Clarisse M. Machado, M.D.

- Virology Laboratory

- S?o Paulo Institute of Tropical Medicine

- University of S?o Paulo

- S?o Paulo, Brazil

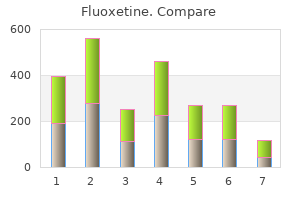

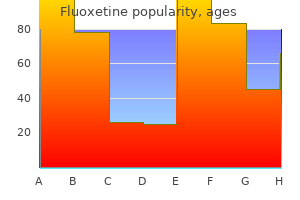

They have also documented the numerous conditions that are associated with cigarette smoking-from pulmonary and heart disease to lung and cervical cancer womens health beaver dam wi order 20 mg fluoxetine amex. Sometimes this is an academic pursuit breast cancer 7000 scratch off discount fluoxetine uk, but more often the goal is to identify a cause so that appropriate public health action might be taken menstrual cycle 5 days late best 10 mg fluoxetine. It has been said that epidemiology can never prove a causal relationship between an exposure and a disease womens health 2013 cheap 10mg fluoxetine overnight delivery. Nevertheless breast cancer definition order fluoxetine 10 mg without a prescription, epidemiology often provides enough information to support effective action women's health center pelham parkway purchase fluoxetine 10 mg with visa. Just as often, epidemiology and laboratory science converge to provide the evidence needed to establish causation. For example, a team of epidemiologists were able to identify a variety of risk factors during an outbreak of a pneumonia among persons attending the American Legion Convention in Philadelphia in 1976. The Epidemiologic Approach Like a newspaper reporter, an epidemiologist determines What, When, Where, Who, and Why. However, the epidemiologist is more likely to describe these concepts in slightly different terms: case definition, time, place, person, and causes. Case Definition A case definition is a set of standard criteria for deciding whether a person has a particular disease or other health-related condition. By using a standard case definition we ensure that every case is diagnosed in the same way, regardless of when or where it occurred, or who identified it. We can then compare the number of cases of the disease that occurred in one time or place with the number that occurred at another time or another place. For example, with a standard case definition, we can compare the number of cases of hepatitis A that occurred in New York City in 1991 with the number that occurred there in 1990. Or we can compare the number of cases that occurred in New York in 1991 with the number that occurred in San Francisco in 1991. With a standard case definition, when we find a difference in disease occurrence, we know it is likely to be a real difference rather than the result of differences in how cases were diagnosed. Appendix C shows case definitions for several diseases of public health importance. A case definition consists of clinical criteria and, sometimes, limitations on time, place, and person. The clinical criteria usually include confirmatory laboratory tests, if available, or combinations of symptoms (subjective complaints), signs (objective physical findings), and other findings. For example, on page 13 see the case definition for rabies that has been excerpted from Appendix C; notice that it requires laboratory confirmation. Compare this with the case definition for Kawasaki syndrome provided in Exercise 1. Kawasaki syndrome is a childhood illness with fever and rash that has no known cause and no specifically distinctive laboratory findings. Notice that its case definition is based on the presence of fever, at least four of five specified clinical findings, and the lack of a more reasonable explanation. A case definition may have several sets of criteria, depending on how certain the diagnosis is. For example, during an outbreak of measles, we might classify a person with a fever and rash as having a suspect, probable, or confirmed case of measles, depending on what additional evidence of measles was present. In other situations, we temporarily classify a case as suspect or probable until laboratory results are available. In the midst of a large outbreak of a disease caused by a known agent, we may permanently classify some cases as suspect or probable, because it is unnecessary and wasteful to run laboratory tests on every patient with a consistent clinical picture and a history of exposure. Case definitions should not rely on laboratory culture results alone, since organisms are sometimes present without causing disease. Case definitions may also vary according to the purpose for classifying the occurrences of a disease. For example, health officials need to know as soon as possible if anyone has symptoms of plague or foodborne botulism so that they can begin planning what actions to take. For such rare but potentially severe communicable diseases, where it is important to identify every possible case, health officials use a sensitive, or ``loose' case definition. On the other hand, investigators of the causes of a disease outbreak want to be certain that any person included in the investigation really had the disease. For instance, in an outbreak of Salmonella agona, the investigators would be more likely to identify the source of the infection if they included only persons who were confirmed to have been infected with that organism, rather than including anyone with acute diarrhea, because some persons may have had diarrhea from a different cause. In this setting, the only disadvantage of a strict case definition is an underestimate of the total number of cases. Numbers and Rates A basic task of a health department is counting cases in order to measure and describe morbidity. When physicians diagnose a case of a reportable disease they send a report of the case to their local health department. These reports are legally required to contain information on time (when the case occurred), place (where the patient lived), and person (the age, race, and sex of the patient). The health department combines the reports and summarizes the information by time, place, and person. From these summaries, the health department determines the extent and