Ivan Ho Wong, MD, PhD

- Associate Professor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery,

- Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School

- of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

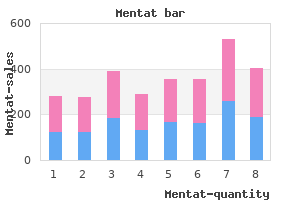

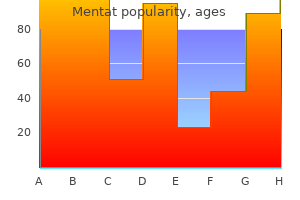

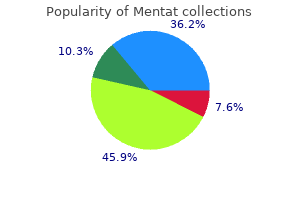

Twenty-four hour physician availability is neces unstable patients treatment 02 bournemouth buy mentat 60caps fast delivery, one should consider obtaining serum levels sary to handle any acute situations that may arise during hos in order to ensure achievement of therapeutic drug concentra pitalization treatment xyy 60caps mentat otc. It is also ideal to ensure that patients response team should be available in the event of the need for being dismissed from epilepsy monitoring have appropriate acute airway management and resuscitation medicine for the people buy mentat 60 caps with visa. Side rails with pads are reason Clinical Localization: Ictal Semiology able to help prevent patients from falling out of bed during a seizure; however they can pose an unintended risk in some Analysis of ictal semiology can provide valuable localizing cases symptoms neuropathy purchase mentat no prescription, particularly those with hypermotor semiologies medicine journals impact factor buy mentat 60 caps line. Tongue bite wounds are not the possibility of multiple seizure foci treatment ulcer mentat 60 caps on line, which may influence infrequent but rarely require treatment beyond conservative the prospects for surgical success. In terms of lobar localization, temporal versus frontal lobar localization could be correctly determined in 76% of patients by semiologic analysis of a cohort of patients with Ictal Speech Preservation and Aphasia. Lateralizing and localizing signs tion in temporal lobe seizures is highly suggestive of nondom of significance in epilepsy surgery patients are summarized in inant lateralization (28). In one prospective study, nearly all patients with influenced by the propagation of the discharge from one corti nondominant temporal lobe seizures were able to read a test cal region to another, which can lead to false localization phrase within 1 minute of seizure onset, while no patient with (26,27). For example, aphasia may occur in patients with dominant temporal lobe seizures were able to read until seizures of nondominant temporal origin if spread to the greater than 1 minute had passed (30). Ictal aphasia is less speech-dominant hemisphere occurs by the time language is common in dominant hemisphere extratemporal seizures (31), tested during the seizure. Second, while the specificity of some except for those seizures arising in close proximity to the oper of the semiologic signs approach 90%, the sensitivity is not as culum. Indeed, localizing clinical signs may be completely important to make sure that any detected speech alteration is absent in some patients (23,25). Third, seizures arising in not primarily due to orolingual motor effects as opposed to functionally silent regions may not show clinical manifesta language, as the localizing implications are different. Finally, some regions of the brain lead primarily to sub hand posturing is associated with contralateral seizure onset jective perceptual changes that are not appreciable on review (32). This sign is common in temporal lobe seizures, and of video data due to the absence of a motor or behavioral cor thought to be due to seizure propagation to neighboring basal relate. Unilateral manual Lateralizing Signs automatisms are of lateralizing significance primarily when Some clinical signs are primarily of lateralizing value. These seen in association with unilateral dystonic posturing affecting are summarized in Table 74. Distinguishing unilateral automatisms from clonus is a secondary generalized seizure typically occurs in the direc important as the lateralizing implications are opposite. A: Unilateral dystonic hand posturing on the left and unforced head-turn to the right during a right temporal seizure in a patient with right mesial temporal sclerosis. B: Forced head-turning to the left during progression to a secondary general ized seizure in a seizure of right temporal origin secondary to mesial temporal sclerosis. C: Left facial contracture and clonus during a seizure of right frontocentral onset in a patient with a right peri Rolandic cortical dysplasia. D: Unilateral postictal nose wiping involving the ipsilateral hand in a patient with right temporal seizures. F: Fencing posture in a patient with a secondary generalized seizure of right temporal neocortical onset. H: Ictal paresis involving the left upper extremity during a right parietal seizure of unknown etiology. A postictal confusional period lasting a few to sev case it is of less lateralizing significance (36). Nose wiping with one hand following seizures and those with limited bitemporal involvement may temporal lobe seizures typically involves the ipsilateral hand not be associated with a significant postictal period (25,41). Postictal nose wiping is more characteristic of temporal lobe than extratemporal seizures. The clinical presentations of extratem illustrated in a patient following a right temporal lobe seizure poral frontal lobe seizures are protean. In contrast to temporal lobe seizures, frontal lobe seizure auras, if present, Ictal Spitting. Ictal spitting is usually associated with non are usually nondescript, consisting of vague light-headedness dominant temporal lobe seizures, however dominant lateral or fear. Frontal seizures are often brief, lasting 1 minute or ization has also been reported (38). It is thought to be due to less, and are sometimes characterized by an explosive onset, hypersalivation secondary to stimulation of the central auto with prominent hypermotor activity and complex lower nomic network. While nocturnal predominance may be seen in temporal lobe seizures as well, a seizure pattern of multiple brief clusters of Unilateral Piloerection. This typically occurs ipsilateral to the seizures occurring exclusively during sleep is more characteris seizure focus and is usually seen in temporal lobe seizures (39). Nongeneralized seizures of frontal origin are often followed by a relatively brief postictal period M2E, Fencing, Figure of 4 Posturing. However, not all frontal to a posture consisting of contralateral shoulder abduction, lobe seizures behave in the same manner. Ictal paresis can be mis and left parasagittal and right and left temporal head electrodes taken for transient ischemic attacks. An example is shown in should be utilized placed at standard interelectrode distances. Additional inferior temporal electrodes should be considered in patients where a temporal lobe focus is suspected. Lobar Localization Nasopharyngeal, foramen ovale and transsphenoidal electrodes Semiology can help with lobar localization as well, particularly have been advocated by some to improve the sensitivity and in differentiating temporal and extratemporal seizures (25,41). Temporal localization is suggested by electrodes has not been confirmed by all investigators, however, the presence of an aura of experiential phenomena such as an and are not routinely used (45,46). Also, the presence of interictal epileptiform abnormalities may be of prognostic value in certain epilepsy abnormalities beyond the boundaries of the epileptogenic syndromes. In one study of temporal lobectomy patients, zone or contralateral to the suspected focus may influence sur fewer (29%) patients with frequent spikes (60 spikes per gical prognosis and the chances for eventual antiepileptic drug hour) experienced an excellent surgical outcome from a stan discontinuance. Generalized interictal activity may be seen in dard temporal lobectomy with amygdalohippocampectomy some cases which may suggest the presence of more than one compared to 81% with infrequent spikes (60 spikes per epilepsy mechanism in a given patient. Concordance with other localizing data of recorded seizures and 72% of patients, and false localiza portends a more favorable prognosis than patients with dis tion occurred in 6% (53). A: Right temporal sharp waves and temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity in a patient with right tem poral lobe epilepsy secondary to mesial temporal sclerosis. B: Left occipital-posterior temporal spikes in a patient with a left medial occipital cortical dysplasia. D: Repetitive left frontal spikes in a patient with nonlesional frontal lobe epilepsy localized to the left dorsolateral frontal region. However, such high-frequency discharges are making final decisions about surgical treatment (54,55). In frontal lobe seizures, arti ited by the fact that the portion of the cortical surface amenable fact secondary to hypermotor ictal behavior may obscure the to scalp electrode acquisition is constrained by the discrepancy recording. Finally, it is recognized that two thirds of the cortical features of the seizure discharge. High-frequency discharges greater than 100 Hz are gential to the electrode recording surface. The presence of cortical or cerebral pathology quency and patterns seen (58,64,68,69). In such cases, intracranial monitoring may Occipital seizures are also known to propagate early to the ultimately be required to resolve localization. Mesial temporal temporal lobes, giving rise to the potential for false localiza and lateral frontal seizure foci are the regions most amenable tion (25,27,57,58). The seizure pattern in temporal lobe epilepsy where localized slowing can some recorded in an individual patient with a single epileptogenic times be seen in the ipsilateral temporal region (80). Mesial temporal seizures typically are manifest as an should raise the possibility of a relatively large epileptogenic evolving rhythmic theta discharge arising over the ipsilateral zone or multiple seizure foci. A typical right mesial same