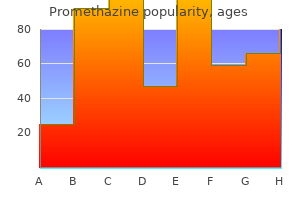

Repeat the procedure using IgA instead of IgG-coated beads and anti-IgA instead of anti-IgG antibodies allergy shots maintenance order cheap promethazine on-line. The m otile sperm atozoa will initially be seen m oving around with a few or even a group of particles attached allergy medicine children under 6 cheap promethazine 25 mg visa. Eventually the agglutinates becom e so m as sive that the m ovem ent of the sperm atozoa is severely restricted allergy treatment kochi buy cheap promethazine on line. Sperm that do not have coating antibodies will be seen swim m ing freely between the particles allergy treatment elderly buy discount promethazine on line. The goal of the assay is to determ ine the percentage of m otile sperm atozoa that have beads attached to them allergy testing eczema buy promethazine with amex. Score only m otile sperm atozoa and determ ine the percentage of m otile sper m atozoa that have two or m ore latex particles attached allergy symptoms on skin buy promethazine pills in toronto. Evaluate at least 200 m otile sperm atozoa in each replicate, in order to achieve an acceptably low sam pling error (see Box 2. Record the class (IgG or IgA) and the site of binding of the latex particles to the sperm atozoa (head, m idpiece, principal piece). Note 1: If 100% of m otile sperm atozoa are bead-bound at 3 m inutes, take this as the test result; do not read again at 10 m inutes. Note 2: If less than 100% of m otile sperm atozoa are bead-bound at 3 m inutes, read the slide again at 10 m inutes. Note 3: If sperm atozoa are im m otile at 10 m inutes, take the value at 3 m inutes as the result. Pending additional evidence, this m anual retains the consensus value of 50% m otile sperm atozoa with adherent particles as a threshold value. Com m ent: Sperm penetration into the cervical m ucus and in-vivo fertilization tend to be signi? The binding of beads with anti-hum an IgG or IgA to m otile sper m atozoa indicates the presence of IgG or IgA antibodies on the surface of the sperm atozoa. Transfer the required am ount of sem en to a centrifuge tube and m ake up to 10m l with buffer I. Sem en should be from m en with and without anti-sperm antibodies, respectively, as detected in previous direct im m unobead tests. M ix each anti-IgG im m unobead and sperm droplet together by stirring with the pipette tip. Store the slides horizontally for 3?10 m inutes at room tem perature in a hum id cham ber. Do not wait longer than 10 m inutes before assessing the slides, since im m unobead binding decreases signi? Score only m otile sperm atozoa that have one or m ore beads bound, as described in Section 2. Com m ent: the diagnosis of im m unological infertility is m ade when 50% or m ore of the m otile sperm atozoa (progressive and non-progressive) have adherent particles (Barratt et al. Particle binding restricted to the tail tip is not associated with im paired fertility and can be present in fertile m en (Chiu & Cham ley, 2004). Inactivate any com plem ent in the solublized cervical m ucus, serum, sem inal plasm a or testicular? M en who have had a vasectom y can be a source of serum if positive (>50% m otile sperm atozoa with bead binding, excluding tail-tip binding). A detailed assess m ent of the incidence of m orphological abnorm alities m ay be m ore useful than a sim ple evaluation of the percentage of m orphologically norm al sperm atozoa, especially in studies of the extent of dam age to hum an sperm atogenesis (Jouan net et al. Recording the m orphologically norm al sper m atozoa, as well as those with abnorm alities of the head, m idpiece and principal piece, in a m ultiple-entry system gives the m ean num ber of abnorm alities per sperm atozoon assessed. Laboratory cell counters can be used, with the num ber of entry keys adapted to the type of index being assessed. All the head, m idpiece and principal piece anom alies are included in the calculation. It incorporates several categories of head anom aly but only one for each m idpiece and principal piece defect. Of 200 sperm atozoa scored with a six-key counter for replicate 1, 42 were scored as norm al and 158 as abnorm al. Of the 158 abnorm al sperm atozoa, 140 had head defects, 102 m idpiece defects, 30 principal piece defects, and 44 excess residual cytoplasm. Results from replicate 2 were: 36 norm al and 164 abnorm al, of which 122 had head defects, 108 m idpiece defects, 22 principal piece defects, and 36 excess residual cytoplasm. Im m u nocytochem ical staining is m ore expensive and tim e-consum ing than assessing granulocyte peroxidase activity, but is useful for distinguishing between leuko cytes and germ cells. By changing the nature of the prim ary antibody, this general procedure can be adapted to allow detection of dif ferent types of leukocyte, such as m acrophages, m onocytes, neutrophils, B-cells or T-cells, should they be the focus of interest. Fixative: acetone alone or acetone/m ethanol/form aldehyde: to 95m l of acetone add 95m l of absolute m ethanol and 10m l of 37% (v/v) form aldehyde. Fix the air-dried cells in absolute acetone for 10 m inutes or in acetone/ethanol/ form aldehyde for 90 seconds. The slides can then be stained im m ediately or wrapped in alum inium foil and stored at ?70 ?C for later analysis. Store the slide horizontally for 30 m inutes at room tem perature in a hum id cham ber. Cover the sam e area of the sm ear with 10Pl of secondary antibody and incu bate for 30 m inutes in a hum id cham ber at room tem perature. Incubate with 10Pl of naphthol phosphate substrate for 20 m inutes in a hum id cham ber at room tem perature. Counterstain for a few seconds with haem atoxylin; wash in tap water and m ount in an aqueous m ounting m edium (see Sections 2. Assess the second sm ear in the sam e way (until 200 sperm atozoa have been counted). In this case, report the sam pling error for the num ber of cells counted (see Table 2. As fewer than 400 cells were counted, report the sam pling error for 60 cells given in Table 2. Com m ent: the total leukocyte num ber (total num ber of leukocytes in the ejaculate) m ay re? The length of tim e during which sperm atozoa can penetrate cervical m ucus varies considerably am ong wom en, and m ay vary in the sam e individual from one cycle to another. Note: See Appendix 5 for details of collection, storage and evaluation of the char acteristics of cervical m ucus. Com m ent: When a m an cannot provide a sem en sam ple, the postcoital test (see Section 3. It is im por tant that the m ucus is evaluated in the laboratory at a standard tim e? between 9 and 14 hours after