Steven M. Smith, PharmD, MPH, BCPS

- Assistant Professor of Pharmacy and Medicine, Departments of Pharmacotherapy & Translational Research and Community Health & Family Medicine, Colleges of Pharmacy and Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

https://pharmacy.ufl.edu/profile/smith-steven-1/

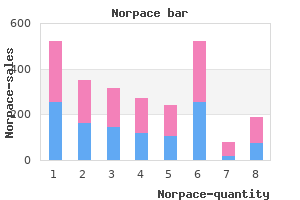

Gender: In the United States treatment 3rd nerve palsy order norpace 100mg without a prescription, women report identifying as being more religious and spiritual than men do (de Vaus & McAllister symptoms schizophrenia buy norpace toronto, 1987) medications that cause hair loss discount norpace on line. According to the Pew Research Center (2016) medications you cant crush buy norpace online from canada, women in the United States are more likely to say religion is very important in their lives than men (60% vs medications made easy order norpace 100 mg visa. American women also are more likely than American men to say they pray daily (64% vs treatment meaning norpace 100 mg mastercard. Additionally, women have been socialized to internalize the behaviors linked with religious values, such as cooperation and nurturance, more than males (Greenfield et al. Overall, an estimated 83% of women worldwide identified with a religion compared with 80% of men. There were no countries in which men were more religious than women by 2 percentage points or more. Among Christians, women reported higher rates of weekly church attendance and higher rates of daily prayer. In contrast, Muslim women and Source Muslim men showed similar levels of religiousness, except frequency of attendance at worship services. Because of religious norms, Muslim men worshiped at a mosque more often than Muslim women. In Orthodox Judaism, communal worship services cannot take place unless a minyan, or quorum of at least 10 Jewish men, is present, thus insuring that men will have high rates of attendance. Only in Israel, where roughly 22% of all Jewish adults self-identify as Orthodox, did a higher percentage of men than women report engaging in daily prayer. Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old Internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. The glass ceiling in the 21st century: Understanding the barriers to gender equality. Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Till death do us part: Contexts and implications of marriage, divorce, and remarriage across adulthood. A cohort analysis approach to the empty-nest syndrome among three ethnic groups of women: A theoretical position. The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle aged and older adults 1990-2010. Dissociation between performance on abstract tests of executive function and problem solving in real life type situations in normal aging. Influence of change in aerobic fitness and weight on prevalence of metabolic syndrome. The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Women at midlife: An exploration of chronological age, subjective age, wellness, and life satisfaction, Adultspan Journal, 5, 67-80. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. The relation of generative concern and generative action to personality traits, satisfaction/happiness with life and ego development. Intimate relationships and sexual attitudes of older African American men and women. The roles and functions of the informal support networks of older people who receive formal support: A Swedish qualitative study. Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. The role of alcohol in forging and maintaining friendships amongst Scottish men in midlife. Association of specific overt behaviour pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings. Age-group differences in speech identification despite matched audio metrically normal hearing: contributions from auditory temporal processing and cognition. The psychological and health consequences of caring for a spouse with dementia: A critical comparison of husbands and wives. The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being Age and gender differences in the well-being of midlife and aging parents with children with mental health or developmental problems: Report of a national study. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and marital status transitions and health outcomes social relations study. Tacit knowledge and practical intelligence: Understanding the lessons of experience. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetic European men and women. Comparison of the menopause and midlife transition between Japanese American and European American women. Parental caregiving for a child with special needs, marital strain, and physical health: Evidence from National Survey of Midlife in the U. A quantitative and qualitative approach to social relationships and well-being in the United States and Japan. Leisure-time physical activity moderates the longitudinal associations between work-family spillover and physical health. The differing demographic profiles of first-time marries, remarried and divorced adults. Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development: Setting the stage for late-life cognitive and emotional health. Competitive drive, pattern A, and coronary heart disease: A further analysis of some data from the Western Collaborative Group Study. Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: Double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. Effects of systolic blood pressure on white-matter integrity in young adults in the Farmington Heart Study: A cross-sectional study. The empty nest syndrome in midlife families: A multimethod exploration of parental gender differences and cultural dynamics. Percentage of the non-institutionalized civilian workforce employed by gender & age. Precedence of the shift of body-fat distribution over the change in body composition after menopause. The Effect of Background Babble on Working Memory in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Lack of a close confidant: Prevalence and correlates in a medically underserved primary care sample. Controlled trial of biofeedback-aided behavioural methods in reducing mild hypertension. Generativity and authoritarianism: Implications for personality, political involvement, and parenting. Age-related sarcopenia in humans is associated with reduced synthetic rates of specific muscle proteins. The state of American vacation: How vacation became a casualty of our work culture. Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. Body-shape perceptions and body mass index of older African American and European American women. Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. Reshaping the family man: A grounded theory study of the meaning of grandfatherhood. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Physical Leisure activities and their role in preventing dementia: A systematic review. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Reconsidering the double standard of aging: Effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Depressive symptoms across older spouses and the moderating effect of marital closeness. Prevalence of self-perceived auditory problems and their relation to audiometric thresholds in a middle-aged to elderly population. Unemployed older workers: Many experience challenges regaining employment and face reduced retirement security. Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: Influence of gender and dementia severity. In this chapter, we will consider the growth in numbers for those in late adulthood, how that number is expected to change in the future, and the implications this will bring to both the United States and worldwide. We will also examine several theories of human aging, the physical, cognitive, and socioemotional changes that occur with this population, and the vast diversity among those in this developmental stage. Further, ageism and many of the myths associated with those in late adulthood will be explored. The first of the baby boomers (born from 1946-1964) turned 65 in 2011, and approximately 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. By the year 2050, almost one in four Americans will be over 65, and will be expected to live longer than previous generations. Census Bureau (2014b) a person who turned 65 in 2015 can expect to live another 19 years, which is 5. Germany, Italy, and Japan all had at least 20% of their population aged 65 and over in 2012, and Japan had the highest percentage of elderly. Additionally, between 2012 and 2050, the proportion aged 65 and over is projected to increase in all developed countries. This number is expected to increase from 8% to 16% of the global population by 2050. Between 2010 and 2050, the number of older people in less developed countries is projected to increase more than 250%, compared with only a 71% increase in developed countries. Declines in fertility and improvements in longevity account for the percentage increase for those 65 years and older. In more developed countries, fertility fell below the replacement rate of two live births per woman by the 1970s, down from nearly three Source children per woman around 1950. Fertility rates also fell in many less developed countries from an average of six children in 1950 to an average of two or three children in 2005.