brain region in different patients may show interindivid temporal seizure is shown in Figure 74. C: the right temporal discharge fre quency decreases toward the end of the seizure to the delta frequency range. D: Subtle lateralized postic tal delta slowing and attenuation of the background is present over the right hemispheric derivations following seizure termination. At seizure termination, the discharge frequency fuse and is more apparent in seizures arising out of sleep (82). This is typically seen in diffuse, evolving into a more lateralized discharge over the seizures which spread from one hippocampus to the other ipsilateral temporal region after the first several seconds of the prior to propagation to the ipsilateral temporal neocortex. Mesial temporal depth electrode recordings may of a vertical dipole in the mesial temporal region with the be necessary to resolve seizure lateralization in such cases. In one study, the mean discharge fre with mesial frontal seizures including generalized spike and quency at seizure onset in neocortical temporal seizures was wave, a diffuse electrodecremental pattern, and rhythmic ver 1 Hz less than mesial temporal seizures (65). In the absence of a lar 5 to 9-Hz inferotemporal rhythm, and occasionally by a structural or functional imaging abnormality in such cases, vertex/parasagittal positive rhythm of the same frequency. In another series, mesial tempo seizures may manifest as a focal low-amplitude high-frequency ral seizures were more likely to show fast rhythmic sharp discharge, an example of which is depicted in Figure 74. This can cause erroneous localiza eate mesial and neocortical temporal seizures (44,62). Orbital However, intracranial monitoring is usually necessary when frontal seizures can also spread to other regions of the frontal definitive electrophysiologic clarification is required (46). A localizing ictal discharge may not be present in propagation to the temporal region (88). In one large surgical series, a local ture that can reliably distinguish a propagated temporal dis izing discharge at onset was seen over the temporo-occipital charge from a temporal origin rhythm (89). The parietal lobe is the least common area ing propagated versus temporal onset rhythms, but have not of seizure onset in partial epilepsy. Recognition of the various expressions of anxiety, psychosis, and aggression in epilepsy. Diagnosis and management of depression and psychosis in children and adolescents with epilepsy. Epileptic Seizures: Pathophysiology and Clinical surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy [see comment]. Intracranial electroencephalog electroencephalography and seizure semiology improves patient lateral raphy seizure onset patterns and surgical outcomes in nonlesional ization in temporal lobe epilepsy. Recommendations regarding the require ogy in distinguishing frontal lobe seizures and temporal lobe seizures. Improvement in the perfor mesial temporal origin: electroclinical and metabolic patterns. State-dependent spike detection: concepts and functional connections of the living human brain. Ictal speech, postictal language dysfunction, and Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. Clinical and electrographic mani partial seizures of temporal lobe onset: a new lateralizing sign [see com festations of lesional neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy. Ictus emeticus: an electroclini and electroencephalographic study of 46 pathologically proven cases. Occipital lobe epilepsy: rior temporal lobectomy for intractable epilepsy: a multivariate study. Noninvasive electroencephalography and mesial tem effectiveness for intractable nonlesional focal epilepsy. Electroencephalographic studies of thalamic hamartomas: evaluation of patients undergoing chronic intracra simple partial seizures with subdural electrode recordings. The value of closely spaced synchrony on recording scalp electroencephalography ictal patterns. J Neurol lobe origin: clinical characteristics, localizing signs, and results of surgery. Surgical management of malacias for intractable epilepsy: outcome and prognostic factors [see parietal lobe epilepsy. Although and to investigate the pathophysiology of partial and general there are some individual differences in tracer distribution (1), ized seizure disorders. The few reports of false lateralization life of [15O]water renders it suitable for capturing the brief have occurred after surgery (3) was performed, when interpre activity of cognitive processes. This may reflect the distant projection of func result in misleading information and erroneous conclusions tional loss in mesial structures. Voxel-based statistical methods performed in a stan contralateral hypometabolism appear to be reversible with dard anatomic atlas that allows comparison of individual successful temporal lobectomy (24). Conflicting, localizing, or lateralization data nearly there is sufficient variability among patients that individual always merit invasive monitoring.

These eye move is known about the presence of baseline stra ments represent seizure activity medications similar to adderall discount mentat 60caps fast delivery, and often bismus treatment writing order mentat 60caps with amex. For example treatment anal fissure buy mentat in india, injury of gaze for several hours medicine grace potter order discount mentat online, causing lateral gaze to the oculomotor nucleus or nerve produces deviation toward the side of the affected cor exodeviation of the involved eye symptoms colon cancer generic mentat 60caps on line. Dam Combined loss of adduction and vertical age to the lateral pons symptoms kidney failure dogs buy mentat with mastercard, on the other hand, may movements in one eye indicates an oculomotor cause loss of eye movements toward that side nerve impairment. The lateral gaze devi severe ptosis on that side (so that if the patient ation in such patients cannot be overcome by is awake, he or she may not be aware of dip vestibular stimulation, whereas vigorous ocu lopia). In rare cases with a lesion of the ocu locephalic or caloric stimulation usually over lomotor nucleus, the weakness of the superior comes lateral gaze deviation due to a cortical rectus will be on the side opposite the other gaze paresis. The classical nerve paresis due to brainstem injury or com cause of oculogyric crises was postencephalitic pression of the oculomotor nerve by uncal her parkinsonism. If awake, the patient typically attempts to compensate by tilting the head toward that shoulder. Absence of abduction of a single eye suggests injury to the abducens nerve ei Skew deviation refers to vertical dysconjugate ther within the brainstem or along its course to gaze, with one eye displaced downward com the orbit. Skew deviation is due so the presence of an isolated abducens palsy either to a lesion in the lateral rostral medulla may be misleading. Bilateral lesions of the medial longitudinal fasciculus impair ad these are slow, random deviations of eye po duction of both eyes as well as vertical oculo sition that are similar to the eye movements cephalic and vestibulo-ocular eye movements, seen in normal individuals during light sleep. Most roving descending inputs that relax the opposing eye eye movements are predominantly horizontal, muscles when a movement is made, so that all although some vertical movements may also six muscles contract when attempts are made occur. A variety of re have been reported in patients with a variety of lated eye movements have been described in structural injuries to the brainstem or even cluding inverse bobbing (rapid elevation of bilateral cerebral infarcts that leave the ocu the eyes, with bobbing downward back to pri lomotor system largely intact, but are most mary position) and both dipping (downward common during metabolic encephalopathies. The implications of Nystagmus refers to repetitive rapid (saccadic) these unusual eye movements are similar to eye movements, often alternating with a slow those of ocular bobbing: a lower brainstem in drift in the opposite direction. This is followed by tinuous seizure activity with versive eye move reversal of the movements. Seesaw nystagmus appears to be due Retractory nystagmus consists of irregular in most cases to lesions near the rostral end jerks of both globes back into the orbit, of the periaqueductal gray matter, perhaps sometimes occurring spontaneously but other involving the rostral interstitial nucleus of 133 times on attempted upgaze. It may occasionally be seen also in during retractory nystagmus shows that the comatose patients, sometimes accompanied by retractions consist of simultaneous contrac ocular bobbing, and in such a setting may in 127 134 tions of all six extraocular muscles. As patients become more the motor examination in a stuporous or co deeply stuporous, muscle tone tends to de matose patient is, of necessity, quite different crease and these pathologic forms of rigidity are from the patient who is awake and cooperative. Rooting, the movement is slowed to a near stop by the glabellar, snout, palmomental, and other re resistance, at which point the resistance col exes are often seen in such patients. On the patient is asleep or there is impairment of con other hand, the grasp reex is generally seen sciousness. In contrast, during diffuse meta only in patients who have some degree of bi 137 bolic encephalopathies, many otherwise nor lateral prefrontal impairment. It is elicited mal patients develop paratonic rigidity, also by gently stroking the palm of the patient with called gegenhalten. The pull reex is a variant in which the movement increases, as if the patient were the examiner curls his or her ngers under the willfully resisting the examiner. Grasping disappears when the lesion tient does not respond to voice or gentle shak involves the motor cortex and causes hemi ing, arousability and motor responses are tes paresis. Motor responses