Kevin G Kerr BSc MBChB MD FRCPath

- Consultant microbiologist and Honorary

- Clinical Professor (Microbiology)

- Harrogate and District NHS Foundation

- Trust, Harrogate, UK

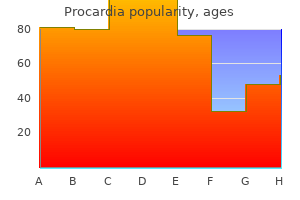

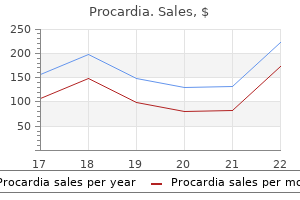

As a result cardiovascular disease epidemiology and prevention cheap procardia 30 mg with amex, the ing the 5-year-old sites resulted in a decrease in total losses in site productivity per unit N loss (ah to bh) from soil C and N and a decrease in the C/N ratio zap capillaries discount procardia 30 mg fast delivery. Total soil sites of high productivity (lh) are less than losses in site C and N in the surface soils did not respond to burning productivity per unit N loss (a to b) from sites havingi i on the 12-year-old site heart disease and nutrition purchase procardia visa. The amount of N lost is generally propor tional to the amount of organic matter combusted Phosphorus during the fire cardiovascular ultrasound tech jobs order discount procardia on-line. Deficiencies of (Christensen 1973 cardiovascular fitness level generic 30 mg procardia with amex, DeBano and others 1979 cardiovascular system arteries order procardia with visa, Carballas P have been reported in P-fixing soils (Vlamis and and others 1993). This increased N availability en others 1955) and as a result from N fertilization hances postfire plant growth, and gives the impres applications (Heilman and Gessel 1963). This uptake and availability to plants is complicated by the increase in fertility, however, is misleading and can be relationship between mycorrhizae and organic matter short-lived. Any temporary increase in available N and in most cases does not involve a simple absorption following fire is usually quickly utilized by plants from the soil solution (Trappe and Bollen 1979). In N-limited ecosystems even small large amount of highly available P in the surface ash losses of N by volatilization can impact long-term found on the soil surface immediately following fire productivity (fig. For ever, can be quickly immobilized if calcareous sub stances are present in the ash and thus can become unavailable for plant growth. Sulfur the role of S in ecosystem productivity is not well understood although its fluctuation in the soil is gen erally parallel to that of inorganic N (DeBano and others 1998). Sulfur has been reported as limiting in some coastal forest soils of the Pacific Northwest, particularly after forest stands have been fertilized with N (Barnett 1989). The loss of S by volatilization occurs at temperatures intermediate to that of N and P (Tiedemann 1987), and losses of 20 to 40 percent of the S in aboveground biomass have been reported during fires (Barnett 1989). In summary, many nutrients essential for plant growth including N, P, S, and some cations described earlier are all affected to some extent by fire. Nitrogen Soil Chemical Processes is likely the most limiting nutrient in natural systems (Maars and others 1983), followed by P and S. Cations Nutrient Cycling released by burning may affect soil pH and result in Nutrients undergo a series of changes and transfor the immobilization of P. The role of micronutrients in mations as they are cycled through wildland ecosys ecosystem productivity and their relationship to soil tems. The sustained productivity of natural ecosys heating during fire is for the most part unclear. One tems depends on a regular and consistent cycling of study, however, did show that over half of the sele nutrients that are essential for plant growth (DeBano nium in burned laboratory samples was recovered in and others 1998). Nutrients are added to the soil by precipitation, dry fall, N fixation, and the geochemical weathering Nutrient losses during and following fire mainly of rocks. The disposition of nutri transformed by decomposition and mineralization into ents contained in plant biomass and soil organic mat forms that are available to plants (see chapter 4). In ter during and following a fire generally occurs in one nonfire environments, nutrient availability is regu of the following ways: lated biologically by decomposition processes. Nitrogen can be ing on moisture, temperature, and type of organic transformed into N along with other nitrog 2 matter. Through the process of decomposi and cations are frequently lost into the atmo tion, this material breaks down, releases nutrients, sphere as particulate matter during combus and moves into the soil as soil organic matter. These highly available nutrients needed, rely on this internal cycling of nutrients to are vulnerable to postfire leaching into and maintain plant growth (Perala and Alban 1982). As a through the soil, or they can also be lost during result, nutrient losses from unburned ecosystems are wind erosion (Christensen 1973, Grier 1975, usually low, although some losses can occur by volatil Kauffman and others 1993). This pattern of tightly controlled nutrient cycling mini mizes the loss of nutrients from these wildland sys tems in the absence of any major disturbance such as fire. Fire, however, alters the nutrient cycling processes in wildland systems and dramatically replaces long term biological decomposition rates with that of in stantaneous thermal decomposition that occurs dur ing the combustion of organic fuels (St John and Rundel 1976). The magnitude of these fire-related changes depends largely on fire severity (DeBano and others 1998). For example, high severity fires occur ring during slash burning not only volatilize nutrients both in vegetation and from surface organic soil hori