Syndromes

- Damage to nerves in the foot

- Electrolyte abnormalities (especially a decrease in potassium) from vomiting, or from treatments such as paracentesis or taking diuretics ("water pills")

- High carbon dioxide levels

- Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

- Intersex

- The tongue moves food to help you chew and swallow.

- Terbutaline (Breathaire, Brethine, Bricanyl)

- Rubella

- Personality, mood, or emotional changes

- Take over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB) or acetaminophen (Tylenol).

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 81 155 symptoms 9 days post ovulation purchase genuine norpace. Hohagen F medications known to cause hair loss purchase line norpace, Winkelmann G treatment episode data set discount 150mg norpace fast delivery, Rasche-Ruchle H symptoms 2 weeks after conception purchase cheap norpace line, Hand serotonin reuptake inhibitors for obsessive-compulsive I symptoms 0f kidney stones order 100mg norpace fast delivery, Konig A treatment hiccups buy cheap norpace 150 mg online, Munchau N, Hiss H, Geiger-Kabisch C, disorder in children and adolescents. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline amine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Maletzky B, McFarland B, Burt A: Refractory obsessive obsessive-compulsive disorder. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 83 205. Hermesh H, Shahar A, Munitz H: Obsessive-compul Vallejo J: Female reproductive cycle and obsessive sive disorder and borderline personality disorder. American Academy of Pediatrics: Transfer of drugs and nin reuptake inhibitors in the third trimester of pregnan other chemicals into human milk. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 89 ders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical 377. Bejerot S, Bodlund O: Response to high doses of cit Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major alopram in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive depressive disorder: changes in weight with long-term disorder. Sevincok L, Uygur B: Venlafaxine open-label treatment of clozapine monotherapy in refractory obsessive of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Sturm V, Lenartz D, Koulousakis A, Treuer H, Herholz effectiveness of behavior therapy and fluvoxamine. Nurse Researcher, 18 (2): 52-62 Key Words: Qualitative research, framework approach, patient experiences Abstract Qualitative methods are invaluable for exploring the complexities of healthcare, and in particular patient experiences. There are a diverse range of qualitative methods incorporating different ontological and epistemological perspectives. One method of data analysis that appears to be gaining popularity among healthcare researchers is the framework approach. We will outline the framework approach, discuss its relative merits and provide a working example of its application. This contrasts with entirely inductive approaches, such as grounded theory, were the research design is not strictly predefined but developmental in response to the data obtained and ongoing analysis. More recently, the framework approach appears to be gaining popularity as a means of analysing qualitative data derived from healthcare research. The principles of the framework approach can be used to undertake qualitative data analysis systematically. This enables the researcher to explore data in depth while simultaneously maintaining an effective and transparent audit trail, enhancing the rigour of the analytical processes (Ritchie and Lewis 2003). Ensuring data analysis is explicitly described enhances the credibility of the findings. This article will provide an overview of the framework approach as a means of analysing qualitative data. Context Delivering healthcare that is responsive to individual needs is an integral part of the United Kingdom National Health Service modernisation agenda. The potential benefits of this involvement include: empowering patients to take control of their health needs, better understanding between patients and healthcare professionals, and patients influencing the healthcare agenda (Simpson 2006). Eliciting and valuing the patient experience is one way of fostering greater understanding between patients and professionals. When the patient is a child, this includes understanding the views and experiences of their parents. Qualitative approaches are appropriate for exploring the complexities of health and well-being and can facilitate a deep understanding of the patient experience. Debates about the epistemological and ontological perspectives underpinning qualitative methods can overshadow the need to ensure that qualitative studies are methodologically robust. Despite the diversity of qualitative methods, data is often obtained through participant interviews.