to noxious stimulation in patients with acute cerebral dysfunction. As the lesion progresses into the midbrain, there is generally a shift to decerebrate posturing (C), in which there is extensor posturing of both upper and lower extremities. An appropriate re mals, these patterns of motor response may be sponse is one that attempts to escape the stim produced by brain lesions of several different ulus, such as pushing the stimulus away or kinds and locations and the patterns of motor attempting to avoid the stimulus. There is a tendency and motor connections within the spinal cord for lesions that cause decorticate rigidity to be and brainstem, from a stereotyped withdrawal more rostral and less severe than those caus response, such as a triple exion withdrawal of ing decerebrate rigidity. The stereotyped withdrawal they simply describe the movements that are response is not responsive to the nature of the seen rather than attempt to t them to com stimulus. The fully developed occur in patients with severe brain injuries or response consists of a relatively slow (as op even brain death. It is also important to assess posed to quick withdrawal) exion of the arm, asymmetries of response. Failure to withdraw wrist, and ngers with adduction in the upper on one side may indicate either a sensory or a extremity and extension, internal rotation, and motor impairment, but if there is evidence of vigorous plantar exion of the lower extremity. Such withdraw on both sides, accompanied by facial fragmentary patterns have the same localizing grimacing, may indicate bilateral motor im signicance as the fully developed postural pairment below the level of the pons. The decorticate pattern is generally pro Most appear only in response to noxious stim duced by extensive lesions involving dysfunc uli or are greatly exaggerated by such stimuli. Such patients typically have represents the response to endogenous stim normal ocular motility. A similar pattern of uli, ranging from meningeal irritation to an oc motor response may be seen in patients with cult bodily injury to an overdistended bladder. The arms are held in adduction and ex from experimental physiology to certain pat tension with the wrists fully pronated. Tonic First, these terms imply more than we really neck reexes (rotation of the head causes hy know about the site of the underlying neuro perextension of the arm on the side toward Examination of the Comatose Patient 75 which the nose is turned and exion of the repeatedly conrmed. The physiologic basis of other arm; extension of the head may cause ex this motor pattern is not understood, but it may tension of the arms and relaxation of the legs, represent the transition from the extensor pos while exion of the head leads to the opposite turing seen with lower midbrain and high pon response) can usually be elicited. As with de tine injuries to the spinal shock (accidity) or corticate posturing, fragments of decerebrate even exor responses seen from stimulating posturing are sometimes seen. De the main purpose of the foregoing review of cerebrate posturing in experimental animals the examination of a comatose patient is to dis usually results from a transecting lesion at the tinguish patients with structural lesions of the level between the superior and inferior colli brain from those with metabolic lesions. It is believed to be due to the release of vestibulospinal postural reexes from fore imaging. The level of brainstem dys require an extensive laboratory evaluation to de function that produces this response in humans ne the cause. Therefore, the physician should be more severe nding than decorticate postur come familiar with the few focal neurologic ing; for example, in the Jennett and Teasdale ndings that are seen in patients with diffuse series, only 10% of comatose patients with head metabolic causes of coma, and understand their injury who demonstrated decerebrate postur implications for the diagnosis of the metabolic 139 problem. Most patients with decere brate rigidity have either massive and bilateral forebrain lesions causing rostrocaudal deteri oration of the brainstem as diencephalic dys Respiratory Responses function evolves into midbrain dysfunction (see Chapter 3), or a posterior fossa lesion that the range of normal respiratory responses compresses or damages the midbrain and ros includes the Cheyne-Stokes pattern of breath tral pons. Their color may become seen in patients with injury to the lower dusky during the oxygen desaturation that ac brainstem, at roughly the level of the vestibular companies each period of apnea. This must be cause the seizure usually results in the release distinguished from sepsis, hepatic encephalop of adrenalin, the pupils typically are large after athy, or cardiac dysfunction, conditions that of a seizure. The may suppress all brainstem responses, includ nature of the primary insult is determined by ing pupillary light reactions, and simulate brain whether the blood pH is low (metabolic aci death (see Chapter 6). As a result, it is generally therefore are a useful differential point in iden necessary to do an imaging study (see below) tifying psychogenic unresponsiveness. Acute administration of phenytoin quite often However, similar pinpoint but reactive pupils has this effect, which may persist for 6 to 12 146 may be seen in opiate intoxication. Occasionally, patients who have in patients who present with pinpoint pupils and gested an overdose of various tricyclic antide coma, it is necessary to administer an opiate pressants may also have absence of vestibulo 147 antagonist such as naloxone to reverse poten ocular responses. In or so, it is necessary to re-examine the patient such cases, the relationship of the loss of eye 15 to 30 minutes later to make sure that the movements to the impairment of conscious Examination of the Comatose Patient 77 ness may be confusing, and the prognosis may sibility of false localizing signs in patients with be much better than would be indicated by the metabolic causes of coma, unless a structural lack of these brainstem reexes, particularly lesion can be ruled out, it is still usually nec if the patient receives early plasmapheresis or essary to proceed as if the coma has a structural intravenous immune globulin. It can be done at the bedside creased intracranial pressure, even due to non within a matter of a few minutes, and it pro 150 focal causes such as pseudotumor cerebri. The same may be true for some types of metabolic coma, such as meningitis or hypoglycemia. Some have suggested Because of the propensity for some metabolic that the focal signs represent the unmasking of comas to cause focal neurologic signs, it is subclinical neurologic impairment. It is true important to perform basic blood and urine that most metabolic causes of coma may ex testing on virtually every patient who presents acerbate a pre-existing neurologic focal nd with coma. Blood gases should be drawn hypoglycemia are more common in children if there is any suspicion of respiratory insuf than adults, again suggesting the absence of an ciency or acid-base abnormality. Similarly, focal then be collected for urinalysis and screening decits are observed with hypertensive en for toxic substances or drugs (which may no cephalopathy, but in this case imaging usually longer be detectable in the bloodstream). In a identies brain edema consistent with these woman of reproductive age, pregnancy test focal neurologic decits. Cortical blindness is ing should also be done as this may affect the the most common of these decits; edema evaluation. A bedside mea netic resonance images, the so-called posterior surement of blood glucose is sufficiently ac 154 leukoencephalopathy syndrome. However, if glu hepatic coma, may also cause either decere cose is given, 100 mg of thiamine should be brate or decorticate posturing. Hence, they are less of ever, subacute infarction may become isodense ten used for primary scanning of patients with with brain during the second week, and hem coma. Panel (B) shows the perfusion blood ow map, indicating that there is very low ow within the left middle cerebral artery distribution, but that there is also impairment of blood ow in both anterior cerebral arteries, consistent with loss of the contribution from the left internal carotid artery. Its presence serves as a marker of as ow of blood in arteries, particularly the mid trocytes. Levels are decreased in ative drugs that may alter some of the clini 158,159 hyponatremia, chronic hepatic encephalopathy, cal ndings (see Chapter 8). The injection of gas ergy metabolism in both neurons and astro lled microbubbles enhances the sonographic cytes. The total creatine peak remains constant, echo and provides better delineation of blood allowing other peaks to be calculated as ratios ow, occlusions, pseudo-occlusions, stenosis, 162 to the height of the creatine peak. Hence, deferring lumbar puncture in history of presumed gastroenteritis, with fever, such cases until after the scanning procedure nausea, and vomiting. Examination of blinking, and may present as merely confused, the red blood cells under the microscope im drowsy, or even stuporous or comatose. In that they have been in the extravascular space one series, 8% of comatose patients were found for some time. Un objective electrophysiologic assay of cortical fortunately, some patients with a clinical and function in patients who do not respond to electroencephalographic diagnosis of noncon normal sensory stimuli. Although they do tients is usually more regular and less variable not provide reliable information on the loca than in an awake patient, and it is not inhibited tion of a lesion in the brainstem, both auditory 163 by opening the eyes. Simple bedside assess tion of the upper alimentary tract in the medulla ment of level of consciousness: comparison of two oblongata in the rat: the nucleus ambiguus. Projections of the aortic