zons, but heat is transferred into the soil, which further affects natural biological processes such as decomposition and mineralization (fig. These losses are amplified forest floor organic matter to that of being highly by the creation of a water-repellent layer dur available as an inorganic form present in the ash layer ing the fire (see chapter 2; DeBano and Conrad after fire. Nutrients can remain onsite as part of come more available in the surface soil as a result of the incompletely combusted postfire vegeta fire. Everything ex effect can be measured to a greater depth due to the cept Zn and organic C increased in terms of total leaching or movement of the highly mobile nutrients nutrients. Raison on an area of pine forest burned by a wildfire reported and others (1990) noted that while K, Na, and Mg are that in the soil, concentrations of P, Ca, and Mg, relatively soluble and can leach into and possibly aluminum (Al), iron (Fe) had increased in response to through the soil, Ca is most likely retained on the different levels of fire severity (Groeschl and others cation exchange sites. In the areas exposed to a high-severity fire, C response in the surface soils for many years following and N were significantly lower and soil pH was greater. However, some cations more readily leached In another study the soil and plant composition changes and as a result are easily lost from the site. Phosphorus, K, Ca, and Mg all measured changes in the pattern of cation leaching at increased in the mineral soil; P and K were still greater differing temperatures for the six soils that repre than preburn levels 10 years later. Leaching pat ment fire in the Southern Appalachians that resulted terns were similar for all soil types. Leaching of diva in a mosaic burn pattern affected exchangeable ions lent cations, Ca, and Mg, increased as the temperatures (Vose and others 1999). Monovalent cations, K, and Na, exchangeable K and Mg along with an increase in soil differed in that initially leaching decreased as tem pH was measured. The nutrients leached from the forest floor soil nutrients following burning (Sands 1983, Carreira and the ash were adsorbed in the mineral soil. The instantaneous combustion of organic matter thermal decomposition of proteins and other nitrogen described earlier directly changes the availability of rich organic matter. These secondary amide are produced as a result of fire generally increase groups are particularly sensitive to decomposition with the severity and duration of the fire and the during heating and decompose when heated above 212 associated soil heating (fig. The ing fire and in the upper mineral soil layers (Groeschl ash produced by the fire can also contain substantial and others 1990, Covington and Sackett 1992). As a result of these two processes, the inorganic N in the soil increases during fire (Kovacic and others 1986, Raison and others 1990, Knoepp and Swank 1993a,b). These N03-N concentrations may remain elevated for sev eral years following fire (fig. These include fire severity, forest type, and the use of fire in combination with other postharvesting activities. Cations Increase ammonia-N pH Prefire Soil organic matter Decrease Total N Duff Low Moderate High Burn Severity Figure 3. Re high or low severity fires increased only slightly searchers concluded from this Arizona study that (Groeschl and others 1990). A more common scenario frequent periodic burning can be used to enhance N for N03-N changes following fire results from the availability in Southwestern ponderosa pine forests. For example, the annual burning during fire is rapidly nitrified, and N03-N begins to of tall grass prairies in the Great Plains of the Central increase following fire, depending on temperature and United States resulted in greater inputs of lower moisture conditions (fig. However, these short-term in available N may have adverse effects on some benefits must be carefully weighed against the overall nutrient-deficient shrub ecosystems as has been re and long-term effect that the loss of total N during a ported by a study in a shrubland (fynbos) in South fire has on the sustained productivity of the site (see Africa. Such was the case in a study conducted in those of other nutrients (Raison and others 1990). One study indicated that the only following burning of the pine/hemlock forest in con response was on the surface soil, and P did not appear trast to the Douglas-fir/western larch forest site where to move downward in the soil via volatilization and it did increase. Part of this depend upon the characteristics of the fuels that are volatilized P ends up as increased available P in both combusted, such as fuel densities (packing ratios), fuel the soil and ash following burning. An extensive study moisture content, total amount of the fuel load con of P responses to different burning severities was sumed, and severity of the fire (Gillon and others reported for eucalypt forests (Romanya and others 1995). The study sites included unburned, burned, a fire can range from small amounts of charred dark and in an ash bed found under a burned slash pile. The colored fuel residues to thick layers of white ash that greatest effects occurred in the surface soil (0-1 inch; are several centimeters thick (DeBano and others 0-2. Extractable P concentrations increased with combusted, large amounts of residual white ash are increasing fire severity, but the response decreased usually in one place on the soil surface following with depth. Organic P on the other hand reacted burning (such as after piling and burning