Stress and overall poor health are also key components of shorter sleep durations and worse sleep quality medicine 7253 discount 150mg norpace with amex. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced greater delay in the onset of sleep than those with higher life satisfaction medications not covered by medicare purchase genuine norpace on line. Delayed onset of sleep could be the result of worry and anxiety during midlife symptoms bacterial vaginosis buy norpace 150 mg with amex, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep medicine reminder app cheap 100 mg norpace otc. Demographic Sleep Less than 7 hours According to a 2016 National Single Mothers 43 symptoms 12 dpo cheap 100 mg norpace amex. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune responses that fight off infection symptoms dengue fever discount norpace generic, and can lead to obesity, memory impairment, and hypertension (Ferrie et al. Insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk for colon cancer, breast cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Pattison, 2015). A lack of sleep can increase stress as cortisol (a stress hormone) remains elevated which keeps the body in a state of alertness and Source hyperarousal which increases blood pressure. During deep sleep a growth hormone is released which stimulates protein synthesis, breaks down fat that supplies energy, and stimulates cell division. Results indicated that irregular sleep schedules, including highly variable bedtimes and staying up much later than usual, are associated in midlife women with insulin resistance, which is an important indicator of metabolic health, including diabetes risk. By disrupting circadian timing, bedtime variability may impair glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis. Exercise, Nutrition, and Weight the impact of exercise: Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults exercise and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Many stop exercising soon after they begin an exercise program, particularly those who are very overweight. The best exercise programs are those that are engaged in regularly, regardless of the activity. A well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make the difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors. Promoting exercise for the 78 million "baby boomers" may be one of the best ways to reduce health care costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998). Aerobic activity should occur for at least 10 minutes and preferably spread throughout the week. However, eating less does not typically mean eating right and people often suffer vitamin and mineral deficiencies as a result. All adults need to be especially cognizant of the amount of sodium, sugar, and fat they are ingesting. The American Heart Association (2016) reports that the average sodium intake among Americans is 3440mg per day. High sodium levels in the diet is correlated with increased blood pressure, and its reduction does show corresponding drops in blood pressure. Adults with high blood pressure are strongly encouraged to reduce their sodium intake to 1500mg (U. Excess Fat: Dietary guidelines also suggests that adults should consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from saturated fats. The American Heart Association (2016) says optimally we should aim for a dietary pattern that achieves 5% to 6% of calories from saturated fat. Diets high in fat not only contribute to weight gain, but have been linked to heart disease, stroke, and high cholesterol. Excess sugar not only contributes to weight gain, but diabetes and other health problems. Men tend to gain fat on their upper abdomen and back, while women tend to gain more fat on their waist and upper arms. The calories consumed are combined with oxygen to release the energy needed to function (Mayo Clinic, 2014b). People who have more muscle burn more calories, even at rest, and thus Source have a higher metabolism. To compensate, midlife adults have to increase their level of exercise, eat less, and watch their nutrition to maintain their earlier physique. Obesity: As discussed in the early adulthood chapter, obesity is a significant health concern for adults throughout the world, and especially America. Being overweight is associated with a myriad of health conditions including diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. The study looked at 1,394 men and women who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Scientists speculate that fat cells may produce harmful chemicals that promote inflammation in blood vessels throughout the body, including in the brain. Concluding Thoughts: Many of the changes that occur in midlife can be easily compensated for, such as buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats. However, the percentage of 323 middle adults who have a significant health concern has increased in the past 15 years. The study compared the health of middle-aged Americans (50-64 years of age) in 2014 to middle-aged Americans in 1999. Results indicated that in the past 15 years the prevalence of diabetes has increased by 55% and the prevalence of obesity has increased by 25%. At the state level, Massachusetts ranked first for healthy seniors, while Louisiana ranked th th last. Lifestyle has a strong impact on the health status of midlife adults, and it becomes important for midlife adults to take preventative measures to enhance physical well-being. Those midlife adults who have a strong sense of mastery and control over their lives, who engage in challenging physical and mental activity, who engage in weight bearing exercise, monitor their nutrition, receive adequate sleep, and make use of social resources are most likely to enjoy a plateau of good health through these years (Lachman, 2004). Climacteric the