normalities and location of the intracranial aneurysm nerve to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the rabbit. Post-hyperventi spiratory failure and unilateral caudal brainstem in lation apnoea in patients with brain damage. Glutaminergic breathing in patients with acute supra and infra vagal afferents may mediate both retching and gastric Examination of the Comatose Patient 85 adaptive relaxation in dogs. Ocular motor disorders associ relative afferent pupillary defect secondary to con ated with cerebellar lesions: pathophysiology and top tralateral midbrain compression. Localizing value of torsional nystagmus in small mid Pharmacological testing of anisocoria. Using video pillomotor and accommodation bers in the oculo oculography for galvanic evoked vestibulo-ocular motor nerve: experimental observations on paralytic monitoring in comatose patients. Report of a patient in coma after hyperextension Detection of subarachnoid haemorrhage with mag head injury. Volume nonconvulsive status epilepticus: nonconvulsive sta measurement of cerebral blood ow: assessment of tus epilepticus is underdiagnosed, potentially over cerebral circulatory arrest. These processes include a wide range may cause these changes include tumor, hem of space-occupying lesions such as tumor, he orrhage, infarct, trauma, or infection. The time, however, is short and should physician must rst decide whether the patient be counted in minutes rather than hours or is indeed stuporous or comatose, distinguish days. More difficult is distinguishing structural from met abolic causes of stupor or coma. However, neu ness, suprasellar tumors typically cause visual rons are dependent upon axonal transport to eld decits, classically a bitemporal hemia supply critical proteins and mitochondria to nopsia, although a wide range of optic nerve or their terminals, and to transport used or dam tract injuries may also occur. When a compressive lactorrhea and amenorrhea, as prolactin is the lesion results in displacement of the structures sole anterior pituitary hormone under negative of the arousal system, consciousness may be regulation, and it is typically elevated when come impaired, as described in the sections the pituitary stalk is damaged. Pineal masses compress the pre When a cerebral hemisphere is compressed by tectal area as well. In such patients, the hemorrhages, infarctions, or abscesses, although Structural Causes of Stupor and Coma 91 occasionally extra-axial lesions, such as a sub size and often causes signs of local injury be dural or epidural hematoma, may have a sim fore consciousness is impaired.

Declines in seahorse occurrence and abundance are being recorded in areas such as the Philippines symptoms ms order on line mentat, where subsistence communities rely upon collection of seahorses to supplement their income symptoms vitamin b deficiency generic mentat 60caps online. Overfishing in recent years is leading to the collapse of these fisheries with negative implications for species persistence in some areas with highly overexploited populations medicine bottle purchase cheap mentat online. The international zoo and aquarium community is establishing captive-breeding programs for seahorses (with formal registries of populations) to allow distribution of popular exhibit species to interested institutions medications in carry on luggage cheap mentat amex. While this approach will improve the potential for interpretation and the condition of the captive populations in public facilities medications 5 songs buy cheap mentat 60 caps line, it is recognised that wild collection for the aquarium trade will continue to be required symptoms quivering lips purchase mentat on line. Public aquariums have the potential to play an important role in the conservation of wild seahorse populations. For those institutions that wish to display seahorses, captive-bred animals should be considered before wild-caught animals. It is recommended that any aquariums that receive Customs-seized seahorses maintain records on initial conditions, survival and reproduction. In the hope that the Guidelines can be improved, the Secretariat would welcome comments, which should be addressed to the Scientific Support Unit. The guidelines for the transport of fish in plastic bags is appended to this chapter. Transportation of Seahorses During transportation seahorses are enclosed in a restrictive container that does not allow for ideal water quality parameters and is subject to unpredictable movement orientation and noise levels. Water quality parameters at destination (transit time can be substantially longer due to acclimation time at destination) 9. Whether individuals are captive-bred, caught directly from wild, or have recently been transferred through various exporter/importers Bags should be designed to allow for minimum slop (tall cylinder shapes work well). It is better to have fewer individuals per bag with the use of more bags rather than large bags with a lot of individuals. The most usual method for transporting seadragons is to pack the bags with all water and no air/oxygen above them. This is done to prevent the seadragons from "piping" and getting air/oxygen gas entrained within them. If done correctly, there is enough oxygen dissolved in the water to sustain the animals for quite some time. Other aquariums, howver, report the successful shipping of seadragons packed with oxygen. No oxygen is added to these bags, and the top of the bag is tied off at the surface of the water. Seahorses shipped this way do not get sloshed out of the water in transit and pipefish and seahorses shipped this way do not accidentally ingest air from snapping at the water line in the bag. The bags should be placed into a styrofoam container and that is inside a cardboard box. However, they require the inside of the styrofoam container to be packed with styrofoam peanuts, or shredded newspaper and these bags must not touch each other. For most species, particularly smaller ones, the use of holdfasts in the bag is also recommended. It allows these fish that naturally spend a lot of time holding onto something, a place to rest and conserve energy to reduce their metabolism during shipping. If the box is too large and there are no other bags of fish to be included newspaper or a empty inflated bag(s) should be used to ensure the bags do not move within the box during transport. Handlers could reject the shipment at any stage in the transfer due to water leakage. Documents or inscriptions on bags within the containers providing details of the marine life contents will make unpacking at the final destination much easier. This approach would also be useful if the consignments are transported between countries and subject to custom clearance. Communicate clearly with the final destination of the consignment so that the seahorses will not be delayed. Clearly mark container with the correct labels and make sure that all the shipment documents are complete and with the correct persons. Clearly state to the transit handlers the importance and sensitivity of the consignment. Records need to be kept of success/failure of transport segments, which will allow for clearer communication to all concerned and for modification of the system, if necessary. Education through sharing of information should gradually improve conditions in the trade. Shedd Aquarium) Zoos and aquariums reach a large audience globally, and it is estimated that over 130 million guests visit North American institutions alone each year. A great variety of methods are employed at these institutions to tap into this tremendous educational potential. Some of these include exhibits that take you to another world, classes for people of all ages and interests, and electronic media that reach well beyond the physical location of the exhibits. With the ability to influence so many people, what sort of an effect do we want to have For an ever-increasing number of institutions, the answer lies in the connections amongst animals, their environment, and people. Educators strive not just to inform people about these topics, but also to urge them to action, both locally and on a global scale. We hope to help our guests understand that their actions can change the natural world around them. Exhibits are the first step in reaching our audience about the unique biology of the animals, their habitats, and life history. Interpretive staff holding talks, conducting activities, and hosting animal encounter sessions in front of exhibits help audiences better understand the messages of that exhibit. Zoos and aquaria also serve as venues for education events such as lectures from guest authors and researchers. Teacher training and other methods of reaching classrooms are common and have a multiplication effect allowing more complex messages to reach larger audiences. Through these, and many other means, zoos and aquaria have the opportunity to reach numerous people and help them to make better connections to broader conservation messages. Through education, we can energize the public about what is in need of protection in the marine environment and gather public support for conservation initiatives. Focusing on a single animal, such as the seahorse, excites the interest of a large number of young people and allows us to teach identification with nature, which may influence them to become environmentally concerned adults. Whether we help the public understand how they can protect a single species, a group of animals, or a habitat, our efforts can continue to have an enormous impact on the world we live in. With the continued improvements in husbandry success, more and more aquaria are exhibiting them. Seahorses are ideal species to use as a flagship for conservation as they allow us to highlight some serious and unique conservation concerns. They are not only an example of an animal exploited as a non-food fishery, but also vulnerable to being