coitus. W ith a tuberculin syringe (without needle), pipette or polyethylene tube, aspirate as m uch as possible of the sem inal? W ith a different syringe or catheter, aspirate as m uch m ucus as possible from the endocervical canal. The depth of this preparation can be standardized by sup porting the coverslip with silicone grease or a wax?petroleum jelly m ixture (see Box 3. Note: For reliable results it is crucial that the m ucus sam ple is of good quality and free of blood contam inants. M elt wax (48?66 ?C m elting point) in a beaker and m ix in petroleum jelly (approxim ately one part wax to two parts jelly) with a glass rod. W hile it is still warm, draw it into a 3-m l or 5-m l syringe (without a needle). Som e 2?3 hours after coitus there is a large accum ulation of sperm atozoa in the lower part of the cervical canal. The estim ate of the num ber of sperm atozoa in the cervical m ucus is traditionally based on the num ber counted per high-power m icroscope? The concentration of sperm atozoa within the m ucus should be expressed as the num ber of sperm atozoa per Pl. In this case r = 250Pm, r2 = 62 500Pm 2, Sr2 = 196 375Pm 2 and the volum e is 19 637 500Pm 3 or about 20 nl. However, as the total num ber of cells counted is low, the sam pling error is high. The m ost im portant indicator of norm al cervical function is the presence of any sperm atozoa with progressive m otility. Note: If the initial result is negative or abnorm al, the postcoital test should be repeated. Com m ent 1: If no sperm atozoa are found in the vaginal pool sam ple, the couple should be asked to con? A test perform ed too early or too late in the m enstrual cycle m ay be negative in a fertile wom an. In som e wom en, the test m ay be positive for only 1 or 2 days during the entire m enstrual cycle. When ovulation cannot be predicted with a reasonable degree of accuracy, it m ay be necessary to repeat the postcoital test several tim es during a cycle or to perform repeated tests in vitro. These tests are usually perform ed after a negative postcoital test, and are m ost inform ative when carried out with cross-over testing using donor sem en and donor cervical m ucus as controls. Com m ent 1: Donor cervical m ucus can be obtained at m id-cycle from wom en who are scheduled for arti? The cervical m ucus should be collected prior to insem ination, in natural cycles or in cycles in which ovulation has been induced by treatm ent with gonadotrophins. Com m ent 2: W om en can be given ethinyl estradiol for 7?10 days to produce estro genized m ucus for testing (see Appendix 5, section A5. Com m ent 3: W om en who are receiving clom ifene for induction of ovulation should not be used as cervical m ucus donors, because of the possible effects of this anti estrogen on the cervix. If the pH is m easured in situ, care should be taken to m easure it correctly, since the pH of exocervical m ucus is always lower than that of m ucus in the endocervical canal. Acidic m ucus im m obilizes sperm atozoa, whereas alkaline m ucus m ay enhance m otil ity. Note: Surrogate gels, such as bovine cervical m ucus or synthetic gels, cannot be regarded as equivalent to hum an cervical m ucus for in-vitro testing of sperm ?cervi cal m ucus interaction. However, the use of these m aterials does provide inform ation on sperm m otility within viscous m edia (Neuwinger et al. Deposit a drop of sem en at each side of the coverslip and in contact with its edge, so that the sem en m oves under the coverslip by capillary forces. In this way, clear interfaces are obtained between the cervical m ucus and the sem en. In m any instances, a single sperm atozoon appears to lead a colum n of sper m atozoa into the m ucus. Once in the cervical m ucus, the sperm atozoa fan out and appear to m ove at random. Som e return to the sem inal plasm a, but m ost m igrate deep into the cervical m ucus until they m eet resistance from cellular debris or leukocytes. Sperm atozoa are m otile (note the approxim ate percentage of m otile sperm ato zoa and whether they are progressively m otile). Consequently, it gives only a qualitative assessm ent of sperm ?m ucus interaction. Norm al result: sperm atozoa penetrate into the m ucus phase and m ore than 90% are m otile with de? Poor result: sperm atozoa penetrate into the m ucus phase, but m ost do not progress further than 500Pm (i. Phalanges m ay or m ay not be form ed, but the sperm atozoa congregate along the sem en side of the interface. This suggests the presence of anti-sperm antibodies in the m ucus or on the surface of the sperm atozoa. The test m easures the ability of sperm a tozoa to penetrate a colum n of cervical m ucus in a capillary tube. Glue onto a glass slide three reservoirs cut from sm all, plastic test tubes (radius about 3. Aspirate cervical m ucus into each capillary tube, m aking sure that no air bub bles are introduced. Seal one end of each tube with a capillary tube sealant, m odelling clay or sim ilar m aterial. Enough sealant should be applied so that the m ucus colum n protrudes slightly out of the open end of the tube. Place the open end of the capillary tube on the slide so that it projects about 0. Return the device to the 37 ?C incubator and inspect the capillary tubes again after 24 hours for the presence of progressing sperm atozoa. M igration distance: record the distance from the end of the capillary tube in the sem en reservoir to the furthest sperm atozoon in the tube. M igration reduction: this is calculated as the decrease in penetration density at 4. The m igration reduction value is zero because the penetration density has, in fact, increased (from rank order 5 to rank order 6) (Table 3. Sperm atozoa with forward m otility: determ ine the presence in the cervical m ucus of sperm atozoa with forward m otility at 2 and 24 hours 3. An infection can som etim es cause a decrease in the secretion of these m arkers, but the total am ount of m arkers present m ay still be within the norm al range. An infection can also cause irreversible dam age to the secretory epithelium, so that even after treatm ent secretion m ay rem ain low (Cooper et al. The am ount of zinc, citric acid (M ollering & Gruber, 1966) or acid phosphatase (Heite & W etterauer, 1979) in sem en gives a reliable m easure of prostate gland secretion, and there are good correlations between these m arkers. There are two isoform s of D-glucosidase in the sem inal plasm a: the m ajor, neutral form originates solely from the epidi dym is, and the m inor, acidic form, m ainly from the prostate. A sim ple spectro photom etric assay for neutral D-glucosidase is described in Section 3.