patterns of disease occurrence in the area, and identifies clusters or outbreaks of disease. A simple count of cases, however, does not provide all the information a health department needs. To compare the occurrence of a disease at different locations or during different times, a health department converts the case counts into rates, which relate the number of cases to the size of the population where they occurred. With rates, the health department can identify groups in the community with an elevated risk of disease. These so-called high-risk groups can be further assessed and targeted for special intervention; the groups can be studied to identify risk factors that are related to the occurrence of disease. Individuals can use knowledge of these risk factors to guide their decisions about behaviors that influence health. Compiling and analyzing data by time, place, and person is desirable for several reasons. First, the investigator becomes intimately familiar with the data and with the extent of the public health problem being investigated. Second, this provides a detailed description of the health of a population that is easily communicated. Third, such analysis identifies the populations that are at greatest risk of acquiring a particular disease. This information provides important clues to the causes of the disease, and these clues can be turned into testable hypotheses. For example, the seasonal increase of influenza cases with the onset of cold weather is a pattern that is familiar to everyone. By knowing when flu outbreaks will occur, health departments can time their flu shot campaigns effectively. By examining events that precede a disease rate increase or decrease, we may identify causes and appropriate actions to control or prevent further occurrence of the disease. We put the number or rate of cases or deaths on the vertical, y-axis; we put the time periods along the horizontal, x-axis. We often indicate on a graph when events occurred that we believe are related to the particular health problem described in the graph. For example, we may indicate the period of exposure or the date control measures were implemented. Such a graph provides a simple visual depiction of the relative size of a problem, its past trend and potential future course, as well as how other events may have affected the problem. Studying such a graph often gives us insights into what may have caused the problem. Depending on what event we are describing, we may be interested in a period of years or decades, or we may limit the period to days, weeks, or months when the number of cases reported is greater than normal (an epidemic period). For some conditions-for many chronic diseases, for example-we are interested in long-term changes in the number of cases or rate of the condition. For other conditions, we may find it more revealing to look at the occurrence of the condition by season, month, day of the week, or even time of day. For a newly recognized problem, we need to assess the occurrence of the problem over time in a variety of ways until we discover the most appropriate and revealing time period to use. Graphing the annual cases or rate of a disease over a period of years shows long-term or secular trends in the occurrence of the disease. We commonly use these trends to suggest or predict the future incidence of a disease. We also use them in some instances to evaluate programs or policy decisions, or to suggest what caused an increase or decrease in the occurrence of a disease, particularly if the graph indicates when related events took place, as Figure 1. By graphing the occurrence of a disease by week or month over the course of a year or more we can show its seasonal pattern, if any. Some diseases are known to have characteristic seasonal distributions; for example, as mentioned earlier, the number of reported cases of influenza typically increases in winter. Seasonal patterns may suggest hypotheses about how the infection is transmitted, what behavioral factors increase risk, and other possible contributors to the disease or condition. Before reading further, examine the pattern of cases in this graph and decide whether you can conclude from this graph that the disease will have this same pattern every year. Analysis at these shorter time periods is especially important for conditions that are potentially related to occupational or environmental exposures, which may occur at regularly scheduled intervals. One reasonable hypothesis is that farmers spend fewer hours on their tractors on Sundays than on the other days. Examine the pattern of fatalities associated with farm tractor injuries by hour in Figure 1. To show the time course of a disease outbreak or epidemic, we use a specialized graph called an epidemic curve. As with the other graphs you have seen in this section, we place the number of cases on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis. For diseases with longer incubation periods, we might show time in 1-day, 2-day, 3-day, 1-week, or other appropriate intervals. The shape and other features of an epidemic curve can suggest hypotheses about the time and source of exposure, the mode of transmission, and the causative agent. Place We describe a health event by place to gain insight into the geographical extent of the problem. For place, we may use place of residence, birthplace, place of employment, school district, hospital unit, etc. Similarly, we may use large or small geographic units: country, state, county, census tract, street address, map coordinates, or some other standard geographical designation. Sometimes, we may find it useful to analyze data according to place categories such as urban or rural, domestic or foreign, and institutional or noninstitutional. Would it have been more or less useful to analyze the data according to the ``state of residence' of the cases By analyzing the malaria cases by place of acquisition, we can see where the risk of acquiring malaria is high. By analyzing data by