caught as by-catch. Seahorses also provide an example of how human consumer choices can affect the fates of species. If we look at their use in the traditional medicine, aquarium and curiosity trades, we can then highlight the usage and trade in animals taken from the wild. Basic educational messages may simply focus on species information, habitat, and distribution. Behavioral information may include descriptions of mating behavior and reproduction, as well as information on hunting, predation, and camouflage. More detailed educational messages may encompass statements regarding habitat loss, overfishing, traditional medicine, and other factors threatening wild seahorse populations. As the popularity of seahorses increases, so must the level of the educational messages that we portray. Future Challenges and Opportunities As research continues and more information becomes available about the life history of seahorses, new opportunities arise for education. Lesson plans, informational videos, and literature are tools that are necessary in the classroom. While academic learning is critical, trips to aquaria and zoos energize and excite budding scientists and naturalists. Consequently, the importance of creative graphics and interactive signage increases. Special Syngnathid Exhibits (2005 update) Table 1 gives details of special exhibits for syngnathids held at various aquariums in Europe and North America. Generally, such exhibits have been considered successful and a number of temporary exhibits have now become permanent. Conservation messages and educational materials have been developed and promoted in all these exhibits. Perceived/meas Estimated Conservation Educational Materials Images Other info e-mail Seahorse/ Operation (with any ured success of no. Toledo Zoo Jay Hemdal Seadragons 4/2005 Komodo dragon Remains to be 700,000 Where Panel graphics only Not sure yet jay. These **most popular pages give students activities, questions and things to look for as they travel through each exhibit in the aquarium. These handouts are accompanied by an AquaGuide which is in depth information for teachers. We we did use Project Seahorse archived but Symphony Moody Symphony December Hippocampus kuda still have signs, media through video and we could was a package Gardens 2002 Hippocampus 2002: posters, and a graphics. They possess some novel anatomical and behavioral characteristics with which the veterinary clinician should become familiar in order to render an accurate health evaluation. The majority of the following discussion will focus on seahorses but information on the other groups will be introduced when appropriate. This hard, outer skin can make even simple procedures such as injections a bit of a challenge. They have unique, lobate gill filaments termed lophobranchs that possess fewer lamellae than other teleosts. Grossly, the gills appear as hemispherical structures that have been compared to small chrysanthemums or grape like clusters. In addition, the gills of syngnathids are fairly inaccessible since the operculum has a membranous attachment to the body with only a small opening at the dorsal aspect. The reproductive and anal openings of the female seahorse are both cranial to the small anal fin. The elongated, genital opening of the male located below the anal fin represents the opening to the brood pouch. The brood pouch or brood pouch area is one of the features that is used to distinguish separate families. The alimentary tract of the seahorse consists of an esophagus that leads to a small, pouch-like stomach with no evident pylorus. The liver itself is best visualized at necropsy on the right side of the body extending from the bend in the neck to between 1/3 to of the length of the coelomic cavity. The number of glomeruli in the syngnathid kidney is greatly reduced with some species having almost aglomerular renal tissue. The swim bladder is a simple, single-chambered sac with no anatomical connection to the gut. It begins at the bend in the neck and extends to about 1/3 of the length of the coelomic cavity. In leafy seadragons however, in radiographic contrast studies, it has been noted to possibly consist of a two chambered sac (I. Berzins, the Florida Aquarium, personal communication) but anatomical dissections are incomplete at the moment. Except for their exuberant morning greeting and courtship rituals, they tend to spend most of their day in a rather sedentary mode, grasping some sort of holdfast such as seagrass stems, coral heads, or gorgonians with their muscular, prehensile tails. They gently sway to-and fro with the surge, patiently waiting for small invertebrate prey to come within striking distance. Like the terrestrial chameleon, seahorses are masters of disguise that not only can change their colors to match their surroundings, but can also grow extra skin filaments or cirri in imitation of algal fronds. Some seahorses even host encrusting organisms such as bryozoans, hydroids, or algal filaments to further enhance their camouflage. Physical Examination Visual Assessment When performing an initial physical exam, the posture and buoyancy of the seahorse should be closely scrutinized. They should be evaluated for air entrapment problems such as air in the brood pouch (males) or hyperinflated swim bladders.

If previously unimmunized or if traveling to an area with endemic infection medications januvia cheap 60 caps mentat mastercard, a lactating mother may be given inactivated poliovirus vaccine medicine hat lodge cheap 60caps mentat. Attenuated rubella can be detected in human milk and transmitted to breastfed infants with seroconversion; infections usually are asymptomatic or mild medicine to reduce swelling purchase mentat 60 caps visa. If not administered during pregnancy pretreatment discount mentat 60 caps with mastercard, Tdap should be administered immediately postpartum medicine stone music festival discount mentat amex. Breastfeeding women should receive a seasonal infuenza immunization for the current season when available treatment zollinger ellison syndrome generic mentat 60 caps fast delivery, if not received while pregnant. Either inactivated or live-attenuated infuenza immunizations may be administered during the postpartum period. Transmission of yellow fever vaccine virus via breastfeeding has resulted in meningoencephalitis in the nursing infant. Yellow fever vaccine is contraindicated in the breastfeeding mother in nonemergency situations. Additional recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced-content diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap). The immunogenicity of some recom mended vaccines is enhanced by breastfeeding, but data are lacking as to whether the effcacy of these vaccines is enhanced. Although high concentrations of antipoliovirus antibody in human milk of some mothers theoretically could interfere with the immuno genicity of oral poliovirus vaccine, this is not a concern with inactivated poliovirus vac cine. The effectiveness of rotavirus vaccine in breastfed infants is comparable to that in nonbreastfed infants. Mastitis and breast abscesses have been associated with the presence of bacterial pathogens in human milk. Breast abscesses have the potential to rupture into the ductal system, releasing large numbers of organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus, into milk. Temporary discontinuation of breastfeeding on the affected breast for 24 to 48 hours after surgical drainage and appropriate antimicrobial therapy may be necessary. In general, infectious mastitis resolves with continued lactation during appropriate antimicrobial therapy and does not pose a signifcant risk for the healthy term infant. Even when breastfeeding is interrupted on the affected breast, breastfeeding may continue on the unaffected breast. Women with tuberculosis who have been treated appropriately for 2 or more weeks and who are not considered contagious may breastfeed. Women with tuberculosis disease suspected of being contagious should refrain from breastfeeding and other close contact with the infant because of potential spread through respiratory tract droplet or airborne transmission (see Tuberculosis, p 736). Mycobacterium tuberculosis rarely causes mastitis or a breast abscess, but if a breast abscess caused by M tuberculosis is present, breastfeeding should be discontinued until the mother has received treatment and no longer is consid ered to be contagious. Outbreaks of gram negative bacterial infections in neonatal intensive care units occasionally have been attributed to contaminated human milk specimens that have been collected or stored improperly. Human milk from women other than the biologic mother should be treated according to the guidelines of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America ( Very low birth weight preterm infants, however, are at greater potential risk of symptomatic disease. This effectively will eliminate any theoretical risk of transmission through breastfeeding (see Hepatitis B, p 369). There is no need to delay initiation of breastfeeding until after the infant is immunized. The decision to breastfeed should be based on an informed discussion between a mother and her health care professional. Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that infant prophylaxis with daily nevirapine or nevirapine/zidovudine during breastfeeding signifcantly decreases the risk of postnatal transmission via human milk. Available data indicate that vari-1 ous antiretroviral drugs have differential penetration into human milk; some antiretroviral drugs have concentrations in human milk that are much higher than concentrations in maternal plasma, and other drugs have concentrations in human milk that are much lower than concentrations in plasma or are not detectable. This raises potential concerns regarding infant toxicity as well as the potential for selection of antiretroviral-resistant virus within human milk. In areas where infectious diseases and malnutrition are important causes of infant mortality and where safe, affordable, and sustainable replacement feeding may not be available, infant feeding decisions are more complex. Although apparent maternal-infant transmission has been reported, the rate and timing of transmission have not been established. Women with herpetic lesions on a breast or nipple should refrain from breastfeeding an infant from the affected breast until lesions have resolved but may breastfeed from the unaffected breast when lesions on the affected breast are covered completely to avoid transmission. However, the presence of rubella virus in human milk has not been associated with signif icant disease in infants, and transmission is more likely to occur via other routes. Women with rubella or women who have been immunized recently with live-attenuated rubella virus vaccine may continue to breastfeed. Secretion of varicella vaccine virus and infection of a breastfeeding infant of a mother who received varicella vaccine has not been noted in the few instances where it has been studied. Varicella vaccine may be considered for a susceptible breastfeeding mother if the risk of exposure to natural varicella-zoster virus is high. Recommendations for use of passive immunization and varicella vaccine for breastfeeding mothers who have had contact with people in whom varicella has developed or for contacts of a breastfeed ing mother in whom varicella has developed are available (see Varicella-Zoster Infections, p 774). Animal experiments have shown that West Nile virus can be transmitted in animal milk, and other related faviviruses can be transmitted to humans via unpasteurized milk from rumi nants. The degree to which West Nile virus is transmitted in human milk and the extent to which breastfeeding infants become infected are unknown. Because the health ben efts of breastfeeding have been established and the risk of West Nile virus transmission through breastfeeding is unknown, women who reside in an area with endemic West Nile virus infection should continue to breastfeed. The potential for transmission of infectious agents through donor human milk requires appropriate selection and screening of donors and careful collec tion, processing, and storage of milk. These policies require docu mentation, counseling, and observation of the affected infant for signs of infection and potential testing of the source mother for infections that could be transmitted via human milk. Recommendations for management of a situation involving an accidental expo sure may be found at Discuss inadvertent administration of the donor milk with the parent(s) of the recipient infant. Collection of milk from the birth mother of a preterm infant does not require processing if fed to her infant, but proper collection and storage procedures should be followed. Microbiologic quality stan dards for fresh, unpasteurized, expressed milk are not available. The presence of gram negative bacteria, S aureus, or alpha or beta-hemolytic streptococci may preclude use of expressed human milk. Routine culture of milk that a birth mother provides to her own infant is not warranted. Although these drugs may appear in milk, the potential risk to an infant must be weighed against the known benefts of continued breastfeeding. As a general guideline, an antimicrobial agent is safe to administer to a lactating woman if it is safe to administer to an infant. Only in rare cases will interruption of breastfeeding be necessary because of maternal medications. The amount of drug an infant receives from a lactating mother depends on a number of factors, including maternal dose, frequency and duration of administration, absorp tion, timing of medication administration and breastfeeding, and distribution characteris tics of the drug. When a lactating woman receives appropriate doses of an antimicrobial agent, the concentration of the compound in her milk usually is less than the equivalent of a therapeutic dose for the infant. A breastfed infant who requires antimicrobial therapy should receive the recommended doses, independent of administration of the agent to the mother. Data for drugs, including antimicrobial agents, administered to lactating women are provided in several categories, including maternal and infant drug levels, effects in breastfed infants, possible effects on lactation, the category into which the drug has been placed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, alternative drugs to consider, and references. Prevention and control of infection in out-of-home child care set tings is infuenced by several factors, including the following: (1) health status, practice of personal hygiene, and immunization status of care providers; (2) environmental sanitation; (3) food-handling procedures; (4) age and immunization status of chil dren; (5) ratio of children to care providers; (6) physical space and quality of facilities; (7) frequency of use of antimicrobial agents in children in child care; and (8) adherence to standard precautions for infection control. Adequately addressing problems of infec tion control in child care settings requires collaborative efforts of public health offcials, licensing agencies, child care providers, physicians, nurses, parents, employers, and other members of the community. Child care programs should require that all enrollees and staff members receive age appropriate immunizations and routine health care. In addition, these programs have the opportunity to provide parents with ongoing instruction in child development, hygiene, appropriate nutrition, and management of minor illnesses. Many early education and child care programs have access to health consultants who can assist providers and par ents with these issues ( Classifcation of Care Service Child care services commonly are classifed by the type of setting, number of children in care, and age and health status of the children. Small family child care homes provide care and education for up to 6 children simultaneously, including any preschool aged relatives of the care provider, in a residence that usually is the home of the care provider. Large family child care homes provide care and education for between 7 and 12 children at a time, including any preschool-aged relatives of the care provider, in a residence that usually is the home of one of the care providers. A child care center is a facility that provides care and education to any number of children in a nonresidential setting or to 13 or more children in any setting if the facility is open on a regular basis. A facility for ill children provides care for 1 or more children who are excluded tempo rarily from their regular child care setting for health reasons. A facility for children with special needs provides specialized care and education for 1 child or more who cannot be accommodated in a setting with typically developing children. All 50 states regulate out of-home child care; however, regulation enforcement is directed toward center-based child care; few states or municipalities license or enforce regulations as carefully for small or large child care homes. Grouping of children by age varies, but in child care centers, common groups consist of infants (birth through 12 months of age), toddlers (13 through 35 months of age), preschoolers (36 through 59 months of age), and school-aged children (5 through 12 years of age). Infants and toddlers who require diapering or assistance in using a toilet have signifcant hands-on contact with care providers. Furthermore, they have oral contact with the environment, have poor control over their secretions and excretions, and have immunity to fewer common pathogens. Toddlers also have frequent direct contact with each other and with secretions of other toddlers. Therefore, child care programs that provide infant and toddler care should be vigilant about practice of infection-control measures. Management and Prevention of Illness Modes of transmission of bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi within child care settings are listed in Table 2. In most instances, the risk of introducing an infectious agent into a child care group is related directly to prevalence of the agent in the population and to the number of susceptible children in that group. Transmission of an agent within the group depends on the following: (1) characteristics of the organism, such as mode of spread, infective dose, and survival in the environment; (2) frequency of asymptomatic infection or carrier state; and (3) immunity to the respective pathogen. Transmission also can be affected by behaviors of the child care providers, particularly hygienic 1 American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. Children infected in a child care group can transmit organisms not only within the group but also within their households and the community. Appropriate hand hygiene and adherence to immunization recommendations are the most important factors for decreasing transmission of disease in child care settings. Options for management of ill or infected children in child care and for reducing transmission of pathogens include the following: (1) antimicrobial treatment or prophy laxis when appropriate; (2) immunization when appropriate; (3) exclusion of ill or infected children from the facility when appropriate; (4) provision of alternative care at a separate site; (5) cohorting to provide care (eg, segregation of infected children in a group with separate staff and facilities); (6) limiting new admissions; (7) hand hygiene; and (8) closing the facility (a rarely exercised option). Recommendations for controlling spread of specifc infectious agents differ according to the epidemiology of the pathogen (see disease-specifc chapters in Section 3) and characteristics of the setting. Infection-control procedures in child care programs that decrease