slash, see oppositely; concentrations were lower in the inten Figure 1. The severe heating during the fire will sively burned areas and greater in the unburned and change the color of the soil mineral particles to a low-severity burned sites. Ash extractable P concentrations (ortho-phosphate) showed consists mostly of carbonates and oxides of metals and no significant response. In contrast, a wildfire that silica along with small amounts of P, S, and N (Raison produced higher soil temperatures reduced phos and others 1990). Calcium is usually the dominant phatase activity and increased the mineralization of cation found in these ash accumulations. Most of the organic P, which increased ortho-phosphate P and cations are leached into the soil where they are re decreased organic P. Laboratory experiments showed tained on the cation exchange sites located on clay or that phosphatase activity can be significantly reduced humus particles and increase the mineral soil cation when heating dry soils but was absent in wet soils content (fig. In the pinyon-juniper the composition of the preburn material and the tem soils being studied, bicarbonate extractable P was perature or severity of the fire determines the chemi increased although the increases were short lived. Johnston and Elliott (1998) found that ash on uncut forest plots generally had the highest pH and the lowest P concentrations. Ash-Bed Effect Physical changes associated with the ash bed effect Following fire, variable amounts of ash are left mainly include changes in soil structure and perme remaining on the soil surface until the ash is either ability to water. The combustion of organic matter in blown away or is leached into the soil by precipitation the upper part of the soil profile can totally destroy soil (fig. On severely burned sites, large layers of ash structure, and the ashy material produced often seals can be present (up to several centimeters thick). Ash deposits are usually greatest after the affect the long-term functioning of microbial popula burning of concentrated fuels (piled slash and wind tions because the high temperature essentially steril rows) and least following low-severity fires. Indirectly, the large Humphreys and Lambert 1965, Renbuss and others amounts of ash can affect soil microbial populations. The severe burning conditions necessary to study of the effects of ash, soil heating, and the ash create these thick beds of ash affect most of the heat interaction on soil respiration in two Australian physical, chemical, and biological soil properties. Many of these sterilized soil produced no effect, indicating that ash ecosystems are low in available N and other nutrients acted via its influence on active soil biological popula such as P and cations. The chemical nature of ash was hypothesized to cially N, may be slow, and the exclusion of fire from affect soil respiration by its effect on: these systems often results in low N mineralization and nitrification rates. These monoterpenes are highly flammable and as a result are combusted during a fire. As a result, the removal Management Implications of this inhibition by fire allows N mineralization and Understanding the effects of fire on soil chemical nitrification to proceed. It is hypothesized that these properties is important when managing fire on all inhibitory compounds build up over time after a fire ecosystems, and particularly in fire-dependent sys and decrease N mineralization. Fire and associated soil heating combusts or in monoterpenes concentrations have been established ganic matter and releases an abundant supply of between early and late successional stages, although highly soluble and available nutrients. The amount of specific changes over time have not been detectable change in the soil chemical properties is proportional because of the large variability between sites (White to the amount of the organic matter combusted on the 1996). Not Another study has shown that the xeric pine-hard only are nutrients released from organic matter dur wood sites in the Southern Appalachians are disap ing combustion, but there can also be a corresponding pearing because of past land use, drought, insects, and loss of the cation exchange capacity of the organic the lack of regeneration by the fire-dependent pine humus materials. This information was used to of the humus may be an important factor when burn develop an ecological model that could be used as a ing over coarse-textured sandy soils because only a forest management tool to rejuvenate these Pinus small exchange capacity of the remaining mineral rigida stands (fig. This model specifies that particles is available to capture the highly mobile a cycle of disturbance due to drought and insect cations released during the fire. Excessive leaching and loss can thus result, which may be detrimental to maintaining site fertility on nutrient-limiting sandy soil. An important chemical function of organic matter is its role in the cycling of nutrients, especially N. Nitro gen is most limiting in wildland ecosystems, and its losses by volatilization need to be evaluated before conducting prescribed burning programs. Xeric and pine dominated sites, which are typi cally prone to burning, often exhibit low N availability, with low inorganic N concentrations and low rates of potential mineralization measured on these sites (White 1996, Knoepp and Swank 1998). Forest distur bance, through natural or human-caused means, fre quently results in an increase of both soil inorganic N concentrations and rates of potential N mineralization and nitrification.