place, we can also get an idea of where the agent that causes a disease normally lives and multiplies, what may carry or transmit it, and how it spreads. When we find that the occurrence of a disease is associated with a place, we can infer that factors that increase the risk of the disease are present either in the persons living there (host factors) or in the environment, or both. For example, diseases that are passed from one person to another spread more rapidly in urban areas than in rural ones, mainly because the greater crowding in urban areas provides more opportunities for susceptible people to come into contact with someone who is infected. On the other hand, diseases that are passed from animals to humans often occur in greater numbers in rural and suburban areas because people in those areas are more likely to come into contact with disease-carrying animals, ticks, and the like. For example, perhaps Lyme disease has become more common because people have moved to wooded areas where they come into contact with infected deer ticks. On a map, we can use different shadings, color, or line patterns to indicate how a disease or health event has different numbers or rates of occurrence in different areas, as in Figure 1. We may also label other sites on a spot map, such as where we believe cases may have been exposed, to show the orientation of cases within the area mapped. Study the location of each case in relation to other cases and to the trading pits. Do the location of cases on the spot map lead you to any hypothesis about the source of infection You probably observed that the cases occurred primarily among those working in trading pits #3 and #4. This clustering of illness within trading pits provides indirect evidence that the mumps was transmitted person-to person. Person In descriptive epidemiology, when we organize or analyze data by ``person' there are several person categories available to us. We may use inherent characteristics of people (for example, age, race, sex), their acquired characteristics (immune or marital status), their activities (occupation, leisure activities, use of medications/tobacco/drugs), or the conditions under which they live (socioeconomic status, access to medical care). These categories determine to a large degree who is at greatest risk of experiencing some undesirable health condition, such as becoming infected with a particular disease organism. Depending on what health event we are studying, we may or may not break the data down by the other attributes. Often we analyze data into more than one category simultaneously; for example, we may look at age and sex simultaneously to see if the sexes differ in how they develop a condition that increases with age-as they do for heart disease. Age is probably the single most important ``person' attribute, because almost every health-related event or state varies with age. A number of factors that also vary with age are behind this association: susceptibility, opportunity for exposure, latency or incubation period of the disease, and physiologic response (which affects, among other things, disease development). When we analyze data by age, we try to use age groups that are narrow enough to detect any age-related patterns that may be present in the data. In an initial breakdown by age, we commonly use 5-year age intervals: 0 to 4 years, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, and so on. Sometimes, even the commonly used 5-year age groups can hide important differences.

For people who are allergic to foods pregnancy fashion buy fluoxetine 10 mg amex, insect venom or drugs menopause yeast infections generic fluoxetine 10 mg visa, and for patients at highest risk of anaphylaxis women's health physical therapy purchase fluoxetine 20mg line, the constant fear of suffering an extreme reaction can make living a normal life virtually impossible menstrual exercises fluoxetine 10 mg visa. When a reaction has occurred menstruation irregularities buy cheap fluoxetine 20 mg online, identifying the culprit drug can be a complicated and time-consuming task which is not always performed womens health hershey pa generic fluoxetine 10mg mastercard. Allergens are not listed at all on menus in catering establishments so when eating out, food allergic patients must take extra care to question staff about the ingredients used and the food preparation methods. Other non-allergenic triggers such as tobacco smoke or air pollution can also exacerbate asthma symptoms, so for some patients it is almost impossible to avoid situations which may aggravate their condition. I know this may sound extreme to a lot of people but I would be prepared to lose an arm and a leg if it meant my asthma would go away. These admissions contribute to a total cost of allergy treatment 69 in secondary care of around 56 to 83 million per annum. In addition, there are hidden costs, such as patients with allergies to penicillin being treated with expensive alternative antibiotics; if the drug allergy is wrongly diagnosed, such extra expense is incurred unnecessarily. The precise burden of occupational allergic disorders is not known, partly because it is impossible to quantify the true cost of absence from work or lowered productivity caused by an illness, and because the data on occupational allergic disease are poor (see Chapter 3). What is known is that allergy-related occupational illnesses represent a significant economic burden. Even if patients remain at work, then the symptoms of their disorders are likely to reduce productivity causing a substantial economic burden. The extent to which the indoor environment impacts upon allergic diseases is uncertain. As the development of an allergic condition is not a single, linear process, it is therefore difficult to establish a direct relationship between a particular level of exposure and the development of symptoms. Although the indoor environment may not itself trigger the development of allergy, some factors may exacerbate