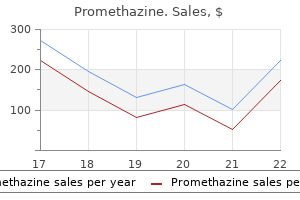

Consultation and/or co-management with a kidney disease care team is advisable during Stage 3 dust allergy symptoms uk order promethazine 25mg without prescription, and referral to a nephrologist in Stage 4 is recommended allergy testing symptoms cheap promethazine 25mg mastercard. Amultidisciplinary team approach may be necessary to implement and coordinate care allergy zithromax symptoms order generic promethazine canada. This classification could then be transformed to an ?evidence model? for future development of additional practice guidelines regarding specific diagnostic evaluations and therapeutic interven tions (Executive Summary) allergy treatment center buy genuine promethazine online. The Work Group sought to develop an ?evidence base? for the classification and clinical action plan allergy shots experience order 25 mg promethazine overnight delivery, derived from a systematic summary of the available scientific litera ture on: the evaluation of laboratory measurements for the clinical assessment of kidney disease; association of the level of kidney function with complications of chronic kidney disease; and stratification of the risk for loss of kidney function and development of cardiovascular disease allergy treatment canada buy discount promethazine. Two products were developed from this process: a set of clinical practice guidelines regarding the classification and action plan, which are contained in this report; and an evidence report, which consists of the summary of the literature. The Work Group consisted of ?domain experts,? including individuals with expertise in nephrology, epidemiology, laboratory medicine, nutrition, social work, pathology, gerontology, and family medicine. In addition, the Work Group had liaison members from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases and from the National Institute on Aging. The first task of the Work Group members was to define the overall topic and goals, including specifying the target condition, target population, and target audience. They then further developed and refined each topic, literature search strategy, and data extraction form (described below). The Work Group members were the principal reviewers of the literature, and from these detailed reviews they summarized the available evidence and took the primary roles of writing the guidelines and rationale statements. The Evidence Review Team consisted of nephrologists (one senior nephrologist and three nephrology fellows) and methodologists from New England Medical Center with expertise in systematic review of the medical literature. They were responsible for coordi nating the project, including coordinating meetings, refinement of goals and topics, creation of the format of the evidence report, development of literature search strategies, initial review and assessment of literature, and coordination of all partners. The Evidence Review Team also coordinated the methodological and analytic process of the report, coordinated the meetings, and defined and standardized the methodology of performing literature searches, of data extraction, and of summarizing the evidence in the report. They performed literature searches, retrieved and screened abstracts and articles, created forms to extract relevant data from articles, and tabulated results. Throughout the project, and especially at meetings, the Evidence Review Team led discussions on systematic review, literature searches, data extraction, assessment of quality of articles, and summary reporting. Based on their expertise, members of the Work Group focused on the specific questions listed in Table 8 and employed a selective review of evidence: a summary of reviews for established concepts (review of textbooks, reviews, guidelines, and selected original articles familiar to them as domain experts) and a review of primary articles and data for new concepts. The development process included creation of initial mock-ups by the Work Group Chair and Evidence Review Team followed by iterative refinement by the Work Group members. The refinement process began prior to literature retrieval and continued through the start of reviewing individual articles. The refinement occurred by e-mail, telephone, and in-person communication regularly with local experts and with all experts during in-person meetings of the Evidence Review Team and Work Group members. Data extraction forms were designed to capture information on various aspects of the primary articles. Forms for all topics included study setting and demographics, eligibility criteria, causes of kidney disease, numbers of subjects, study design, study funding source, population category (see below), study quality (based on criteria appropriate for each study design, see below), appropriate selection and definition of measures, results, and sections for comments and assessment of biases. The various steps involved in development of the guideline statements, rationale statements, tables, and data extraction forms were piloted on one of the topics (bone disease) with a Work Group member at New England Medical Center. The ?in-person? pilot experience allowed more efficient development and refinement of subsequent forms with Work Group members located at other institutions. It also provided experi ence in the steps necessary for training junior members of the Evidence Review Team to develop forms and to efficiently extract relevant information from primary articles. Training of the Work Group members to extract data from primary articles subsequently occurred by e-mail as well as at meetings. Classificationof Stages Defining the stages of severity was an iterative process, based on expertise of the Work Group members and synthesis of evidence developed during the systematic review. The ideal study design to assess prevalence would be a cross sectional study of population representative of the general population. Criteria for evalua tion of cross-sectional studies to assess prevalence are listed in Table 150. The ideal study design for diagnostic test evaluation would be a cross sectional study of a representative sample of patients who are tested using the ?gold? 268 Part 10. Data from baseline assessments of patients enrolled in the Canadian Multicentre cohort study of patients with chronic kidney disease were used for Figures 28, 29, 36, 37, 38, 40, and 42. Studies that provided data for various levels of kidney function were preferred; how 270 Part 10. Members of the Work Group provided individual patient data that were used for some analyses. Stratificationof Risk (Prognosis) the appropriate study to assess the relationship of risk factors to loss of kidney function and development of cardiovascular disease would be a longitudinal study of a representa tive sample of patients with chronic kidney disease with prospective assessment of fac tors at baseline and outcomes during follow-up. Because it can be difficult to determine the onset of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, prospective cohort stud ies were preferred to case-control studies or retrospective studies. Clinical trials were included, with the understanding that the selection criteria for the clinical trial may have lead to a non-representative cohort. Appendices 271 known association between diabetes and cardiovascular disease, diabetic and nondiabetic patients were considered separately. The association between diabetic kidney disease and other diabetic complications was evaluated using reviews of cross-sectional studies and selected primary articles of cohort studies. Review articles, editorials, letters, or abstracts were not included (except as noted). Studies for the literature review were identified primarily through Medline searches of English language literature conducted between February and June 2000. These searches were supplemented by relevant articles known to the domain experts and reviewers. The Medline literature searches were conducted to identify clinical studies published