Stress continues to be one of the most important and well-studied psychological correlates of illness heart disease 40 years old order procardia 30 mg overnight delivery, because excessive stress causes potentially damaging wear and tear on the body and can influence almost any disease process cardiovascular assessment nursing buy procardia 30mg without prescription. Dispositions and Stress: Negative dispositions and personality traits have been strongly tied to an array of health risks cardiovascular disease quiz order procardia 30 mg line. One of the earliest negative trait-to-health connections was discovered in the 1950s by two cardiologists blood vessels structure buy procardia without prescription. They made the interesting discovery that there were common behavioral and psychological patterns among their heart patients that were not present in other patient samples braunwald heart disease 9th edition chm order cheap procardia line. Importantly coronary heart condition purchase procardia line, it was found to be associated with double the risk of heart disease as compared with Type B Behavior (absence of Type A behaviors) (Friedman & Rosenman, 1959). Since the 1950s, researchers have discovered that it is the hostility and competitiveness components of Type A that are especially harmful to heart health 340 (Iribarren et al. Hostile individuals are quick to get upset, and this angry arousal can damage the arteries of the heart. In addition, given their negative personality style, hostile people often lack a heath-protective supportive social network. In fact, the importance of social relationships for our health is so significant that some scientists believe our body has developed a physiological system that encourages us to seek out our relationships, especially in times of stress (Taylor et al. Social integration is the concept used to describe the number of social roles that you have (Cohen & Willis, 1985). For example, you might be a daughter, a basketball team member, a Humane Society volunteer, a coworker, and a student. Maintaining these different roles can improve your health via encouragement from those around you to maintain a healthy lifestyle. By helping to improve health behaviors and reduce stress, social relationships can have a powerful, protective impact on health, and in some cases, might even help people with serious illnesses stay alive longer (Spiegel, Kraemer, Bloom, & Gottheil, 1989). Caregiving and Stress: A disabled child, spouse, parent, or other family member is part of the lives of some midlife adults. According to the National Alliance for Caregiving (2015), 40 million Americans provide unpaid caregiving. The typical caregiver is a 49 year-old female currently caring for a 69 year-old female who needs care because of a long-term physical condition. Looking more closely at the age of the recipient of caregiving, the typical caregiver for those 18-49 years of age is a female (61%) caring mostly for her own child (32%) followed by a spouse or partner (17%). When looking at older recipients (50+) who receive care, the typical caregiver is female (60%) caring for a parent (47%) or spouse (10%). Caregiving for a young or adult child with special needs was associated with poorer global health and more physical symptoms among both fathers and mothers (Seltzer, Floyd, Song, Greenberg, & Hong, 2011). Marital relationships are also a factor in how the caring affects stress and chronic conditions. Fathers who were caregivers identified more chronic health conditions than non-caregiving fathers, regardless of marital quality. In contrast, caregiving mothers reported higher levels of chronic conditions when they reported a high level of marital strain (Kang & Marks, 2014). Age can also make a 341 difference in how one is affected by the stress of caring for a child with special needs. Using data from the Study of Midlife in the Unites States, Ha, Hong, Seltzer and Greenberg (2008) found that older parents were significantly less likely to experience the negative effects of having a disabled child than younger parents. Currently 25% of adult children, mainly baby boomers, provide personal or financial care to a parent (Metlife, 2011). Daughters are more likely to provide basic care and sons are more likely to provide financial assistance. Adult children 50+ who work and provide care to a parent are more likely to have fair or poor health when compared to those who do not provide care. Some adult children choose to leave the work force, however, the cost of leaving the work force early to care for a parent is high. For females, lost wages and social security benefits equals $324,044, while for men it equals $283,716 (Metlife, 2011). Consequently, there is a need for greater workplace flexibility for working caregivers. However, research indicates that there can be positive health effect for caring for a disabled spouse. Beach, Schulz, Yee and Jackson (2000) evaluated health related outcomes in four groups: Spouses with no caregiving needed (Group 1), living with a disabled spouse but not providing care (Group 2), living with a disabled spouse and providing care (Group 3), and helping a disabled spouse while reporting caregiver strain, including elevated levels of emotional and physical stress (Group 4). Not surprisingly, the participants in Group 4 were the least healthy and identified poorer perceived health, an increase in health-risk behaviors, and an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms. However, those in Group 3 who provided care for a spouse, but did not identify caregiver strain, actually identified decreased levels of anxiety and depression compared to Group 2 and were actually similar to those in Group 1. It appears that greater caregiving involvement was related to better mental health as long as the caregiving spouse did not feel strain. The beneficial effects of helping identified by the participants were consistent with previous research (Krause, Herzog, & Baker, 1992; Schulz et al. Female caregivers of a is associated with greater stress spouse with dementia experienced more burden, had poorer mental and physical health, exhibited increased depressive symptomatology, took part in fewer health promoting activities, and received fewer hours of help than male caregivers (Gibbons et al. This study was consistent with previous research findings that women experience more caregiving burden than men, despite similar caregiving situations (Torti, Gwyther, Reed, Friedman, & Schulman, 2004; Yeager, Hyer, Hobbs, & Coyne, 2010). Female caregivers are certainly at risk for negative consequences of caregiving, and greater support needs to be available to them. Stress Management: On a scale from 1 to 10, those Americans aged 39-52 rated their stress at 5. The most common sources of stress included the future of our nation, money, work, current political climate, and