symptoms and add to the burden for those already suffering from allergic disorders. In addition to biological triggers, various chemicals within the air can also exacerbate the symptoms of asthma. Building Regulations aim to protect the health and safety of people in and around new buildings, but without reference to the occupants. We therefore conclude that there is insufficient evidence to justify the inclusion of low-allergy measures within the Building Regulations at the current time. As chemicals used in the construction industry may play a role in triggering symptoms in some allergic patients, further evaluation of their role is also required in order to inform procurement policies. There is also evidence to suggest that sulphur dioxide 79 can induce the development of asthma 5. Air pollutants may therefore effect both the development and exacerbation of allergic conditions. An important and topical question is whether climate change is increasing the abundance of allergens in the air, such as pollen, which in turn may result in a greater incidence or severity of allergic diseases. There is some evidence that increased atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide fuel the growth of a species of poison ivy, a common cause of contact sensitivity in the United 81 States. In addition, over the last few years global warming has produced milder winters and earlier springs in the United Kingdom, which in turn have 82 caused grass and tree pollen seasons to begin earlier. Thus if levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide continue to rise, this may have serious consequences for allergy sufferers. With the current international interest in climate change, we therefore felt unable to ignore the consequences that climate change policies may have on allergy. The pollutants may have common emission 85 sources and some pollutants affect both climate change and human health. In Chapter 4, we outlined the burden that allergic disorders can place upon children at school. Finally, part of the problem in managing allergic disorders in schools stems from the fact that children themselves generally have a poor understanding of the conditions. However, we are concerned that many teachers and support staff within schools are not appropriately educated in how to deal with allergic emergencies. An example of where staff education is paramount is the administration of adrenaline autoinjectors (such as Epipens or Anapens). The Royal College of Nursing agreed that schools should not be given this responsibility (p 271). We are concerned about the lack of clear guidance regarding the administration of autoinjectors to children with anaphylactic shock in the school environment, and recommend that the Government should review the case for schools holding one or two generic autoinjectors. Although it is difficult to estimate the true number of people who suffer from occupational allergic disorders (see Chapter 3), the prevalence and accompanying burden of occupational allergic conditions has a significant impact upon individual workers and the economy as a whole. The most reliable estimates suggest that the incidence of occupational allergic conditions may be on the decline (para 4. However such a simple solution was not always available for other occupational allergies. Diagnosis of occupational allergic conditions is often delayed due to a lack of education amongst general practitioners (Chapter 9), but once an occupational allergic condition is diagnosed, it is often necessary for the worker to give up their current occupation. However, this scheme provides benefits for all industrial illnesses in a uniform manner and may not necessarily be the best way to help people suffering from occupational allergic conditions. There is therefore a real need to provide the means to support retraining schemes for these workers. We are concerned that employees who are forced to leave work due to an occupational allergic disease can remain unemployed for long periods of time. In Chapter 4, we discussed the burdens of allergic conditions which can touch upon virtually every aspect of daily life. Others face decisions such as what to eat during pregnancy to decrease the chance of an allergic disease developing in the child. However, this statutory legislation only regulates the labelling of allergens that are deliberately added to foods, and does not regulate the labelling of allergens that may unintentionally contaminate foods during production. For the allergic consumer, the everyday task of buying food can therefore present a minefield of potential risks, and may be very costly and time consuming (p 152). Although labelling needs to improve, the root of the problem lies in the actual production of food. We strongly believe that a warning should not be a substitute for controls or for good practice the most important part is to identify where cross-contamination occurs and once that is identified to set up control levels to try to minimise it. The threshold at which a food allergen triggers a reaction varies from one person to another. We recommend that the Food Standards Agency should ensure the needs of food allergic consumers are clearly recognised during the review of food labelling legislation being undertaken by the European Union. For consumers who are already allergic, it is difficult to decide which products are safe to use due to a lack of meaningful terminology used on packaging. We recommend that such products should warn those with a tendency to allergy that they may still get a marked reaction to such products. Most statutory food labelling legislation only applies to prepacked foods, so foods that are sold packaged for direct sale, or those sold loose, are exempt. Whatever measures are taken to minimise the risks of allergen contamination, ultimately some responsibility must lie with the allergic consumer.

Buy fluoxetine 10 mg with amex. Kajol And Mandira Bat For Women’s Health | Bollywood News | ErosNow eBuzz.