from 1966 through the search dates. Development of the search strategies was an iterative process that included input from all members of the Work Group. Search strategies were designed to yield approxi mately 1,000 to 2,000 titles each. The searches were limited to studies on humans and published in English and focused on either adults or children, as relevant. In general, studies that focused on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis were excluded. Potential papers for retrieval were identified from printed abstracts and titles, based on study population, relevance to topic, and article type. In general, studies with fewer than 10 subjects were not included (except as noted). After retrieval, each paper was screened to verify relevance and appropriateness for review, based primarily on study design and ascertainment of necessary variables. Overall, 18,153 abstracts were screened, 1,110 articles were reviewed, and results were extracted from 367 arti cles. Detailed tables contain data from each field of the components of the data extraction forms. These tables are contained in the evidence report but are not included in the manuscript. Summary tables describe the strength of evidence according to four dimensions: study size, applicability depending on the type of study subjects, results, and methodological quality (see table on the next page, Example of Format for Evidence Tables). Within each table, studies are ordered first by methodological quality (best to worst), then by applicability (most to least), and then by study size (largest to smallest). Study Size the study (sample) size is used as a measure of the weight of the evidence. In general, large studies provide more precise estimates of prevalence and associations. Appendices 273 large studies are more likely to be generalizable; however, large size alone does not guarantee applicability. A study that enrolled a large number of selected patients may be less generalizable than several smaller studies that included a broad spectrum of patient populations. The study population is typically defined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In making this assessment, sociodemographic characteristics were considered, as were the stated causes of chronic kidney disease and prior treatments. Studies without a vertical or horizontal line did not provide data on the mean/median or range, respectively. For studies of prevalence, the result is the percent of individuals with the condition of interest. For diagnostic test evaluation, the result is the strength of association between the new measurement method and the criterion standard. Associations were represented according to the following symbols: the specific meaning of the symbols is included as a footnote for each table. Because studies with a variety of types of design were evaluated, a three-level classification of study quality was devised: 276 Part 10. The use of published or derived tables and figures was encouraged to simplify the presentation. Each guideline contains one or more specific ?guideline statements,? which are presented as ?bullets? that represent recommendations to the target audience. Each guideline contains background information, which is generally sufficient to interpret the guideline. A discussion of the broad concepts that frame the guidelines is provided in the preceding section of this report. Appendices 277 and classifications of markers of disease (if appropriate) followed by a series of specific ?rationale statements,? each supported by evidence. The guideline concludes with a discussion of limitations of the evidence review and a brief discussion of clinical applica tions, implementation issues and research recommendations regarding the topic. Strength of Evidence Each rationale statement has been graded according the level of evidence on which it is based (see the table, Grading Rationale Statements). Medline was the only database searched, and searches were limited to English language publications. Hand searches of journals were not performed, and review articles and textbook chapters were not systematically searched. In addition, search strategies were generally restricted to yield a maximum of about 2,000 titles each. However, important studies known to the domain experts that were missed by the literature search were included in the review. In addition, essential studies identified during the review process were also included. Exhaustive literature searches were hampered by limitations in available time and resources that were judged appropriate for the task. The search strategies required to capture every article that may have had data on each of the questions frequently yielded upwards of 10,000 articles. The difficulty of finding all potentially relevant studies was compounded by the fact that in many studies, the information of interest for this report was a secondary finding for the original studies. Due to the wide variety of methods of analysis, units of measurements, definitions of chronic kidney disease, and methods of reporting in the original studies, it was often very difficult to standardize the findings for this report. The prevalence of microalbuminuria and protein uria by age, sex, race, and diabetes are tabulated to show the frequency with which these abnormalities are present in the population. Standardized questionnaires were administered in the home, followed by a detailed physical examination at a Mobile Examination Center. Data on physiologic variation in creatinine were obtained in a sample of 1,921 participants who had a repeat creatinine measurement. The percent difference between the two creatinine measurements, a mean of 17 days apart, had a mean of 0. The mean serum creatinine for 20 to 39-year old participants without hypertension or diabetes was 1. College of American Pathologists Survey data, released with permission of both laboratories, show that creatinine values in the White Sands laboratory measured during 1992 to 1995 using the Hitachi 737 instrument averaged 0. The latter values were similar to the overall mean of all laboratories for creatinine. Statistics focused on percentiles of the distribution to further decrease the influence of such outliers. Proteinuria A random spot urine sample was obtained from each participant aged 6 years and older, using a clear catch technique and sterile containers. Urine samples were placed on dry ice and shipped overnight to a central laboratory where they were stored at 20 C. Urinary albumin concentration was measured by solid-phase fluorescent immunoas say. Sex specific cutoffs were used to define microalbuminuria and albuminuria in a single spot urine. Our estimates reflect the prevalence of albuminuria based on a single untimed urine specimen and include individuals with persistent albuminuria and individuals with inter 280 Part 10. Agreement between the initial and repeat tests classified as normal, micro, and macro albuminuria was 91. Microalbuminuria persisted in the second visit in 57% and macroalbuminuria was present in another 4% of the 110 participants with microalbuminuria on the first exam. The variation in persistence by age group and sexwas: 45% at 20 to 39 (n 22), 59% at 40 to 59 (n 32), 70% at 60 to 79 (n 43), and 44% at 80 years (n 9), 65% among men (n 48), and 52% among women (n 62). Among 1,099 individuals without microalbuminuria at the first visit 5% (n 56) had microalbuminuria or albuminuria on the second visit. Blood Pressure Blood pressure measurements were obtained three times during the home interview and another three times during the examination and averaged. Individuals were classified as hypertensive if they had a mean blood pressure 140 mm Hg systolic, or 90 mm Hg diastolic, or reported being currently prescribed medication for hypertension treat ment. The primary analysis stratified individuals based on a history of diagnosed diabetes mellitus since this informa tion was available for nearly all individuals and could be used by physicians for risk stratification.