violence and crime. Given that these sources of our stress are often difficult to change, a number of interventions have been designed to help reduce the aversive responses to duress, especially related to health. For example, relaxation activities and forms of meditation are techniques that allow individuals to reduce their stress via breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and mental imagery. Physiological arousal from stress can also be reduced via biofeedback, a technique where the individual is shown bodily information that is not normally available to them. This type of intervention has even shown promise in reducing heart and hypertension risk, as well as other serious conditions (Moravec, 2008; Patel, Marmot, & Terry, 1981). For example, exercise is a great stress reduction activity (Salmon, 2001) that has a myriad of health benefits. Problem-focused coping is thought of as actively addressing the event that is causing stress in an effort to solve the issue at hand. A problem-focused strategy might be to spend additional time over the weekend studying to make sure you understand all of the material. Emotion-focused coping, on the other hand, regulates the emotions that come with stress. In the above examination example, this Source might mean watching a funny movie to take your mind off the anxiety you are feeling. In the short term, emotion-focused coping might reduce feelings of stress, but problem-focused coping seems to have the greatest impact on mental wellness (Billings & Moos, 1981; Herman-Stabl, Stemmler, & Petersen, 1995). Therefore, it is always important to consider the match of the stressor to the coping strategy when evaluating its plausible benefits. This stage includes the generation of new beings, new products, and new ideas, as well as self-generation concerned with further identity development. Erikson believed that the stage of generativity, during which one established a family and career, was the longest of all the stages. Individuals at midlife are primarily concerned with leaving a positive legacy of themselves, and parenthood is the primary generative type. Erikson understood that work and family relationships may be in conflict due to the obligations and responsibilities of each, but he believed it was overall a positive developmental time. In addition to being parents and working, Erikson also described individuals being involved in the community during this stage. A sense of stagnation occurs when one is not active in generative matters, however, stagnation can motive a person to redirect energies into more meaningful activities. Further, Erikson believed that the strengths gained from the six earlier stages are essential for the generational task of cultivating strength in the next generation. Erikson further argued that generativity occurred best after the individual had resolved issues of identity and intimacy (Peterson & Duncan, 2007). Using the Big 5 personality traits, generative women and men scored high on conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and low on neuroticism (de St. Additionally, women scoring high in generativity at age 52, were rated high in positive personality characteristics, satisfaction with marriage and Source motherhood, and successful aging at age 62 (Peterson & Duncan, 2007). Similarly, men rated higher in generativity at midlife were associated with stronger global cognitive functioning. Erikson (1982) indicated that at the end of this demanding stage, individuals may withdraw as generativity is no longer expected in late adulthood. In addition, 15% of middle-aged adults are providing financial support to an older parent while raising or supporting their own children (see Figure 8. According to the same survey, almost half (48%) of middle-aged adults, have supported their adult children in the past year, and 27% are the primary source of support for their grown children. Seventy-one percent of the sandwich generation is age 40-59, 19% were younger than 40, and 10% were 60 or older. Hispanics are more likely to find themselves supporting two generations; 31% have parents 65 or older and a dependent child, compared with 24% of whites and 21% of blacks (Parker & Patten, 2013). Women are more likely to take on the role of care provider for older parents in the U. About 20% of women say they have helped with personal care, such as getting dressed or bathing, of aging parents in the past year, compared with 8% of men in the U. In contrast, in Italy men are just as likely (25%) as women (26%) to have provided personal care. However, the survey suggests that those who were supporting both parents and children reported being just as happy as those middle-aged adults who did not find themselves in the sandwich generation (Parker & Patten, 2013). Adults who are supporting both parents and children did report greater financial strain (see Figure 8. Only 28% reported that they were living comfortably versus 41% of those who were not also supporting their parents. Almost 33% were just making ends meet, compared with 17% of those who did not have the additional financial burden of aging parents. In all families there is a person or persons who keep the family connected and who promote solidarity and continuity in the family (Brown & DeRycke, 2010). Brown and DeRycke also found that among young adults, women were more likely to be a kinkeeper than were young adult men. Kinkeeping can be a source of distress when it interferes with other obligations (Gerstel & Gallagher, 1993). Gerstel and Gallagher found that on average, kinkeepers provide almost a full week of work each month to kinkeeping (almost 34 hours). They also found that the more activities the kinkeeper took on, and the more kin they helped the more stress and higher the levels of depression a kinkeeper experienced. Empty nest: the empty nest, or post-parental period refers to the time period when children are grown up and have left home (Dennerstein, Dudley & Guthrie, 2002). The empty nest creates complex emotions, both positive and negative, for many parents. Some theorists suggest this is a time of role loss for parents, others suggest it is one of role strain relief (Bouchard, 2013). The role loss hypothesis predicts that when people lose an important role in their life they experience a decrease in emotional well-being. It is from this perspective that the concept of the empty nest syndrome emerged, which refers to great emotional distress experienced by parents, typically mothers, after children have left home. The empty nest syndrome is linked to the absence of alternative roles for the parent in which they could establish their identity (Borland, 1982). In contrast, the role stress relief hypothesis suggests that the empty nest period should lead to more positive changes for parents, as the responsibility of raising children has been lifted.