It provides spe ci c historical background on how infectious disease is related to concepts of security women's health center baytown order fluoxetine discount, high lights key U breast cancer prayer order fluoxetine now. Chapter Four addresses our second research question related to informa tion needs pregnancy fatigue buy fluoxetine 20mg on-line, summarizing ndings from stakeholder interviews women's health danbury ct fluoxetine 20mg with visa, and Chapter Five addresses the third research question related to the adequacy of current information menstrual 3 times a month fluoxetine 10mg with visa, focusing on the survey of online infectious disease information sources worldwide menopause 12 months cheapest fluoxetine. The link between infectious disease and national security is a relatively new concept. Understanding the challenges of infectious disease threats from this perspective provides a background from which to address our research questions about information needs and the adequacy of currently available information. The rst section in this chapter highlights the toll and challenges of infectious diseases; the second section describes U. Infectious Disease Threats the Toll of Infectious Diseases Approximately a quarter of all deaths in the world today are due to infectious diseases. In the United States, mortality due to infectious diseases decreased over the rst eight decades of the 20th century and then increased between 1981 and 1995 (Armstrong, Conn, and Pinner, 1999). Most experts attribute the declining mortality trends to improved water and sanitation and the introduction and widespread use of vaccines and antibiotics. From 1980 to 1992, the rate of deaths with an underlying infectious disease cause increased 58 percent (Pinner et al. The toll of infectious diseases over the past century can also be appreciated by compar ing the leading causes of death at the beginning and end of the century (see Table 2. In 1900, four of the ten leading causes of death in this country were infectious diseases and col lectively accounted for 31. In 2000, only pneumonia and in uenza, which 5 6 Infectious Disease and National Security: Strategic Information Needs Table 2. With globalization comes the bene ts of increased com merce and closer international relationships, but globalization also presents new challenges and risks. One such challenge is that infectious diseases have followed a trend of increased global travel and spread. Just as infectious diseases are not con ned to their nations of origin and have themselves become global in nature, appropriate responses to contain and control them have become a challenge to nations and require a global approach. While modern means of travel and migration have increased the threat of global disease spread by facilitating disease transmission among people and nations, modern times have also seen advances in the ability to recognize and treat infectious diseases. Prior to the modern technologies that made rapid global travel possible, the geographic spread of infectious diseases was constrained by slower transportation: rst, walking, then 1 It should also be noted that, while the number of deaths caused directly by infectious diseases is signi cant, infectious diseases also contribute to other causes of death, such as cancer. Background: Challenges of and Responses to Infectious Disease Threats 7 travel by animal, then ships and trains. The historic role of travelers (particularly armies, explorers, and merchants) and animals. However, slower transportation and communications during those times also reduced the potential for early warning and response to outbreaks. As ever-faster means of travel have facilitated the spread of infectious disease, modern communications technologies have also presented the opportunity for faster worldwide noti cation of disease outbreaks. Faster noti cation, in turn, presents the opportunity for quicker response to control outbreaks. A critical challenge is to harness the opportunities of modern communications to address the modern challenges of infectious diseases. Today, people can traverse the globe in less time than it takes for many infectious agents to incubate and produce symptoms. Approximately three-fourths of infectious diseases that have emerged and reemerged in recent decades are zoonoses, i. Zoonotic diseases also can be introduced into a human population via agricultural trade, 2 which is a critical element in many national economies worldwide. Such agricultural diseases are beyond the scope of this report, which focuses more speci cally on the threat of diseases directly relevant to humans, including zoonotic diseases. For example, as of this writing, the United States imports approximately 9 million sea shipping containers per year (U. Rapid and unplanned urbanization, particularly in developing countries, poses yet another set of risks for infectious disease transmission. Speci c risk factors include poor sanitation, crowding, and sharing resources such as food and water (Moore, Gould, and Keary, 2003). As Heymann (2003) points out with numerous examples, the modernization of global trade and travel has resulted in the unprecedented emergence of new diseases, the reemergence of known diseases, and growing antimicrobial resistance. Near-Term Infectious Disease Threat: Avian In uenza As of this writing, the H5N1 strain of in uenza (avian in uenza) has raced through bird populations in Asia and into eastern Europe, and has been documented to have jumped to humans in some instances, with 204 o cially reported cases (most of whom had direct contact with infected birds) and 113 deaths in nine countries since 2003. It is widely feared that this virus will adapt su ciently to permit e cient human-to-human transmission, either through mutations or through reassortment with a human in uenza virus, resulting in a novel strain that spreads easily among people. However, multiple interviewees in this study from the importation of wild rodent pets from Ghana into the United States is an example of the former, and the historical spread of bubonic plague by way of rats is an example of the latter. This annual volume re ects an increase of more than 3 million containers since 2001 (Fields, 2002). Of particular concern because of their small size and ubiquity are rats and arthropod vectors of diseases that are transported inadvertently (Lounibos, 2002) and may successfully establish popula tions in new locations (Moore and Mitchell, 1997), sometimes without natural predators or other environmental controls. Background: Challenges of