Exhaustion Exhaustion is short lived and affects those parts of the body that have been involved in the resistance stage allergy medicine for asthma order promethazine online pills. If the combination of resistance and exhaustion continues without relief over a long period allergy symptoms 4 weeks purchase promethazine in india, physical symptoms may develop such as raised blood pressure allergy treatment and high blood pressure promethazine 25mg fast delivery, headaches or indigestion allergy forecast tacoma wa promethazine 25 mg cheap. Stressors the total stress that can be imposed on the individual can be considered to come from four sources: 1 allergy symptoms 7dpo buy discount promethazine 25 mg. Environmental (physical) these stressors are related to normal events that may occur during flying operations allergy forecast kalamazoo purchase promethazine 25mg mastercard. Others are directly related to the tasks involved in flying and the degree of stress will vary from flight to flight, and for different stages of the flight. Temperature: 20 deg C is considered a comfortable temperature for most people in normal clothing. Greater than 30 deg C leads to increased heart rate, blood pressure and sweating whereas less than 15 deg C leads to discomfort, loss of feeling in the hands and poor control of fine muscle movement. For example, the natural resonance of the eyeball is 30 40 Hz, and the skull is 1-4 Hz. Noise: Sound over 80 dB can impair task performance and over 90 dB there is measurable impairment of the task. However, it has been shown that in some situations performance of vigilance tasks can actually be better in high noise levels than in low levels because noise can increase arousal levels. They are wide ranged and may include such factors as domestic, social, emotional or financial pressures which most people face on a recurring basis. Family arguments, death of a close relative, inability to pay bills, lifestyle and personal activities, smoking or drinking to excess and other factors which may affect physical and mental health, all contribute to life stress which is part of everyday living. These can add significantly to the operational stressors, which are part of flying activities. Stress can also arise from physiological factors such as hunger, thirst, pain, lack of sleep and fatigue. One such scheme scores stress by totalling points, as follows: Death of a spouse or partner 100 Divorce 73 Marital separation 65 Death of a close family member 63 Personal injury or illness 53 Loss of job 47 Retirement 45 Pregnancy 40 Sexual problems 40 Son or daughter leaving home 29 Change of residence 20 Bank loan or credit card debt 17 Vacation 13 Minor law violation 11 the cumulative points score gives an indication of life stress, but such schemes need to be treated with caution because of wide individual variability. Examples in aviation are encountering wind shear on finals or running short of fuel. These are the types of stressors that can cause startles, alarm reactions and fight or flight responses. Organisational Stress can arise from within the company or organisation for which an individual works. It can be avoided when the company is proactive in giving attention to the listed factors, and provides support for employees. Each individual has a personal stress limit and if this is exceeded, stress overload occurs which can result in an inability to handle even moderate workload. For example, some individuals have the ability to switch off and relax, thus reducing the effects of stressors. Others are not so well equipped and the stress level increases to an unacceptable degree. When it happens to individuals working in a safety related environment, such as flight crew, air traffic controllers or aircraft engineers, it can have serious effects in terms of flight safety. It is common for an individual to believe that admitting to suffering from pressure is an admission of failure of ability to meet the demands of the job. It has long been an accepted culture in aviation that flight crew and others should be able to cope with any pressure or any situation, and training is directed at developing this capability in the individual the ?can do? attitude. Sometimes an individual, or his or her managers, will fail to recognise or accept the emerging existence of stress-related symptoms. Once the symptoms are apparent, behavioural changes such as aggression or alcohol dependence may become established. Such behaviour may lead to disciplinary action, which could have been avoided by early recognition of the developing situation and appropriate intervention and support. Anxiety and its Relationship to Stress Anxiety creates worry, and in turn any form of worry may lead to stress. Anxiety can be produced when an individual knows that they have no control over events or lack the knowledge to handle them. It is particularly prevalent in people who, for one reason or another, are lacking in self-confidence. This can be changed by increasing knowledge and gaining greater proficiency in operating an aircraft, requiring more time devoted to study and flight training. Stress and anxiety are an inevitable part of human life and in small quantities they are necessary to achieve optimum performance. On the other hand excessive stress levels lead to excessive anxiety and it is important that individuals are able to recognise this. Apart from the effects on behaviour, such as aggression, irritability, dogmatism and frustration, various psychological mechanisms may come into play in an attempt to cope with the situation. These make many of the human vulnerabilities discussed in other sections more likely, and include the following: Omission Omitting a particular action, such as failing to lower the landing gear during an approach with high workload and additional distractions; Error Incorrect response to a given stimulus, such as switching off the anti-collision beacon instead of the electric fuel pump; Queuing Sequentially delaying necessary actions in an inappropriate order of attention priority, such as failing to action a check list while dealing with complicated air traffic control instructions; Filtering Rejection of certain tasks because of overload, such as not identifying the navigation aids when setting up for an instrument approach, or failing to consciously hear R/T transmissions; Approximation Making approximations in technique in an attempt to cope with all the tasks required in a short-term interval, such as accepting inaccuracies while flying an instrument approach; Coning of attention With increasing stress, the attention scan closes in to a smaller field of awareness. It can be seen that many of the above relate to other areas of human factors such as workload, decision-making or error. In addition to the psychological effects of stress, physical effects may occur which vary from one individual to another. Stress is often interpreted by the brain as some form of threat, and indeed if being chased by a hungry sabre-toothed tiger it is a reasonable assumption. The ?fight or flight? response is when the primitive automatic responses for handling threatening situations come into play. The hormone adrenaline (epinephrine) is released, causing a rise in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate, deeper and more rapid breathing and an increase in tone of the larger muscle groups. Hormones known as corticosteroids are also released, making available stored sugars for increased energy use. Unfortunately this is often an inappropriate response because the situation has to be handled by mental rather than physical effort. Stress Management A certain amount of stress is unavoidable and indeed in certain conditions, it may be beneficial in raising arousal and hence improving performance. However, stress