acquisition and transmission of communicable diseases include: (1) periodic (at least annual) review of facility-maintained child and employee illness records, including current immunization status; (2) hygienic and sanitary procedures for toilet use, toilet training, and diaper chang ing; (3) review and enforcement of hand-hygiene procedures; (4) environmental sanita tion; (5) personal hygiene for children and staff; (6) sanitary preparation and handling of food; (7) communicable disease surveillance and reporting; and (8) appropriate handling of animals in the facility. Policies that include education and implementation of proce dures for full and part-time employees and volunteers as well as exclusion policies aid in control of infectious diseases. Health departments should have plans for responding to reportable and nonreportable communicable diseases in child care programs and should provide training, written information, and technical consultation to child care programs when requested or alerted. Evaluation of the well-being of each child should be per formed by a trained staff member each day as the child enters the site and throughout the day as needed. Most children will not need to be excluded from their usual source of care for mild respiratory tract illnesses, because transmission is likely to have occurred before symptoms developed in the child. Disease may occur as a result of contact with children with asymptomatic infection. Exclusion of sick children and adults from out-of-home child care settings has been recommended when such exclusion could decrease the likelihood of secondary cases. Most states have laws about isolation of people with specifc communicable diseases. General recommendations for exclusion of children in out-of-home care are shown in Table 2. Disease or condition-specifc recommendations for exclusion from out-of home care and management of contacts are shown in Table 2. Most minor illnesses do not constitute a reason for excluding a child from child care unless the illness prevents the child from participating in normal activities, as determined by the child care staff, or the illness requires a need for care that is greater than staff can Table 2. General Recommendations for Exclusion of Children in Out-Of-Home Child Care Symptom(s) Management Illness preventing participation in activities, Exclusion until illness resolves and able to as determined by child care staff participate in activities Illness that requires a need for care that is Exclusion or placement in care environment greater than staff can provide without where appropriate care can be provided, compromising health and safety of others without compromising care of others Severe illness suggested by fever with Medical evaluation and exclusion until behavior changes, lethargy, irritability, symptoms have resolved persistent crying, diffculty breathing, progressive rash with above symptoms Rash with fever or behavioral change Medical evaluation and exclusion until illness is determined not to be communicable Persistent abdominal pain (2 hours or more) Medical evaluation and exclusion until or intermittent abdominal pain associated symptoms have resolved with fever, dehydration, or other systemic signs and symptoms Vomiting 2 or more times in preceding Exclusion until symptoms have resolved, unless 24 hours vomiting is determined to be caused by a non communicable condition and child is able to remain hydrated and participate in activities Diarrhea if stool not contained in diaper. Other Salmonella serotypes do not require negative test results from stool cultures. Local health ordinances may differ with respect to number and timing of specimens. Child care staff and families of enrolled children need to be fully informed about inclusion and exclusion criteria. For most outbreaks of vaccine-preventable illnesses, unvaccinated children should be excluded until they are vaccinated.

Diagnosis in suspected human cases can be made postmortem by either immunofuores cent or immunohistochemical examination of brain tissue symptoms congestive heart failure cheap mentat online amex. Laboratory personnel should be consulted before submission of specimens to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention so that appropriate collection and transport of materials can be arranged symptoms 6 days past ovulation order 60 caps mentat. Very few patients with human rabies have survived medicine 219 buy 60caps mentat fast delivery, even with intensive supportive care medicine wheel native american buy mentat 60 caps mastercard. Since 2004 symptoms herpes buy 60 caps mentat visa, 2 adolescent females and an 8-year-old girl symptoms 9f anxiety order online mentat, all of whom had not received rabies postexposure prophylaxis, survived rabies after receipt of a combination of sedation and intensive medical intervention. Education of children to avoid contact with stray or wild animals is of primary importance. Inadvertent contact of family members and pets with potentially rabid animals, such as raccoons, foxes, coyotes, and skunks, may be decreased by securing garbage and pet food outdoors to decrease attraction of domestic and wild animals. Similarly, chimneys and other poten tial entrances for wildlife, including bats, should be identifed and covered. International travelers to areas with endemic canine rabies should be warned to avoid exposure to stray dogs, and if traveling to an area with enzootic infection where immediate access to medical care and biologic agents is limited, preexposure prophylaxis is indicated. Exposure to rabies results from a break in the skin caused by the teeth of a rabid animal or by contamination of scratches, abra sions, or mucous membranes with saliva or other potentially infectious material, such as neural tissue, from a rabid animal. The decision to immunize a potentially exposed person should be made in consultation with the local health department, which can provide information on risk of rabies in a particular area for each species of animal and in accordance with the guidelines in Table 3. In the United States, all mammals are believed to be susceptible, but bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes are more likely to be infected than are other animals. Coyotes, cattle, dogs, cats, ferrets, and other animals occasionally are infected. Bites of rodents (such as squirrels, mice, and rats) or lagomorphs (rabbits, hares, and pikas) rarely require prophylaxis. Additional factors must be consid ered when deciding whether immunoprophylaxis is indicated. An unprovoked attack may be more suggestive of a rabid animal than a bite that occurs during attempts to feed or handle an animal. Properly immunized dogs, cats, and ferrets have only a minimal chance of developing rabies. Postexposure prophylaxis for rabies is recommended for all people bitten by wild mammalian carnivores or bats or by high-risk domestic animals that may be infected. Postexposure prophylaxis is recommended for people who report an open wound, scratch, 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization is discontinued if immunofuorescent test result for the animal is negative. Because the injury inficted by a bat bite or scratch may be small and not readily evident or the circumstances of contact may preclude accurate recall (eg, a bat in a room of a sleeping person or previously unattended child), prophylaxis may be indicated for situations in which a bat physically is present in the same room if a bite or mucous membrane exposure cannot reliably be excluded, unless prompt testing of the bat has excluded rabies virus infection. Prophylaxis should be initiated as soon as possible after bites by known or suspected rabid animals. Rabies virus transmission after exposure to a human with rabies has not been documented convincingly in the United States, except after tissue or organ transplanta tion from donors who died of unsuspected rabies encephalitis. Casual contact with an infected person (eg, by touching a patient) or contact with noninfectious fuids or tissues (eg, blood or feces) alone does not constitute an exposure and is not an indication for prophylaxis (see Care of Hospital Contacts, below). A dog, cat, or ferret that is suspected of having rabies and has bitten a human should be captured, confned, and observed by a veterinarian for 10 days. Any illness in the animal should be reported immediately to the local health department. Other biting animals that may have exposed a person to rabies should be reported immediately to the local health department. Management of animals depends on the species, the circumstances of the bite, and the epidemiology of rabies in the area. Previous immunization of an animal may not preclude the necessity for euthanasia and testing. Because clinical manifestations of rabies in a wild animal cannot be interpreted reliably, a wild mammal suspected of having rabies should be euthanized at once, and its brain should be examined for evidence of rabies virus infection. The exposed person need not receive prophylaxis if the result of rapid examination of the brain by the direct fuorescent antibody test is negative for rabies virus infection. The immediate objective of postexposure prophylaxis is to prevent virus from entering neural tissue. Prompt and thorough local treatment of all lesions is essential, because virus may remain localized to the area of the bite for a variable time. Quaternary ammonium compounds (such as benzalkonium chloride) no longer are considered supe rior to soap. The need for tetanus prophylaxis and measures to control bacterial infection also should be considered. After wound care is completed, concurrent use of passive and active prophylaxis is optimal, with the exceptions of people who previously have received complete immunization regimens (preexposure or postexposure) with a cell culture vaccine and people who have been immunized with other types of