and Responses to Infectious Disease Threats 9 also informed us that there is some evidence that nations are reluctant to report outbreaks of avian in uenza among birds or humans, fearing signi cant economic costs related to preven tive culling of bird ocks and reduced travel and trade. While globalization has changed the world in ways that can foster the spread of infec tious disease, it has also changed traditional concepts of security. Responses to Threats from Infectious Disease Interest in infectious disease surveillance and response increased in the United States and, sub sequently, in the broader world community during the 1990s, probably due to a combination of factors. Response The 1970s and 1980s saw complacency in the United States toward infectious diseases, in part due to a general perception that infectious diseases no longer posed a signi cant risk. Smallpox was eradicated (the last naturally occurring case was in 1977), and other infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, seemed to be controlled. Stewart ever made such a statement in the congressional record, as it is often cited. As more policy attention began to be paid to the potential security threat of global infec tious disease, the U. Global Response Complacency at the global level during the 1970s mirrored that in the United States. Global Infectious Disease Surveillance Global disease surveillance is conducted through a loose framework of formal, informal, and ad hoc arrangements that the U. Historically, surveillance systems have been developed mainly to address speci c diseases. Tose that are targeted for eradication or elimination, such as polio, tend to receive sustained nancial and technical support, while surveillance for other diseases, including emerging diseases, has received limited support (U. The lack of adequate sustained support for surveillance adds to the challenge of control ling emerging diseases. Surveillance systems in all countries su er from a number of common constraints, but these constraints are more prevalent in the poorest countries, where annual per capita expendi ture on all aspects of health care is less than 30 U. The most common constraints are shortages of human and material resources: Trained personnel and laboratory equipment are lacking in many cases (U. Poor coordination of surveillance activities also constrains global disease surveillance. This poor coordination is caused by multiple reporting systems, unclear lines of authority, and incom plete participation by a ected countries (U. General Accounting O ce, 2001), resulting in knowledge gaps about putative outbreaks. Terefore, shortcomings in surveillance reporting of infectious disease seem to exist for two main reasons: Some nations are either unable or unwilling to report. This was the result of a long process and an even longer history of global governance related to infectious diseases. In 1896, the International Sanitary Conference agreed that there was a need for inter national health surveillance (Zacher, 1999). Tat year marked the beginning of cooperative Background: Challenges of and Responses to Infectious Disease Threats 13 surveillance for global infectious disease. Eventually requiring the reporting of plague, cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, relapsing fever, and typhus, the impetus for this agree ment was that Europe feared that these diseases would enter from poorer countries where they were most prevalent (Fidler, 1997). Tese regulations were renamed the International Health Regulations in 1969 and were later revised in 1981. Nations have not always complied (Heymann and Rodier, 1998), fearing the economic consequences of preven tive actions and reduced travel and trade, even though the reporting of outbreaks often triggers international assistance. The revised regulations are aimed to improve global disease detection and control through public health capacity and compliance. Summary Globalization and the modern-day threats of infectious diseases have kept these diseases on the public policy agenda into the 21st century. Recent policy and programming responses by both the United States and the broader global community provide the context from which we examine the three research questions addressed in this study. This chapter begins with a section describing the evolution of this new paradigm, the e ects of infectious disease on security, the implications of a biosecurity policy orientation to natural disease outbreaks, and the implications for global disease reporting. The nal sec tion presents the views of stakeholders we interviewed regarding their perceptions of the link between infectious disease and national security. Infectious Disease and Security Evolving Security Concepts Traditional views of the association between infectious disease and security have often focused on the e ect of health on military success (for example, see Szreter, 2003). In fact, many health discoveries that were made in the course of e orts to protect armies ultimately bene ted other populations as well. Indeed, disease among armies has long been a contributing factor to military outcomes, and warfare has contributed to the spread of dis ease. The association of disease with warfare parallels traditional views of national security, i. Similarly, traditional views of the relationship between disease and security have focused on the threat of disease spreading across borders. However, increasing worldwide attention has recently been paid to a broader issue: the e ect of infectious disease on other concepts of security. Effects of Infectious Disease on Security The discussion of human security versus older, traditional ideas of security is useful in under standing the moral values with which the global community appears to approach the impor tance of health today. However, it remains somewhat intangible, leaving rm associations between health (including infectious disease) and security incompletely de ned. Such assertions are based on a growing body of evidence that associates infec Addressing a New Paradigm: Infectious Disease and National Security 17 tious disease with e ects that may ultimately threaten both human and national concepts of security. Compelling arguments have been made linking infectious disease to conditions that logi cally can a ect security. Tese conditions include those mentioned by Brower and Chalk (2003), and others that have been argued by numerous other authors. The following is a summary of research that has associated speci c e ects of infectious disease with threats to security.