overload can reduce performance and it is helpful to consider ways of dealing with stress and reducing its effects. In determining fitness to fly, the psychological and emotional part of wellbeing must be considered in addition to the physical. Flying training engenders self-confidence and a strong desire to complete the task in hand. It can be difficult therefore to recognise and admit that one may be approaching the limit. The maintenance of physical wellbeing can assist in developing resistance to stress. Some can be handled just by recognising them by what they are and mentally putting them aside;? Do not allow low priority problems to influence when not intending to deal with them. Communicating and avoiding isolation is an effective way of lowering the level of stressors;? Eating regular balanced meals and indulging in physical activity several times a week promotes general health;? Finally, remember that clear thinking, free from emotional or physical worries, is essential for flight planning and the safe conduct of a flight. Coping Strategies Coping is the process in which the individual either adjusts to the perceived demands of a situation or changes the situation itself. Some of the strategies appear to be carried out subconsciously, and it is only when they are unsuccessful that the stressor is noticed. In this strategy the individual takes some action to reduce the stress either by removing the problem or altering the situation so that it becomes less demanding. This may be done by rationalisation or emotional and intellectual detachment from the situation. The effect is to change the perception of the problem even if the demand itself is no different. System Directing Coping this is a means of removing the symptoms of the stress by taking physical exercise, using drugs such as tobacco and alcohol or utilising other stress management techniques. Stress management is the process in which an individual will adopt systems to assist the coping strategies. Stress management techniques include: Health and fitness programmes Regular physical exercise assists some people with cognitive coping; Relaxation techniques There are many forms of relaxation frequently involving progressive muscle relaxation and the use of mental imagery. Examples include meditation, self-hypnosis, biofeedback techniques and autogenics. Some or all of these can be helpful in enabling individuals to reduce anxiety and control tension; Counselling techniques Counselling can assist both cognitive coping and action coping by modifying the way a situation is perceived leading to appropriate behavioural change. It may involve anything from regular sessions with a professional counsellor to simply taking about a stress problem with a supportive friend or colleague. As in all aspects of human factors, there is much variation between individuals and within the same individual. An understanding of the human response to stressors should assist in developing individual coping strategies. During sleep, sympathetic nervous activity decreases and the muscular tone becomes almost nil. The arterial blood pressure falls, the pulse rate decreases, the blood vessels in the skin dilate and the overall basal metabolic rate of the body falls by up to 20%. Studies have shown that up to 75% of adults report day time sleepiness, with nearly a third of them reporting severe levels which interfered with activities. As little as 2 hours of sleep loss can result in impairment of performance and levels of alertness. Sleep loss leads to increased reaction time, reduced vigilance, cognitive slowing, memory problems, time-on-task decrements and optimum response decrements. The normal sleep requirement is 8 hours in every 24-hour period, and it is possible to perform a simple calculation of sleep debt when this is not achieved. As the sleep requirement is 8 hours, within a 24 hour period this leaves 16 hours available for activity. Alternatively, this can be expressed as one sleep hour being good for two hours of wakeful activity. The maximum possible credit to offset against sleep debt is 8 sleep hours, meaning that no matter how long is spent sleeping, sleep debt will still begin occur after about 16 hours of continual wakefulness. It is not necessary to sleep for the exact number of hours in deficit to recover sleep debt. Most people find that a ?catch-up? sleep of around one third of the deficit is sufficient. Sleep debt can become cumulative, leading to a decrement in alertness and performance if the deficit is not recovered within a reasonable time. Sleep then becomes deeper with 15 minutes in stage 2 sleep and a further 15 minutes in stage 3 sleep before moving on to stage 4. Performance and alertness Besides sleep, the other major influence on waking performance and alertness is the internal circadian clock. Circadian rhythms fluctuate on a regular cycle which lasts something over 24 hours when allowed to ?free run. The circadian rhythms are controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus situated in the brain which is the time keeper for a wide range of human functions, including physiological performance, behavioural mood and sleepiness/alertness. Many body functions have their own circadian rhythm and they are synchronised to a 24 hour pattern by ?zeitgebers? (time givers). Light has been demonstrated as being the most powerful zeitgeber to synchronise the circadian pacemaker. In the normal rhythm, sleep would occur between 24:00 and 08:00 hours when body temperature is falling and reaching its low point. Therefore it is most difficult to work when body temperature is falling, and hardest to sleep when the body temperature is rising. This leads to a discrepancy between internal suprachiasmatic nucleus timing and external environmental cues. The internal clock can take days or weeks to readjust, but generally requires one day for each time zone crossed or one day for every 90 minutes of jet lag. Crossing time zones is a way of life for long-haul flight crew, and constant time zone shifts can lead to cumulative sleep deprivation due to disruption of the body cycles known as circadian desynchronosis. However, sleep debt and fatigue can also be problems for short-haul crew as a result of regular early morning starts and long multi-sector days. Long-haul crew have to constantly adjust and readjust circadian rhythms, and the various intrinsic rhythms for temperature, digestion and excretion get out of phase with the rhythm for sleep. Resynchronisation is easier when local time on landing is behind that at the airport of departure, whereas it is difficult when local time is ahead. It is vital that pilots and crew-members identify any sleep threat early on, because once sleepiness takes hold it can go unnoticed until too late. An ex-military pilot recounted that he had been on task in a prolonged auto hover at 40ft over the sea. He quickly looked around to see if anyone had noticed his slumber and to his horror he realised that the entire crew were sound asleep. It was late at night and the crew were on a prolonged surveillance task which involved hovering at altitude over a city. The commander recalled that after some time on task he had a sensation of falling and realised he had fallen asleep momentarily and lost control. In his startled state he stared at the attitude indicator but could make no sense of it or any of the other instruments to affect a recovery. This disorientation probably only lasted for a second or so but it felt like an age. The remainder of the crew, who had been focussed on the surveillance task throughout, were oblivious to the situation and calmly asked if they had encountered some turbulence. Therefore, in practical terms, there is little difference between chronic fatigue and acute tiredness.

The driver may encounter adverse road allergy forecast dfw purchase promethazine 25mg mastercard, weather allergy symptoms questionnaire promethazine 25mg fast delivery, and traffic conditions that cause unavoidable delays allergy medicine jitters promethazine 25mg with visa. Transporting hazardous materials allergy testing using hair samples discount promethazine 25 mg with mastercard, including explosives allergy medicine keeps me awake proven promethazine 25 mg, flammables allergy symptoms feel like flu trusted 25 mg promethazine, and toxics, increases the risk of injury and property damage extending beyond the accident site. Stay alert when driving this demands sustained mental alertness and physical endurance that is not compromised by fatigue or sudden, incapacitating symptoms. Required cognitive skills include problem solving, communication, judgment, and appropriate behavior in both normal and emergency situations. Driving requires the ability to judge the maximum speed at which vehicle control can be maintained under changing traffic, road, and weather conditions. Use side mirrors Mirrors on both sides of the vehicle are used to monitor traffic that can move into the blind spot of the driver. The act of steering can be simulated by offering resistance, while having the driver imitate the motion pattern necessary to turn a 24-inch steering wheel. Use of these components requires adequate reach, prehension, and touch sensation in hands and fingers. This requires the driver to repeatedly perform reciprocal movements of both legs coordinated with right arm and hand movements. Physical demands include grip strength, upper body strength, range of motion, balance, and flexibility. Vision and hearing are used to identify and interpret changes in vehicle performance. When a fatal crash involves at least one large truck, regardless of the cause, the occupants of passenger vehicles are more likely to sustain serious injury or die than the occupants of the large truck. The answer is found in basic physics: injury severity equals relative velocity change. The crash of a vehicle having twice the mass with a lighter vehicle equals a six-fold risk of death Page 21 of 260 to persons in the lighter vehicle. In addition to the grievous toll in human life and survivor suffering, the economic cost of these crashes is exceedingly high. As a medical examiner, your fundamental obligation is to establish whether a driver has a disease, disorder, or injury resulting in a higher than acceptable likelihood for gradual or sudden incapacitation or sudden death, thus endangering public safety. As a medical examiner, any time you answer ?yes? to this question, you should not certify the driver as medically fit for duty. Public Safety Consider Safety Implications As you conduct the physical examination to determine if the driver is medically fit to perform the job of commercial driving, you must consider: Physical condition o Symptoms Does a benign underlying condition with an excellent prognosis have symptoms that interfere with the ability to drive. Is the onset of incapacitating symptoms so gradual that the driver is unaware of diminished capabilities, thus adversely impacting safe driving? Nonetheless, you have a responsibility to educate and refer the driver for Page 24 of 260 further evaluation if you suspect an undiagnosed or worsening medical problem. Medical Examination Report Form Overview As a medical examiner, you must perform the driver physical examination and record the findings in accordance with the instructions on the Medical Examination Report form. The purpose of this overview is to familiarize you with the sections and data elements on the Medical Examination Report form, including, but not limited to: You are encouraged to have a copy of the Medical Examination Report form for reference as you review the remaining topics. As a medical examiner, you are responsible for determining medical fitness for duty and driver certification status. Health History the Driver completes and signs section 2, and the Medical Examiner reviews and adds comments: Figure 5 Medical Examination Report Form: Health History Health History Driver Instructions the driver is instructed to indicate either an affirmative or negative history for each statement in the health history by checking either the "Yes" or "No" box. The driver is also instructed to provide additional information for "Yes" responses, including: Health History Driver Signature Verify that the Driver signs Medical Examination Report Form: Figure 6 Medical Examination Report Form: Driver Signature Page 27 of 260 By signing the Medical Examination Report form, the driver: Regulations You must review and discuss with the driver any "Yes" answers For each "Yes" answer: As needed, you should also educate the driver regarding drug interactions with other prescription and nonprescription drugs and alcohol. Page 28 of 260 Health History (Column 1) Overview In addition to the guidance provided in the section above, directions specific to each category in Column 1 for each "Yes" answer are listed below. Feel free to ask other questions to help you gather sufficient information to make your qualification/disqualification decision. Any illness or injury in the last 5 years A driver must report any condition for which he/she is currently under treatment. The driver is also asked to report any illness/injury he/she has sustained within the last 5 years, whether or not currently under treatment. Seizures, epilepsy Ask questions to ascertain whether the driver has a diagnosis of epilepsy (two or more unprovoked seizures), or whether the driver has had one seizure. Gather information regarding type of seizure, duration, frequency of seizure activity, and date of last seizure. Eye disorders or impaired vision (except corrective lenses) Ask about changes in vision, diagnosis of eye disorder, and diagnoses commonly associated with secondary eye changes that interfere with driving. Complaints of glare or near-crashes are driver responses that may be the first warning signs of an eye disorder that interferes with safe driving. Ear disorders, loss of hearing or balance Ask about changes in hearing, ringing in the ears, difficulties with balance, or dizziness. Loss of balance while performing nondriving tasks can lead to serious injury of the driver. Obtain heart surgery information, including such pertinent operative reports as copies of the original cardiac catheterization report, Page 29 of 260 stress tests, worksheets, and original tracings, as needed, to adequately assess medical fitness for duty. High blood pressure Ask about the history, diagnosis, and treatment of hypertension. In addition, talk with the driver about his/her response to prescribed medications. The likelihood increases, however, when there is target organ damage, particularly cerebral vascular disease. As a medical examiner, though, you are concerned with the blood pressure response to treatment, and whether the driver is free of any effects or side effects that could impair job performance. Muscular disease Ask the driver about history, diagnosis, and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, such as rheumatic, arthritic, orthopedic, and neuromuscular diseases. Does the diagnosis indicate that the driver is at risk for sudden, incapacitating episodes of muscle weakness, ataxia, paresthesia, hypotonia, or pain? However, most commercial drivers are not short of breath while driving their vehicles. Health History (Column 2) Overview In addition to the guidance provided in the section above, directions specific to each category in Column 2 are listed below for each "Yes" answer. Lung