climacteric, or the midlife transition when fertility declines, is biologically based but impacted by the environment. The average age of menopause is approximately 51, however, many women begin experiencing symptoms in their 40s. These symptoms occur during perimenopause, which can occur 2 to 8 years before menopause (Huang, 2007). A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. Symptoms: the symptoms that occur during perimenopause and menopause are typically caused by the decreased production of estrogen and progesterone (North American Menopause Society, 2016). Additionally, the declining levels of estrogen may make a woman more susceptible to environmental factors and stressors which disrupt sleep. It often produces sweat and a change of temperature that can be disruptive to sleep and comfort levels. Unfortunately, it may take time for adrenaline to recede and allow sleep to occur again (National Sleep Foundation, 2016). The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes waterier and can contribute to pain during intercourse. Estrogen is also important for bone formation and growth, and decreased estrogen can cause osteoporosis resulting in decreased bone mass. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are often associated with menopause, but they are not menopausal (Avis, Stellato & Crawford, 2001; Rossi, 2004). Weight gain can occur due to an increase in intra-abdominal fat followed by a loss of lean body mass after menopause (Morita et al. Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not. Additionally, the incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women. Hormone Replacement Therapy: Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement has changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy. If so, they can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse. Menopause and Ethnicity: In a review of studies that mentioned menopause, symptoms varied greatly across countries, geographic regions, and even across ethnic groups within the same region (Palacios, Henderson, & Siseles, 2010). After controlling for age, educational level, general health status, and economic stressors, white women were more likely to disclose symptoms of depression, irritability, forgetfulness, and headaches compared to women in the other racial/ethnic groups. African American women experienced more night sweats, but this varied across research sites. Finally, Chinese American and Japanese American reported fewer menopausal symptoms when compared to the women in the other groups. Overall, the Chinese and Japanese group reported the fewest symptoms, while 325 white women reported more mental health symptoms and African American women reported more physical symptoms. Further, the prevalence of language specific to menopause is an important indicator of the occurrence of menopausal symptoms in a culture. Hmong tribal women living in Australia and Mayan women report that there is no word for "hot flashes" and both groups did not experience these symptoms (Yick-Flanagan, 2013). When asked about physical changes during menopause, the Hmong women reported lighter or no periods. They also reported no emotional symptoms and found the concept of emotional difficulties caused by menopause amusing (Thurston & Vissandjee, 2005). Similarly, a study with First Nation Source women in Canada found there was no single word for "menopause" in the Oji-Cree or Ojibway languages, with women referring to menopause only as "that time when periods stop" (Madden, St Pierre-Hansen & Kelly, 2010). While some women focus on menopause as a loss of youth, womanhood, and physical attractiveness, career-oriented women tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Japanese women perceive menopause as a transition from motherhood to a more whole person, and they no longer feel obligated to fulfill certain expected social roles, such as the duty to be a mother (Kagawa-Singer, Wu, & Kawanishi, 2002). Overall, menopause signifies many different things to women around the world and there is no typical experience. Erectile dysfunction refers to the inability to achieve an erection or an inconsistent ability to achieve an erection (Swierzewski, 2015). Plaque is made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other substances found in the blood. If testosterone levels decline significantly, it is referred to as andropause or late-onset hypogonadism. Identifying whether testosterone levels are low is difficult because individual blood levels vary greatly. Low testosterone is also associated with medical conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, and testicular cancer. Most men with low testosterone do not have related problems (Berkeley Wellness, 2011). For women, decreased sexual desire and pain during vaginal intercourse because of menopausal changes have been identified (Schick et al. A woman may also notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal which can affect overall pleasure (Carroll, 2016). Men may require more direct stimulation for an erection and the erection may be delayed or less firm (Carroll, 2016). As previously discussed men may experience erectile dysfunction or experience a medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning. Couples can continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. Risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, and couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. Practicing safe sex is important at any age, but unfortunately adults over the age of 40 have the lowest rates of condom use (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010). Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships. Brain Functioning the brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults, but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences.