The prevalence estimates of birth defects were compatible with the background number of congenital anomalies expected in the general population 4 types of arteries order 30 mg procardia visa. Reporting of instances of inadvertent immunization with a varicella/zoster virus-containing vaccine during pregnancy by telephone is encouraged (1-800-986-8999) heart disease in the us generic 30mg procardia. Transmission of vaccine virus from an immunocompetent vaccine recipient to a susceptible person has been reported only rarely coronary heart logo buy procardia online, and only when a vaccine-associated rash develops in the vaccinee (see Varicella Zoster Infections arteries in hand order procardia 30 mg overnight delivery, p 774) capillaries quiz order procardia without prescription. If Varicella-Zoster Immune Globulin is not available heart disease xanax cheap 30 mg procardia overnight delivery, some experts suggest use of Immune Globulin Intravenous; use of acyclovir in this circumstance has not been evaluated. Pregnant women at risk of exposure to unusual pathogens should be considered for immunization when the potential benefts outweigh the potential risks to the mother and fetus. It should not be administered to pregnant women, and pregnancy should be avoided for 3 months following a dose. Initiation of the vaccine series should be delayed until after completion of the pregnancy. If a woman is found to be pregnant after initiating the immunization series, the remainder of the 3-dose regimen should be delayed until after completion of the pregnancy. If a vaccine dose has been administered during pregnancy, no intervention is needed. Because smallpox causes more severe disease in pregnant than nonpregnant women, the potential risks of immunization may be outweighed by the risk of disease. Immunized household contacts should avoid contact with pregnant women until the vaccination site is healed. Immunocompromised people vary in their degree of immunosuppression and susceptibility to infection and represent a het erogeneous population with regard to immunization. Published studies of experience with vaccine administration to immunocompromised children are limited. There are particular immune defciency disorders with which some live vaccines are safe, and for certain immunocom promised children and adolescents, the benefts may outweigh risks for use of particular live vaccines. All children 6 months of age and older and adolescents with primary and secondary immuno defciencies should receive an annual age-appropriate inactivated infuenza vaccine to prevent infuenza and secondary bacterial infections associated with infuenza disease. In children with secondary immunodefciency, the ability to develop an adequate immunologic response depends on the presence of immunosuppression during or within 2 weeks of immuniza tion. Specifc immune globulins are available for postexposure prophylaxis for some infections (see Specifc Immune Globulins, p 59). Children with milder B-lymphocyte and antibody def ciencies have an intermediate degree of vaccine responsiveness and may require monitor ing of postimmunization antibody concentrations to confrm responses to vaccination. Because these vaccines are recommended for infants 1 beginning at 6 weeks of age, some recipients will have these as-yet undiagnosed diseases and have the potential for prolonged shedding and illness. The potential risks should be weighed against the benefts of administering rotavirus vaccine to infants with known or suspected altered immunocompetence (see Rotavirus, p 626). In addition, children with early complement defciencies should receive pneumococcal vaccine (including pneumococcal polysac charide vaccine) and meningococcal conjugate vaccine (see Pneumococcal Infections, p 571, and Meningococcal Infections, p 500, for specifc details). Children with late comple ment defciencies should receive meningococcal conjugate vaccine starting at 9 months of age. Several factors should be considered in immunization of children with secondary immunodefciencies, including the underly ing disease, the specifc immunosuppressive regimen (dose and schedule), and the infec tious disease and immunization history of the person. Addition of severe combined immunodefciency as a contra indication for administration of rotavirus vaccine. Although varicella vaccine has 1 been studied in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission, varicella vac cine generally should not be given to children with acute lymphocytic leukemia or another malignancy, because (a) many children will have received varicella vaccine prior to immune suppression and may retain protective immunity; (b) the risk of acquiring varicella has diminished in some countries with universal immunization programs; (c) antiviral agents are available for treatment; and (d) chemotherapy regimens change fre quently and often are more immunosuppressive than regimens under which the safety and effcacy of varicella vaccine was studied (see Varicella-Zoster Infections, p 774). For corticosteroid therapy (see Corticosteroids, p 81), the interval is based on the assumption that immune response will have been restored in 3 months and that the underlying disease for which immunosuppressive therapy was given is in remission or under control. The interval until immune reconstitution varies with the inten sity and type of immunosuppressive therapy, radiation therapy, underlying disease, and other factors. Therefore, often it is not possible to make a defnitive recommendation for an interval after cessation of immunosuppressive therapy when live-virus vaccines can be administered safely and effectively. Because patients with congenital or acquired immunodefciencies may not have an adequate response to vaccines, they may remain susceptible despite having been immunized. If there is an available test for a known antibody correlate of protection, specifc postimmunization serum antibody titers can be determined 4 to 6 weeks after immunization to assess immune response and guide further immunization and management of future exposures. In such instances, the vaccine recipient should avoid direct contact with 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The minimal