disease, emphysema, asthma, chronic bronchitis Ask about emergency room visits, hospitalizations, supplemental use of oxygen, use of inhalers and other medications, risk of exposure to allergens, etc. Even the slightest impairment in respiratory function under emergency conditions (when greater oxygen supply is necessary for performance) may be detrimental to safe driving. Page 30 of 260 Kidney disease, dialysis Ask about the degree and stability of renal impairment, ability to maintain treatment schedules, and the presence and status of any co-existing diseases. Digestive problems Refer to the guidance found in Regulations You must review and discuss with the driver any "Yes" answers. Diabetes or elevated blood glucose controlled by diet, pills, or insulin Ask about treatment, whether by diet, oral medications, Byetta, or insulin. To do so, the medical examiner must complete the examination and check the following boxes: Meets standards but periodic monitoring required due to (write in: insulin treatment). Loss of or altered consciousness Loss of consciousness while driving endangers the driver and the public. Your discussion with the driver should include cause, duration, initial treatment, and any evidence of recurrence or prior episodes of loss of or altered consciousness. Health History (Column 3) Overview In addition to the guidance provided in the section above, directions specific to each category in Column 3 are listed below for each "Yes" answer. Fainting, dizziness Note whether the driver checked ?Yes? due to fainting or dizziness. Ask about episode characteristics, including frequency, factors leading to and surrounding an episode, and any associated neurologic symptoms. Sleep disorders, pauses in breathing while asleep, daytime sleepiness, loud snoring Ask the driver about sleep disorders. Also ask about such symptoms as daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, or pauses in breathing while asleep. Page 31 of 260 Stroke or paralysis Note any residual paresthesia, sensory deficit, or weakness as a result of stroke and consider both time and risk for seizure. Missing or impaired hand, arm, foot, leg, finger, toe Determine whether the missing limb affects driver power grasping, prehension, or ability to perform normal tasks, such as braking, clutching, accelerating, etc. Spinal injury or disease Refer to the guidance found in Regulations You must review and discuss with the driver any "Yes" answers. How does the pain affect the ability of the driver to perform driving and nondriving tasks? You should refer the driver who shows signs of a current alcoholic illness to a specialist. Health History Medical Examiner Comments Overview At a minimum, your comments should include: Include a copy of any supplementary medical reports obtained to complete the health history. Page 32 of 260 Vision the Medical Examiner completes section 3: Figure 7 Medical Examination Report Form: Vision Vision Medical Examiner Instructions To meet the Federal vision standard, the driver must meet the qualification requirements for vision with both eyes. Distant visual acuity of at least 20/40 (Snellen) in each eye, with or without corrective lenses. Use of contact lenses when one lens corrects distant visual acuity and the other lens corrects near visual acuity. Specialist Vision Certification the vision testing and certification may be completed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. When the vision test is done by an ophthalmologist or optometrist, that provider must fill in the date, name, telephone number, license number, and State of issue, and sign the examination form. Additionally, ensure that any attached specialist report includes all required examination and provider information listed on the Medical Examination Report form. Hearing the Medical Examiner completes section 4: Figure 8 Medical Examination Report Form: Hearing Hearing Medical Examiner Instructions To meet the Federal hearing standard, the driver must successfully complete one hearing test with one ear. If the driver uses a hearing aid while testing, mark the ?Check if hearing aid used for tests? box. Forced whisper test Record the distance, in feet, at which a whispered voice is first heard. By signing the Medical Examination Report form, you are taking responsibility for and attesting to the validity of all documented test results. Hearing Hearing Test Example In the example above, the examiner has documented the test results for both hearing tests. The forced whisper test was administered first, and hearing measured by the test failed to meet the minimum five feet requirement in both ears. Therefore, the medical examiner also administered an audiometric test, resulting in: The medical examiner may use his/her clinical expertise and results of the individual driver examination to determine the length of time between recertification examinations. Figure 10 Medical Examination Report Form: Blood Pressure/Pulse Rate Recommendation Table the following table corresponds to the first two columns of the recommendation table in the Medical Examination Report form. Column one has the blood pressure readings, and column two has the category classification. The next table corresponds to columns three and four of the recommendation table in the Medical Examination Report form. Use the Expiration Date and Recertification columns to assist you in determining driver certification decisions. Expiration Date Recertification 1 year 1 year if less than or equal to 140/90 1 year from date of examination if less than One-time certificate for 3 months or equal to 140/90 6 months from date of examination if less 6 months if less than or equal to 140/90 than or equal to 140/90 Table 3 Blood Pressure/Pulse Rate Recommendation Table Columns 3 and 4 A driver with Stage 3 hypertension (greater than or equal to 180/110) is at an unacceptable risk for an acute hypertensive event and should be disqualified. Urinalysis the Medical Examiner Completes section 6: Table 4 Medical Examination Report Form: Laboratory and Other Test Findings Laboratory and Other Test Findings Medical Examiner Instructions Regulations You must perform a urinalysis (dip stick) Test for: Additional Tests and/or Evaluation from a Specialist Abnormal dip stick readings may indicate a need for further testing. As a medical examiner, you should evaluate the test results and other physical findings to determine the next step. If the urinalysis, combined with other medical findings, indicates the potential for renal dysfunction, you should obtain additional tests and/or consultation to adequately assess driver medical fitness for duty. Attach any additional medical reports obtained to the Medical Examination Report form. Page 38 of 260 Physical Examination the Medical Examiner completes section 7: Figure 11 Medical Examination Report Form: Physical Evaluation Physical Examination Record Driver Height and Weight Regulations You must measure and record driver height (inches) and weight (pounds) the physical qualification standards do not include any maximum or minimum height and weight requirements. You should consider height and weight factors as part of the overall driver medical fitness for duty. Regulations You must perform the described physical examination the physical examination should be conducted carefully and must, at a minimum, be as thorough as the examination of body systems outlined in the Medical Examination Report form. For each body system, mark "Yes" if abnormalities are detected, or "No" if the body system is normal.

Buy generic promethazine online. ఫుడ్ ఎలర్జీ గురించి తప్పకుండా తెలుసుకోవాల్సిన విషయాలు..! Food Allergy Unknown Facts | Health Tips.