For example symptoms 6 days before period purchase norpace once a day, California saw an increase of 273% in reported cases from 1987 through 1998 (Byrd treatment kennel cough buy norpace 150 mg without a prescription, 2002) symptoms copd purchase 150mg norpace with mastercard. Although it is difficult to interpret this increase symptoms indigestion cheap norpace online amex, it is possible that the rise in prevalence is the result of the broadening of the diagnosis medicine vs medication generic norpace 100 mg amex, increased efforts to identify cases in the community medicine 6 year cheap norpace uk, and greater awareness and acceptance of the diagnosis. In addition, mental health professionals are now more knowledgeable about autism spectrum disorder and are better equipped to make the diagnosis, even in subtle cases (Novella, 2008). The exact causes of autism spectrum disorder remain unknown despite massive research efforts over the last two decades (Meek, Lemery-Chalfant, Jahromi, & Valiente, 2013). Many different genes and gene mutations have been implicated in autism (Meek et al. Among the genes involved are those important in the formation of synaptic circuits that facilitate communication between different areas of the brain (Gauthier et al. A number of environmental factors are also thought to be associated with increased risk for autism spectrum disorder, at least in part, because they contribute to new mutations. These factors include exposure to pollutants, such as plant emissions and mercury, urban versus rural residence, and vitamin D deficiency (Kinney, Barch, Chayka, Napoleon, & Munir, 2009). A recent Swedish study looking at the records of over one million children born between 1973 and 2014 found that exposure to prenatal infections increased the risk for autism spectrum disorders (al-Haddad et al. Children born to mothers with an infection during pregnancy has a 79% increased risk of autism. Infections included: sepsis, flu, pneumonia, meningitis, encephalitis, an infection of the placental tissues or kidneys, or a urinary tract infection. One possible reason for the autism diagnosis is that the fetal brain is extremely vulnerable to damage from infections and inflammation. These results highlighted the importance of pregnant women receiving a flu vaccination and avoiding any infections during pregnancy. There is no scientific evidence that a link exists between autism and vaccinations (Hughes, 2007). Indeed, a recent study compared the vaccination histories of 256 children with autism spectrum disorder with that of 752 control children across three time periods during their first two years of life (birth to 3 months, birth to 7 months, and birth to 2 years) (DeStefano, Price, & Weintraub, 2013). At the time of the study, the children were between 6 and 13 years old, and their prior vaccination records were obtained. Because vaccines contain immunogens 138 (substances that fight infections), the investigators examined medical records to see how many immunogens children received to determine if those children who received more immunogens were at greater risk for developing autism spectrum disorder. The results of this study clearly demonstrated that the quantity of immunogens from vaccines received during the first two years of life were not at all related to the development of autism spectrum disorder. Guilt the trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiative action (Erikson, 1982). Children may want to build a fort with the cushions from the living room couch or open a lemonade stand in the driveway or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Self-Concept and Self-Esteem Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. Self-concept is our self-description according to various categories, such as our external and internal qualities. The emergence of cognitive skills in this age group results in improved perceptions of the self. If asked to describe yourself to others you would likely provide some physical descriptors, group affiliation, personality traits, behavioral quirks, values, and beliefs. When researchers ask young children the same open-ended question, the children provide physical descriptors, preferred activities, and favorite possessions. Thus, a three-year-old might describe herself as a three years-old girl with red hair, who likes to play with legos. Harter and Pike (1984) challenged the method of measuring personality with an open-ended question as they felt that language limitations were hindering the ability of young children to express their self-knowledge. They suggested a change to the method of measuring self-concept in young children, whereby researchers provide statements that ask whether something is true of the child. However, this does not mean that preschool children are exempt from negative self-evaluations. Preschool children with insecure attachments to their caregivers tend to have lower self-esteem at age four (Goodvin et al. Maternal negative affect was also found Source by Goodwin and her colleagues to produce more negative self-evaluations in preschool children. It includes response initiation, the ability to not initiate a behavior before you have evaluated all the information, response inhibition, the ability to stop a behavior that has already begun, and delayed gratification, the ability to hold out for a larger reward by forgoing a smaller immediate reward (Dougherty, Marsh, Mathias, & Swann, 2005). It is in early childhood that we see the start of self-control, a process that takes many years to fully develop. Walter Mischel and his colleagues over the years have found that the ability to delay gratification at the age of four predicted better academic performance and health later in life (Mischel, et al. As executive function improves, children become less impulsive (Traverso, Viterbori, & Usai, 2015). Gender Another important dimension of the self is the sense of self as male or female. Preschool aged children become increasingly interested in finding out the differences between boys and