Because licorice root can have the same effect on blood pressure as Florinef womens health boutique purchase 20 mg fluoxetine with visa, combining these two medications should be avoided menstruation 18th century cheap fluoxetine online american express. Common side effects: Some individuals complain of headaches or fatigue after atenolol fsh 80 menopause buy cheap fluoxetine 10mg online, and others have worse lightheadedness or worse symptoms in general menstrual bleeding for 3 weeks discount fluoxetine 10 mg visa. Like other beta-blocker drugs pregnancy 2 buy fluoxetine canada, atenolol can lead to constriction of the airways in individuals with a history of asthma womens health zucchini recipe order generic fluoxetine online. If cough or wheezing develops soon after starting the drug, it may need to be stopped. For those with mild asthma, our impression has been that an inhaled steroid (eg, Pulmicort, Flovent) may allow patients to tolerate the beta-blocker without increased airway reactivity. Atenolol is less likely than other beta-blocker drugs (such as propranolol [Inderal]) to lead to nightmares, confusion, and hallucinations. The activity of the drug can be decreased when it is used in conjunction with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen (Motrin). We recommend that beta blockers be discontinued 2-3 days before surgery because it can interfere with the action of epinephrine if that drug is needed to treat an allergic reaction during surgery. Doses: the usual starting dose of atenolol for older adolescents and adults is 12. For example, an individual weighing 62 kg (136 lb) would likely do well with between 50 and 75 mg of medication per day. People are unlikely to tolerate higher doses if their resting heart rate is below 50 beats per minute. Further study is needed to determine whether patients would do better with one form of beta blocker (selective beta blocker like atenolol) versus another (non-selective beta-blocker like propranolol). By improving constriction of blood vessels in the peripheral circulation, they improve the amount of blood flow returning to the heart. These medications may also exert their beneficial effects through actions on the central nervous system as well. We begin with low doses, increasing once it is clear the patient tolerates the drug. Dextroamphetamine: Dexedrine spansules are the sustained release form of the medication, and because they usually contain no milk protein they are among the ones we use for patients with milk allergy. The average starting dose for adolescents and adults is one 5 mg Dexedrine spansule each morning for 3 days or so. If there is no apparent improvement at this dose by that time, we increase the dose to two of the 5 mg spansules in the morning (at the same time). After another 3-4 days, if there is no improvement, increase to 3 spansules (15 mg) in the morning. The starting dose for school age children as well as adolescents and adults is 5 mg, given first thing in the morning, repeated if necessary 4 hours later. One adolescent, for example, had her best response on a regimen of 15 mg per dose given three times a day. Expected therapeutic effects: the short-acting forms of methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine usually start to take effect after 30-45 minutes or so, and the duration of effect is usually 4 hours or so. If the stimulant medications are working at a particular dose, we expect individuals to feel less lightheadedness, headache, or fatigue. Individuals usually know soon after taking the first few doses if the drug is having a beneficial effect at that dose. The stimulants are controlled substances, so the prescriptions have to be written more frequently, and physicians cannot ask for refills on the same prescription. Side effects: the main side effects of the stimulants are insomnia, a reduction in appetite, moodiness, and occasionally abdominal pain. Some patients describe increased lightheadedness, agitation, and other bothersome symptoms. If these develop, we usually stop the drug and move on to other medication trials. Unlike the stimulant drugs, it is not thought to have direct central nervous system effects. Action: the main effects of midodrine are to cause blood vessels to tighten, thereby reducing the amount of blood that pools in the abdomen and legs, shifting that blood volume into the central circulation where we want it to be. The drug has been used in thousands of individuals around the world, and appears to be well tolerated. Side effects: the main side effects from midodrine in those with orthostatic hypotension (a condition similar to , but not the same as, neurally mediated hypotension) are: high blood pressure when lying down in 15-20%, itching (also called pruritis) in 10-15%, pins and needles sensation in 5-10%, urinary urgency/full bladder in 5%. Common side effects to be expected include a sense of the scalp tingling, and the hair on the arms and neck standing on end. These changes are signs that the drug is working, and are not reasons to discontinue the drug. The first dose should be taken upon awakening in the morning, then 4 hours later, and then 4 hours after that. The drug effect lasts only about 3-4 hours, so the medication may need to be spaced differently once it is clear that it is having a beneficial effect. Comment: As a general rule, midodrine and stimulants should not be prescribed together, as the combination can lead to excessive blood pressure elevations. With Lexapro, the starting dose is 5 mg per day for 2-4 weeks, then increasing to 10 mg per day if needed. Other side effects that can occur include increased bruising, sweating, reduced libido, diarrhea or nausea, or insomnia. One of the recent areas of concern about this class of medications has related to the rare but serious risk of suicide in the first 1-2 weeks after starting these medications. The evidence suggests that this risk is primarily seen in those who are severely depressed. Until mood improves, the individual who remains suicidal has the energy to act upon those impulses. The risk of suicide and major personality changes drops markedly after 2 weeks or so. Be alert to the potential for unusual reactions, and stop the medication and check in with your physicians if you have concerns about how things are going. More data are appearing on these issues, so consult with your health care provider. Side effects: Some individuals complain of headaches or fatigue after Norpace, and others have worse lightheadedness. Other possible side effects are dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, and impaired urination. Norpace should not be taken with erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, phenothiazines, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, cisapride, or other Class 1a anti-arrhythmic agents because of the potential for 20 triggering serious heart rhythm abnormalities. For similar reasons, it should be used with great caution in those on tricyclic antidepressants and ondansetron (Zofran). Use of the drug by those already taking beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers requires similar caution. It is preferable to take it on an empty stomach, an hour before or two hours after eating, but it can be taken with food to reduce stomach irritation. It can lead to an expansion of blood volume in a subset of those with orthostatic intolerance. It is also used as a drug for those with attention deficit disorder, and has been reported to help reduce anxiety, reduce withdrawal symptoms in those who are on narcotic medications, and improve sleep when taken at night. There is also some evidence that it can improve stomach emptying in patients with delayed gastric motility. Side effects: Side effects can include worse fatigue and lightheadedness (due to the anti hypertensive effect), and dry mouth. If side effects are mild in the first week, we usually ask patients to continue the drug to see if these effects resolve and the therapeutic benefit becomes evident over the next few weeks. If people have been taking clonidine for a prolonged period of time, they need to wean off it slowly to avoid developing rebound hypertension. Occasional patients for whom clonidine appeared helpful for several months have developed worse side effects later, consisting of hot flashes, low blood pressure, and worse fatigue. In such instances it is often wise to consider withdrawing clonidine gradually to see whether it is contributing to problems. Comment: For those who are allergic to milk protein the Mylan brand form is lactose free. Its action is to interfere with the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, thereby making more acetylcholine available at nerve and muscle interfaces. Greater concentrations of acetylcholine in the autonomic nervous system would be expected to result in a lower heart rate. Side effects: Mestinon is generally well tolerated, but the most common side effects are nervousness, muscle cramps or twitching, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, stomach cramps, increased saliva, anxiety, and watering eyes. Notify your physician if these are occurring, and if the side effects are more bothersome, stop the drug. The most serious side effects are skin rash, itching, or hives, seizures, trouble breathing, slurred speech, confusion, or irregular heartbeat. Because Mestinon can lower heart rate, it needs to be used with caution (and started at a low dose) in those whose heart rates at rest are in the 50-60 beats per minute range, and in those taking beta-blocker drugs (atenolol, propranolol, metoprolol, and others). The drug can increase bronchial secretions in those with asthma, so it should be taken with caution in affected asthmatics. Magnesium supplements can occasionally cause problems when taking Mestinon, so these should be stopped when Mestinon is started. Some patients may benefit from lower doses of 30 mg once or twice daily, and if a good response is achieved at a low dose, there is no need to increase further. Occasional patients benefit from a third dose during the day (morning, mid-day, bed time), and one adolescent found that 45 mg in the morning, 30 mg at noon and 15 mg at bedtime was ideal for her. Use in pregnancy: Use of pyridostigmine should be avoided during pregnancy due to the possibility of adverse effects on the fetus. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia Chronic orthostatic intolerance: a disorder with discordant cardiac and vascular sympathetic control. Catecholamine response during hemodynamically stable upright posture in individuals with and without tilt-table induced vasovagal syncope. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, and overlapping syndromes. Relationship between neurally mediated hypotension and the chronic fatigue syndrome. Patterns of orthostatic intolerance: the ortho static tachycardia syndrome and adolescent chronic fatigue. The roles of orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic tachycardia, and subnormal erythrocyte volume in the pathogenesis of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Impaired postural cerebral hemodynamics in young patients with chronic fatigue with and without orthostatic intolerance. Usefulness of an abnormal cardiovascular response during low-grade head-up tilt-test for discriminating adolescents with chronic fatigue from healthy controls. Sympathetic predominance of cardiovascular regulation during mild orthostatic stress in adolescents with chronic fatigue. A symposium: A common faint: tailoring treatment for targeted groups with vasovagal syncope. Postural tachycardia syndrome: Reversal of sympathetic hyperresponsiveness and clinical improvement during sodium loading. Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral atenolol in patients with unexplained syncope and positive upright tilt table test results. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral enalapril in patients with neurally mediated syncope. Effects of paroxetine hydrochloride, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on refractory vaso-vagal syncope: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. The use of methylphenidate in the treatment of refractory neurocardiogenic syncope. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition improves tachycardia in postural tachycardia syndrome. Fludrocortisone acetate to treat neurally mediated hypotension in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid based formula. Orthostatic intolerance and chronic fatigue syndrome associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Joint hypermobility is more common in children with chronic fatigue syndrome than in healthy controls. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Treatment of cervical myelopathy in patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome: outcomes and implications.