amount of systemic corticosteroids and duration of administration suf fcient to cause immunosuppression in an otherwise healthy child are not well defned. The frequency and route of administration of corticosteroids, the underlying disease, and concurrent therapies are additional factors affecting immunosuppression. A dosage equivalent to 2 mg/kg per day of prednisone or equivalent to a total of 20 mg/day for children who weigh more than 10 kg, particularly when given for more than 14 days, is considered suffcient to raise concern about the safety of immu nization with attenuated live-virus vaccines. However, attenuated live-virus vaccines should not be administered if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of systemic immunosuppression until corticosteroid therapy has been discontinued for at least 1 month. Children who are receiv ing only maintenance physiologic doses of corticosteroids can receive attenuated live-virus vaccines. Children receiving 2 mg/kg per day of prednisone or its equiv alent, or 20 mg/day if they weigh more than 10 kg, can receive attenuated live-virus vaccines immediately after discontinuation of treatment. Children receiving 2 mg/kg per day of prednisone or its equiva lent, or 20 mg/day if they weigh more than 10 kg for 14 days or more, should not receive attenuated live-virus vaccines until corticosteroid therapy has been discontinued for at least 1 month. These children should not be given attenuated live-virus vaccines, except in special circumstances. When deciding whether to administer attenuated live-virus vaccines, the potential benefts and risks of immunization for an individual patient and the specifc circumstances should be considered. Their purpose is to block the action of cytokines involved in infammation, resulting in inhibition of the normal infammatory processes involved in the immune response. Patients treated with biologic response modifers are at risk of infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, molds and endemic fungi, Legionella species, Listeria species, and other intracellular pathogens as well as lymphomas and other cancers. The Canadian Paediatric Society has developed guidelines on preventive strategies that should be considered in patients who will be or who are taking these immune-modifying agents (Table 1. In theory, these results could be expected with other inactivated vaccine antigens. People with tetanus-prone wounds sustained during the frst year after transplantation should be given Tetanus Immune Globulin, regardless of their tetanus immunization status. Guidelines for preventing infec tious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Susceptible people who are exposed to measles should receive passive immunoprophylaxis (see Measles, p 489). Administration of inactivated infuenza vaccine annually is recommended starting at 4 to 6 months after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using an age appropriate schedule. Even in patients in whom there is no serologic response, T-lymphocyte responses may be elicited that may prevent serious disease. If the vaccine is given during the 6 months after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a second dose can be admin istered 4 or more weeks later. Live-virus vaccines should be given at least 1 month before transplantation and, in general, should not be given to patients receiving immunosuppressive medications after transplantation. For transplantation candidates who are older than 12 months of age, if previously immunized, serum con centrations of antibody to measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella should be measured. Most experts recommend waiting at least 6 months after transplantation, when immune suppression is less intense, for resumption of immunization schedules. Hepatitis A vaccine should be administered to patients undergoing liver trans plantation because of increased disease severity associated with hepatitis A infection in patients with chronic liver disease. Live-attenuated infu enza vaccine is contraindicated for solid organ transplant recipients because of immu nosuppressive therapy. Solid organ transplant recipients at highest risk of infection with S pneumoniae appear to be those who have undergone cardiac transplantation or splenec tomy. Pneumococcal conjugate and polysaccharide vaccine should be considered in all transplant recipients (see Pneumococcal Infections, p 571). Vaccine recipients who develop a rash should avoid direct contact with susceptible immunocompromised hosts for the duration of the rash. The risk of bacteremia is higher in younger children than in older children, and risk may be greater during the years imme diately after splenectomy. Fulminant septicemia, however, has been reported in adults as long as 25 years after splenectomy. Less common causes of bacteremia include H infuenzae type b, N meningitidis, other streptococci, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and gram-negative bacilli, such as Salmonella species, Klebsiella species, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A sec ond dose should be administered 5 years later (see Pneumococcal Infections, p 571). Hib immunization should be initiated at 2 months of age, as recommended for otherwise healthy young children (see Fig 1. Two primary doses of quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine should be administered 2 months apart to children with asplenia from 2 years of age through ado lescence, and a booster dose should be administered every 5 years (see Meningococcal 1 Infections, p 500), although the effcacy of meningococcal vaccines in children with asplenia has not been established. No known contraindication exists to giving these vaccines at the same time as other required vaccines in separate syringes at different sites. Daily antimicrobial prophylaxis against pneumococcal infections is recommended for many children with asplenia, regardless of immunization status. Although the effcacy of antimicrobial prophylaxis has been proven only in patients with sickle cell anemia, other children with asplenia at particularly high risk, such as children with malignant neoplasms or thalassemia, also should receive daily chemoprophylaxis. In general, antimicrobial prophylaxis (in addition to immunization) should be considered for all children with asplenia younger than 5 years of age and for at least 1 year after splenectomy. On the basis of a multicenter study, prophylactic penicillin can be discontinued at 5 years of age in children with sickle cell disease who are receiving regular medical attention and who have not had a severe pneumococcal infection or surgical splenectomy. The appro priate duration of prophylaxis for children with asplenia attributable to other causes is unknown. Some experts continue prophylaxis throughout childhood and into adulthood for particularly high-risk patients with asplenia. For children with anaphylactic allergy to penicillin, erythromycin can be given (250 mg, twice daily). Ongoing surveillance for resistant pneumococci is needed to determine whether changes to the recommended chemoprophylaxis will be required. When antimicrobial prophylaxis is used, the limitations must be stressed to parents and patients, who should recognize that some bacteria capable of causing fulminant septicemia are not susceptible to the antimicrobial agents given for prophylaxis. Parents should be aware that all febrile illnesses potentially are serious in children with asplenia and that immediate medical attention should be sought, because the initial signs and symptoms of fulminant septicemia can be subtle. In some clinical situations, other antimicrobial agents, such as aminoglycosides, may be indicated. If splenectomy is emergent, administration of indicated vaccines is recommended 2 weeks after surgery. Seizures following immunizations are brief, self-limited, and generalized and occur in conjunction with fever, indicating that such vaccine-associated seizures usually are febrile seizures. In contrast, measles and varicella immunization is given at an age when the cause and nature of any seizures and related neurologic status are more likely to have been established. A family history of a seizure disorder is not a contraindication to pertussis, measles, or varicella immunization or a reason to defer immunization. Children With Chronic Diseases Chronic diseases may make children more susceptible to the severe manifestations and complications of common infections. For children with conditions that may require organ transplantation or immunosuppression, administering recommended immunizations before the start of immunosuppressive therapy is impor tant. Children with certain chronic diseases (eg, cardiorespiratory, allergic, hematologic, metabolic, and renal disorders; cystic fbrosis; and diabetes mellitus) are at increased risk of complications of infuenza, varicella, and pneumococcal infection and should receive inactivated infuenza vaccine, live-varicella vaccine, and pneumococcal conjugate or polysaccharide vaccine as recommended for age and immunization status and condi tion (see Infuenza, p 439, Varicella-Zoster Infections, p 774, and Pneumococcal Infections, p 571). Susceptible (ie, lack of antibody, lack of a reliable history of varicella, or receipt of fewer than 2 doses of varicella-virus containing vaccine after 12 months of age) immunocompetent children 12 months of age or older and household con tacts exposed to a person with varicella disease should be given varicella vaccine within 72 hours of the appearance of the rash in the index case (see Varicella-Zoster Infections, p 774). For percutaneous or mucosal exposure to hepatitis B virus, combined active and passive immunization is recommended for susceptible people (see Hepatitis B, p 369). Thorough local cleansing and debridement of the wound and postexposure active and passive immunization are essential aspects of immunoprophylaxis for rabies after proven or suspected exposure to rabid animals (see Rabies, p 600). Administration of live-virus vaccine is recommended for adults born in the United States in 1957 or after who previously have not been immunized against or had mumps or rubella. Additionally, one quarter of rural Alaska Native communities lack in-home running water and fush toilets, and this lack of availability of water service is associated with increased risk of hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infections. Availability of more than 1 Hib vaccine in a clinic has been shown to lead to errors in the vaccine administration. Maternal immunization can provide protection of young infants who are at high risk of infuenza and complications. Children in Residential Institutions Children housed in institutions pose special problems for control of certain infectious diseases. All children entering a residential institution should have received recommended immunizations for their age (see Fig 1. Staff members should be familiar with standard precautions and procedures for handling blood and body fuids that might be contaminated by blood. For residents who acquire potentially transmis sible infectious agents while living in an institution, isolation precautions similar to those recommended for hospitalized patients should be followed (see Infection Control for Hospitalized Children, p 160). Hazards are disruption of activities, the need for acute nursing care in diffcult settings, and occasional serious complications (eg, in susceptible adult staff). If mumps is introduced, prophylaxis is not available to limit the spread or to attenuate the disease in a susceptible person. Infuenza can be unusually severe in a residential or custodial institutional setting. Current measures for control of infuenza in institutions include: (1) a program of annual infuenza immunization of residents and staff; (2) appropriate use of chemo prophylaxis during infuenza epidemics; and (3) initiation of an appropriate infection control policy (see Infuenza, p 439). Because progressive neurologic disorders may have resulted in a deferral of pertussis immunization, many children in an institutional setting may not be immu nized appropriately against pertussis. If pertussis is recognized, infected people and their close contacts should receive chemoprophylaxis (see Pertussis, p 553). Infection usually is mild or asymp tomatic in young children but can be severe in adults.

Order 30mg procardia with visa. Cardiovascular | Cardiac Cycle.