girls, both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While two-year-olds can 140 identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. Gender is the cultural, social and psychological meanings associated with masculinity and feminity (Spears Brown & Jewell, 2018). The development of gender identity appears to be due to an interaction among biological, social and representational influences (Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Children learn about what is acceptable for females and males early, and in fact, this socialization may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Consider parents of newborns, shown a 7-pound, 20-inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Female infants are held more, talked to more frequently and given direct eye contact, while male infant interactions are often mediated through a toy or activity. Source As they age, sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion, while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home, such as cleaning or cooking that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems and daughters are more likely to be given assistance, even when they are working on an answer. For example, parents talk to sons more in detail about science, and they discuss numbers and counting twice as often than with daughters (Chang, Sandhofer, & Brown, 2011). How are these beliefs about behaviors and expectations based on gender transmitted to children Theories of Gender Development One theory of gender development in children is social learning theory, which argues that behavior is learned through observation, modeling, reinforcement, and punishment (Bandura, 1997). Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles that have been presented to them since birth and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory states that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are 141 appropriate for each gender. Cognitive social learning theory also emphasizes reinforcement, punishment, and imitation, but adds cognitive processes. Once children learn the significance of gender, they regulate their own behavior based on internalized gender norms (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Another theory is that children develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness, which is referred to as gender schema theory (Bem, 1981). Once children have identified with a particular gender, they seek out information about gender traits, behaviors, and roles. This theory is more constructivist as children are actively acquiring their gender. For example, friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls, and popularity may be based on what is considered ideal behavior for their gender. Developmental intergroup theory states that many of our gender stereotypes are so strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). Transgender Children Many young children do not conform to the gender roles modeled by the culture and even push back against assigned roles. However, a small percentage of children actively reject the toys, clothing, and anatomy of their assigned sex and state they prefer the toys, clothing and anatomy of the opposite sex. Transgender adults have stated that they identified with the opposite gender as soon as they began talking (Russo, 2016). Current research is now looking at those young children who identify as transgender and have socially transitioned. In 2013, a longitudinal study following 300 socially transitioned transgender children between the ages of 3 and 12 began (Olson & Gulgoz, 2018). Socially transitioned transgender children identify with the gender opposite than the one assigned at birth, and they change their appearance and pronouns to reflect their gender identity. Findings from the study indicated that the gender development of these socially transitioned children looked similar to the gender development of cisgender children, or those whose gender and sex assignment at birth matched. These socially transitioned transgender children exhibited similar gender preferences and gender identities as their gender matched peers. Further, these children who were living everyday according to their gender identity and were supported by their families, exhibited positive mental health. Some individuals who identify as transgender are intersex; that is born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes (Jarne & Auld, 2006). There are dozens of intersex conditions, and intersex individuals demonstrate the diverse variations of biological sex. How much does gender matter for children: Starting at birth, children learn the social meanings of gender from adults and their culture. Therefore, when children make choices regarding their gender identification, expression, and behavior that may be contrary to gender stereotypes, it is important that they feel supported by the caring adults in their lives. This support allows children to feel valued, resilient, and develop a secure sense of self (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2015). Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships. This kind of parenting style has been described as authoritative (Baumrind, Source 2013). Parents allow negotiation where appropriate, and consequently this type of parenting is considered more democratic. Authoritarian is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggests that authoritarian parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer targets perhaps as bullies toward peers. Permissive parenting involves holding expectations of children that are below what could be reasonably expected from them. Parents are warm and communicative but provide little structure for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits. These children can suffer in school and in their relationships with their peers (Gecas & Self, 1991). Sometimes parenting styles change from one child to the next or in times when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting.

Discount norpace 100 mg otc. My First Multiple Sclerosis Symptoms.