rabies vaccines and previously have had a documented rabies virus-neutralizing antibody titer; these people should receive only vaccine. Prophylaxis should begin as soon as possible after exposure, ideally within 24 hours. However, a delay of several days or more may not com promise effectiveness, and prophylaxis should be initiated if reasonably indicated, regard less of the interval between exposure and initiation of therapy. Physicians can obtain expert coun sel from their local or state health departments. Use of a reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Ideally, an immunization series should be initiated and completed with 1 vaccine product unless serious allergic reactions occur. Clinical studies evaluating effcacy or frequency of adverse reactions when the series is completed with a second product have not been conducted. Serologic testing to docu ment seroconversion after administration of a rabies vaccine series is unnecessary but occasionally has been advised for recipients who may be immunocompromised. Intradermal vaccine is not advised for postexposure prophylaxis in the United States, although for reasons of cost and availability, intradermal regimens are used in some countries. Because virus-neutralizing antibody responses in adults who received vaccine in the gluteal area sometimes have been less than in those who were injected in the del toid muscle, the deltoid site always should be used except in infants and young children, in whom the anterolateral thigh is the appropriate site. In adults, local reactions, such as pain, erythema, and swelling or itching at the injection site, are reported in 15% to 25%, and mild systemic reactions, such as headache, nausea, abdominal pain, muscle aches, and dizziness, are reported in 10% to 20% of recipients. All suspected serious, systemic, neuroparalytic, or anaphylactic reactions to the rabies vaccine should be reported immediately to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (see Reporting of Adverse Events, p 44). Although safety of rabies vaccine during pregnancy has not been studied specifcally in the United States, pregnancy should not be considered a contraindication to use of vaccine after exposure. Inactivated nerve tissue vaccines are not licensed in the United States but are available in many areas of the world. These preparations induce neuroparalytic reactions in 1 in 2000 to 1 in 8000 recipients. Immunization with nerve tissue vaccine should be discontinued if meningeal or neuroparalytic reactions develop. Corticosteroids should be used only for life-threatening reactions, because they increase the risk of rabies in experimentally inoculated animals. As much of the dose as possible should be used to infltrate the wound(s), if present. Passive antibody can inhibit the response to rabies vaccines; therefore, the recommended dose should not be exceeded. Others, such as spelunkers (cavers), who may have frequent exposures to bats and other wildlife, also should be considered for preexposure prophylaxis. The preexposure immunization schedule is three 1-mL intramuscular injections each, given on days 0, 7, and 21 or 28. This series of immunizations has resulted in development of rabies virus-neutralizing antibodies in all people properly immunized. Therefore, routine serologic testing for antibody immediately after primary immunization is not indicated. Serum antibodies usually persist for 2 years or longer after the primary series is administered intramuscularly. Rabies virus neutralizing antibody titers should be determined at 6-month intervals for people at con tinuous risk of infection (rabies research laboratory workers, rabies biologics production workers). Titers should be determined approximately every 2 years for people with risk of frequent exposure (rabies diagnostic laboratory workers, spelunkers/cavers, veterinar ians and staff, animal-control and wildlife workers in rabies-enzootic areas, and all people who frequently handle bats). A single booster dose of vaccine should be administered only as appropriate to maintain adequate antibody concentrations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently specifes complete viral neutralization at a titer 1:5 or greater by the rapid fuorescent-focus inhibition test as acceptable; the World Health Organization specifes 0. A variety of approved public health measures, including immunization of dogs, cats, and ferrets and management of stray dogs and selected wildlife, are used to control rabies in animals. In regions where oral immunization of wildlife with recom-1 binant rabies vaccine is undertaken, the prevalence of rabies among foxes, coyotes, and raccoons may be decreased. Unimmunized dogs, cats, ferrets, or other pets bitten by a known rabid animal should be euthanized immediately. If the owner is unwilling to allow the animal to be euthanized, the animal should be placed in strict isolation for 6 months and immunized 1 month before release. If the exposed animal has been immunized within 1 to 3 years, depending on the vaccine administered and local regulations, the animal should be reimmunized and observed for 45 days. All suspected cases of rabies should be reported promptly to public health authorities. S moniliformis infection (streptobacillary fever or Haverhill fever) is charac terized by fever, rash, and arthritis. There is an abrupt onset of fever, chills, muscle pain, vomiting, headache, and occasionally, lymphadenopathy. A maculopapular or petechial rash develops, predominantly on the extremities including the palms and soles, typically within a few days of fever onset. Nonsuppurative migratory polyarthritis or arthralgia follows in approximately 50% of patients. Complications include soft tissue and solid-organ abscesses, septic arthritis, pneumonia, endocarditis, myocarditis, and meningitis. The case-fatality rate is 7% to 10% in untreated patients, and fatal cases have been reported in young chil dren. With S minus infection (sodoku), a period of initial apparent healing at the site of the bite usually is followed by fever and ulceration at the site, regional lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy, and a distinctive rash of red or purple plaques. The natural habitat of S moniliformis and S minus is the upper respiratory tract of rodents. S moniliformis is transmitted by bites or scratches from or exposure to oral secretions of infected rats (eg, kissing the rodent); other rodents (eg, mice, gerbils, squirrels, weasels) and rodent-eating animals, including cats and dogs, also can transmit the infection. Haverhill fever refers to infection after ingestion of unpasteurized milk, water, or food contaminated with S moniliformis. S moniliformis infection accounts for most cases of rat-bite fever in the United States; S minus infections occur primarily in Asia. The incubation period for S moniliformis usually is 3 to 10 days but can be as long as 3 weeks; for S minus, the incubation period is 7 to 21 days. S minus has not been recovered on artifcial media but can be visualized by darkfeld microscopy in wet mounts of blood, exudate of a lesion, and lymph nodes. S minus can be recovered from blood, lymph nodes, or local lesions by intraperitoneal inoculation of mice or guinea pigs. Initial intravenous penicillin G therapy for 5 to 7 days followed by oral penicillin V for 7 days also has been successful. Doxycycline or streptomycin or gentamicin can be substituted when a patient has a serious allergy to penicillin. Doxycycline should not be given to chil dren younger than 8 years of age unless the benefts of therapy are greater than the risks of dental staining (see Tetracyclines, p 801). Patients with endocarditis should receive intravenous high-dose penicillin G for at least 4 weeks. Because the occurrence of S moniliformis after a rat bite is approximately 10%, some experts recom mend postexposure administration of penicillin. People with frequent rodent exposure should wear gloves and avoid hand-to mouth contact during animal handling. Most infants are infected during the frst year of life, with virtually all having been infected at least once by the second birthday. Signs and symptoms of bronchiolitis may include tachypnea, wheezing, cough, crackles, use of accessory muscles, and nasal faring. Lethargy, irritability, and poor feeding, sometimes accompanied by apneic episodes, may be presenting manifestations in these infants. More serious disease involv ing the lower respiratory tract may develop in older children and adults, especially in immunocompromised patients, the elderly, and in people with cardiopulmonary disease. The virus uses attachment (G) and fusion (F) surface glycoproteins for virus entry; these surface proteins lack neuraminidase and hemagglutinin activities. Numerous genotypes have been identifed in each subgroup, and strains of both subgroups often cir culate concurrently in a community. The clinical and epidemiologic signifcance of strain variation has not been determined, but evidence suggests that antigenic differences may affect susceptibility to infection and that some strains may be more virulent than others. Transmission usually is by direct or close contact with contaminated secretions, which may occur from exposure to large-particle droplets at short distances (typically <3 feet) or fomites. Infection among health care personnel and others may occur by hand to eye or hand to nasal epithelium self-inoculation with contaminated secretions. The period of viral shedding usually is 3 to 8 days, but shedding may last longer, espe cially in young infants and in immunosuppressed people, in whom shedding may continue for as long as 3 to 4 weeks. In chil dren, the sensitivity of these assays in comparison with culture varies between 53% and 96%, with most in the 80% to 90% range.

Mentat 60caps on line. 10 Diagnostic Questions Normal or a Symptom - Traditional Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture.