Eric S. Davidson, MD

- Boston Medical Center, Cardiology Section

- Boston University School of Medicine

- Boston, Massachusetts

Although in broad outline the findings of these different studies are consistent muscle relaxant cz 10 purchase mestinon with visa, there are many differences of detail muscle relaxant 16 discount mestinon 60mg with amex. For example muscle relaxant tizanidine purchase mestinon american express, neither Ainsworth with her one-year-olds nor Maccoby & Feldman with their twoand three-year-olds found sex differences of any magnitude; whereas Lee and his colleagues with their oneand two-year-olds and also Marvin with his twos back spasms 20 weeks pregnant purchase mestinon 60 mg online, threes spasms vitamin deficiency cheap mestinon 60mg online, and fours were struck by the differences between boys and girls muscle relaxant elderly discount mestinon 60mg fast delivery. This and other discrepancies in the results reported in different studies are not easy to interpret. It seems not unlikely that relatively small differences in the arrangements for the testing, for example, in the behaviour of the stranger, can affect considerably the intensity, though not the form, of any behaviour exhibited. From these and other miniature separation experiments certain conclusions can be drawn: a. A child of two years is likely to be almost as upset in these situations as a child of one, and at neither age is he likely to make a quick recovery when rejoined either by mother or by a stranger. A child of three is less likely to be upset in these situations and is more able to understand that mother will soon return. As children get older they are able to use vision and verbal communication as means for keeping in contact with mother; should they become upset when mother leaves the room older children will make more determined attempts to open the door in order to find her. In some studies and at some ages no differences are observed in the behaviour of boys and girls. A further finding from these miniature separation experiments, and one that links with the findings of Shirley (1942) and Heathers (1954) (see pp. These findings emerge from a test-retest study of twenty-four babies tested first at fifty weeks of age and a second time two weeks later. On the assumption that increased sensitivity is not due simply to maturation, which is unlikely, these findings provide the first experimental evidence that at one year of age a separation lasting only a few minutes, in what would ordinarily be regarded as a bland situation, is apt to leave a child more sensitive than he was before to a repetition of the experience. Ontogeny of responses to separation the First Year Since the responses to separation that are so unmistakable in infants of twelve months and older are not present at birth, it is clear that they must develop at some time during the first year of life. Unfortunately, studies designed to throw light on this development are few, and are confined to infants admitted to hospital. It is in keeping, moreover, with what is known about the -52development of attachment behaviour and about cognitive development generally. Development can be summarized as follows: before sixteen weeks differentially directed responses are few in number and are seen only when methods of observation are sensitive; between sixteen and twenty-six weeks differentially directed responses are both more numerous and more apparent; and in the great majority of family infants of six months and over they are plain for all to see. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the full range of responses to separation described in earlier sections of this chapter is not seen before six or seven months of age. Schaffer studied seventy-six infants of various ages under twelve months admitted to hospital: none was marasmic, deformed, or thought to be brain-damaged. While in hospital each child was observed during a two-hour session on each of the first three days (see Schaffer 1958; Schaffer & Callender 1959). Infants were not only without mother but had very little social interaction with nurses. Of the sixteen aged twenty-nine weeks and over, all but one fretted piteously, exhibiting all the struggling, restlessness, and crying so typical of twoand threeyear-olds. Of the nine aged twenty-eight weeks and under, by 1 contrast, all but two are reported to have accepted the situation without protest or fretting: only an unwonted and bewildered silence indicated their awareness of change. Schaffer emphasizes that the shift from a bewildered response to active protest and fretting occurs suddenly and at full intensity at about twenty-eight weeks af age. Thus, of the sixteen infants aged between twenty-nine and fifty-one weeks, both the length of the period of fretting and the intensity of it were as great in those of seven and eight months as in those of eleven and twelve months. Furthermore, responses both to the observers and to mother when she visited changed equally suddenly at about thirty weeks: 1 One of the exceptions was an infant already twenty-eight weeks of age. Infants older than that mostly clung rather desperately to mother, behaviour that was in striking contrast to their negative responses to the observers. The younger infants, by contrast, tended to respond to mother and to observers without showing marked discrimination between them. Similarly, when mother departed, whereas older infants cried loudly and for a long time, even desperately, the younger ones showed no sign of protest. Finally, the behaviour of the infants on their return home from hospital differed greatly according to age-group. Most of the infants aged seven months and over showed intense attachment behaviour. They clung almost continuously to mother, cried loud and long when left alone by her, and were notably afraid of strangers. Even figures formerly familiar, such as father and siblings, were sometimes regarded with suspicion. Infants aged under seven months, by contrast, showed little or no attachment behaviour during their early days at home. On the one hand, these infants seemed utterly 52 preoccupied in scanning the environment; on the other, they seemed unheedful of adults or perhaps averted their head when approached: For hours on end sometimes the infant would crane his neck, scanning his surroundings without apparently focusing on any particular feature and letting his eyes sweep over all objects without attending to any particular one. A completely blank expression was usually observed on his face, though sometimes a bewildered or frightened look was reported. In the extreme form of this syndrome the infants were quite inactive throughout, apart from the scanning behaviour, and -54no vocalization was heard though one or two were reported to have cried or whimpered. To attempts by adults to make contact with them some of these younger infants seemed altogether oblivious. The only way in which the responses of the infants of the two age-groups were similar was in regard to sleep: in infants of both groups disturbed sleep and night-crying were common. It is plain, however, that the responses of these younger infants to separation are very different at every phase from those of older ones, and that it is only after about seven months of age that the patterns that are the subject of this work are to be seen. Only during the second half of the first year, Piaget finds, is there evidence that an infant is beginning to be able to conceive of an object as something that exists independently of himself, in a context of spatial and causal relations, even when it is not present to his perception, and so to search for it when it is missing. Although her results show that a majority of infants develop the capacity in regard to a person earlier than in regard to things, it is not until about the ninth month that the capacity in regard to persons is reasonably well developed, and in a minority it lags some weeks behind that. For reasons to do with cognitive development, therefore, the types of response to separation with which we are concerned could hardly be expected in infants younger than those in whom they are seen. Change after the First Birthday All the evidence suggests that, once established, the typical patterns of response to being placed in strange surroundings -5553 with strange people do not undergo marked change, either in form or in intensity, much before the third birthday. Provided he knows where his mother is and has good reason to expect her to return soon, a child begins to accept another fairly familiar person, even when he is in a fairly unfamiliar place. The only conditions at present known that reduce appreciably the effects of separation from mother are familiar possessions, the companionship of another and familiar child and, as Robertson & Robertson (1971) have shown, especially mothering from a skilled and familiar foster mother. By contrast, strange people, strange places, and strange proceedings are always alarming; and they are especially alarming when encountered alone (see Chapters 7 and 8). These changes are sketched in the first volume (Chapters 11 and 17) and need not be described further here. In so far as attachments to loved figures are an integral part of our lives, a potential to feel distress on separation from them and anxiety at the prospect of separation is so also. Meanwhile, in order that we may view the responses to separation seen in humans in a perspective broader than has been traditional, it is useful to compare the responses of young human children with those of the young of other species. When that is done it becomes evident that, just as attachment behaviour occurs in rather similar forms across a number of mammalian and avian species, so also do responses to separation. Coming nearer man, there are numerous examples in the accounts of monkey and ape infants brought up by human caretakers. All accounts agree on the intensity of protest exhibited whenever a baby primate loses its mother figure, and the intensity of distress that follows when she cannot be found. All agree, too, on the intensity of clinging that occurs after the two are reunited. On such occasions he would more often than not run staggering to the nearest person in sight. By the age of four months, however, the little monkey was exploring increasingly far afield and his master decided to leave him for some hours every day in a cage with other monkeys of his own kind. Although he knew the other monkeys well and was accustomed to play with them he panicked as soon as he knew I wanted to leave him 55 behind, screamed, clung desperately to me and then tried to tear the door open. Afterwards he would cling to me and refuse to leave me out of sight for the rest of the day. In the evening when asleep he would wake up with small shrieks and cling to me, showing all signs of terror when I tried to release his grip. Cathy Hayes (1951) recounts how Viki, a female she adopted at three days, would, when aged four months, cling to her foster mother from the moment she left her crib until she was tucked in at night. If she were on the floor, and I started to get away, she screamed and clung to my leg until I picked her up. The Kelloggs, who did not adopt their female chimp, Gua, until she was seven months old and who kept her for nine months, report identical behaviour (Kellogg & Kellogg 1933). They describe an intensive and tenacious impulse to remain within sight and call of some friend, guardian, or protector. To shut her up in a room by herself, or to walk away faster than she could run, and to leave her behind, proved, as well as we could judge, to be the most awful punishment that could possibly be inflicted. Comparing Gua with their son, who was two and a half months older than she, the Kelloggs report: -58Both subjects displayed what might be called anxious behaviour. This led (in Gua) to an early understanding of the mechanism of door closing and a keen and continual observation of the doors in her vicinity. If she happened to be on one side of a doorway, and her friends on the other, the slightest movement of the door toward closing, whether produced by human hands or by the wind, would bring Gua rushing through the narrowing aperture, crying as she came. The very detailed observations made by van Lawick-Goodall (1968) of chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve in central Africa show not only that anxious and distressed behaviour on being separated, as reported of animals in captivity, occurs also in the wild but that distress at separation continues throughout chimpanzee childhood. During the first year an infant is rarely out of actual contact with mother and, although from its first birthday onwards it spends more time out of contact, it none the less remains in proximity to her. Not until young are four and a half years of age are any of them seen travelling not in the company of mother, and then 1 only rarely. The same sound is used by the mother when she reaches to remove her infant from some potentially dangerous situation or even, on occasion, as she gestures it to cling on when she is ready to go. Another signal used by infants is a scream; it is elicited whenever an infant falls or nearly falls from its mother or is frightened by a sudden loud noise. Indeed, throughout infancy, screaming normally results in the mother hurrying to rescue her child. In each instance, after peering round from various trees, whimpering and screaming as they did so, they hurried off -often in the wrong direction. In one case a juvenile female aged five years lost her mother in the evening and was still whimpering and crying the following morning. In another case, a juvenile stopped screaming before her mother found her, which resulted in a separation lasting several hours. Separations are rare, and usually quickly rectified by vocal signals and mutual search. Early experimental studies these naturalistic accounts show plainly not only that the attachment behaviour of young nonhuman primates is very similar to the attachment behaviour of young children but that their responses to separation are very similar also. Because of this, and because experimental separations lasting longer than minutes are inadmissible in the case of human young, more 57 than one scientist has turned to monkey young for experimental subjects. Animals used include infants aged between two and eight months, of five different species, namely four species of macaque (the rhesus, the pigtail, the bonnet, and the Java) and the patas monkey. In the case of rhesus, pigtail, and Java macaques great distress is observed throughout the period of separation itself and, afterwards, there is a very marked tendency to cling to mother and to resist any attempt at a further separation, however brief. In the case of both bonnet macaques and patas monkeys, intense distress is again seen during the first hours after separation, but then it wanes; thereafter activity is less depressed than in the other species of macaque and there is much less disturbance after reunion with mother. The reduction of distress in the bonnet macaques appears to come about in great part because the separated infant receives continuous substitute care from one of the other familiar females in the group. In what follows attention is given to the studies using rhesus and pigtail infants both because their responses appear to resemble more closely those of human infants and because the studies of these species are more numerous and extensive, especially in the case of the rhesus. Those wishing to compare the behaviour of bonnet macaques are referred to the study by Rosenblum & Kaufman (1968; see also Kaufman & Rosenblum 1969); and of patas monkeys to the study by Preston, Baker & Seay (1970). When two infant pigtail monkeys, each reared in a cage alone with mother, were aged respectively five and seven months, the infants and mothers were exchanged on several occasions for periods of no longer than five minutes. Because mother and infant cling tightly to one another separation cannot be achieved with monkeys except by deception or by the exercise of a good deal of force. Jensen & Tolman give a vivid account: Separation of mother and infant monkeys is an extremely stressful event for both mother and infant as well as for the attendants and for all other monkeys within sight or earshot of the experience. The mother becomes ferocious toward attendants and extremely protective of her infant. The baby clings tightly to the mother and to any object which it can -6158 grasp to avoid being held or removed by the attendant. With the baby gone, the mother paces the cage almost constantly, charges the cage occasionally, bites at it, and makes continual attempts to escape. The infant emits high pitched shrill screams intermittently and almost continuously for the period of separation. Other workers have subjected their monkey infants to much longer separations, the periods ranging from six days to as long as four weeks. In the case of pigtail and rhesus infants all observers report extreme and noisy distress during the twentyfour hours or so immediately after separation followed by a quieter period of a week or more during which the infants show little activity or play and, instead, sit hunched up and depressed. In one (Seay, Hansen & Harlow 1962), four rhesus infants, ages ranging from twenty-four to thirty weeks, were kept apart from 1 mother for a period of three weeks. Since mother was in an adjacent cage and only a transparent screen separated the two, each could see and hear the other. Observations were made at regular intervals during the three weeks prior to separation, during the three weeks of separation, and for three weeks following separation. On each occasion two infants, already familiar with each other, were separated simultaneously and, during the period of separation, each infant had free access to the other. Thus throughout the period of separation all four infants had companionship, access to food and water, 1 For an account of attachment behaviour in rhesus monkeys see Volume I, Chapter 11. Until it is about three years of age a young rhesus monkey in the wild remains close to mother. There was much high-pitched screeching and crying, they made numerous attempts to reach mother, including hurling themselves against the screen, and they also scampered in a disoriented way around the cage. Later, when quiet, the infants huddled against the screen in as close proximity to mother as they could get. Throughout the separation period the pairs of separated infants showed little interest in one another and little play, in contrast to the active play between them seen in the three weeks prior to separation and after it was over.

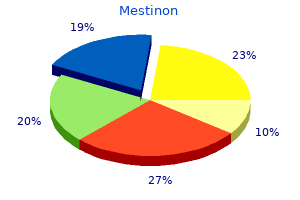

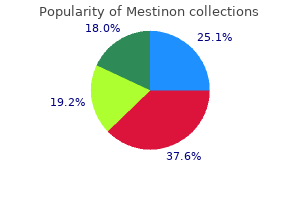

Offer carbamazepine muscle relaxant liver disease generic mestinon 60mg with mastercard, clobazam muscle relaxant hydrochloride mestinon 60mg mastercard, gabapentin spasms in abdomen purchase mestinon canada, lamotrigine muscle relaxant pills purchase mestinon visa, levetiracetam spasms right upper abdomen purchase mestinon 60mg mastercard, oxcarbazepine spasms diaphragm generic mestinon 60 mg, sodium valproate or topiramate as adjunctive treatment to children, young people and adults with focal seizures if firstflline treatments (see recommendations 85 and 86) are ineffective or not tolerated. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 88) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist. DynamicListQuery=&DynamicListSortBy=xCreationDate &DynamicListSortOrder=Desc&DynamicListTitle=&PageNumber=1&Title=Antiepileptics%20&ResultCount=10 fl Estimated cost of a 1500 mg daily dose was fl2. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 63 the Epilepsies Guidance 90. Consider carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine but be aware of the risk of exacerbating myoclonic or absence seizures. Offer ethosuximide or sodium valproate as firstflline treatment to children, young people and adults with absence seizures. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 97) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss with, or fl fl refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist and consider clobazam, clonazepam, levetiracetam, fl fl topiramate or zonisamide. Offer sodium valproate as firstflline treatment to children, young people and adults with newly diagnosed myoclonic seizures, unless it is unsuitable. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 64 the Epilepsies Guidance fl fl 101. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 102) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss fl with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist and consider clobazam, clonazepam, piracetam or fl zonisamide. Offer lamotrigine as adjunctive treatment to children, young people and adults with tonic or atonic seizures if firstflline treatment with sodium valproate is ineffective or not tolerated. Do not offer carbamazepine, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine or vigabatrin. Discuss with, or refer to , a tertiary paediatric epilepsy specialist when an infant presents with infantile spasms. Offer vigabatrin as firstflline treatment to infants with infantile spasms due to tuberous fl sclerosis. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 65 the Epilepsies Guidance 112. Discuss with, or refer to , a tertiary paediatric epilepsy specialist when a child presents with suspected Dravet syndrome. Discuss with a tertiary epilepsy specialist if firstflline treatments (see recommendation 113) in children, young people and adults with Dravet syndrome are ineffective or not tolerated, fl and consider clobazam or stiripentol as adjunctive treatment. Do not offer carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, pregabalin, tiagabine or vigabatrin. Offer carbamazepine or lamotrigine as firstflline treatment to children and young people with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, Panayiotopoulos syndrome or lateflonset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type). Cost taken from the National Health Service Drug Tariff for England and Wales, available at Offer carbamazepine, clobazam, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, sodium valproate or topiramate as adjunctive treatment to children and young people with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, Panayiotopoulos syndrome or lateflonset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type) if firstflline treatments (see recommendations 123 and 124) are ineffective or not tolerated. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 126) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist. Consider topiramate but be aware that it has a less favourable sidefleffect profile than fl sodium valproate and lamotrigine. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 67 the Epilepsies Guidance recommendations 128, 129 and 130) are ineffective or not tolerated. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 131) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss fl with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist and consider clobazam, clonazepam or fl zonisamide. Consider lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or topiramate if sodium valproate is unsuitable or not tolerated. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 136) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss fl with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist and consider clobazam, clonazepam or fl zonisamide. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 68 the Epilepsies Guidance firstflline treatments (see recommendation 139 and 140) are ineffective or not tolerated. Offer ethosuximide or sodium valproate as firstflline treatment to children, young people and adults with absence syndromes. If adjunctive treatment (see recommendation 144) is ineffective or not tolerated, discuss fl with, or refer to , a tertiary epilepsy specialist and consider clobazam, clonazepam, fl fl fl levetiracetam, topiramate or zonisamide. As the treatment pathway progresses, the expertise of an anaesthetist/intensivist should be sought. Give immediate emergency care and treatment to children, young people and adults who have prolonged (lasting 5 minutes or more) or repeated (three or more in an hour) convulsive seizures in the community. Administer buccal midazolam as firstflline treatment in children, young people and adults fl with prolonged or repeated seizures in the community. Administer a maximum of two doses of the firstflline treatment (including preflhospital treatment). Administer intravenous midazolam, propofol or thiopental sodium to treat adults with refractory convulsive status epilepticus. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 70 the Epilepsies Guidance critical life systems support are required. All children, young people and adults with epilepsy should have access via their specialist to a tertiary service when circumstances require. The tertiary service should include a multidisciplinary team, experienced in the assessment of children, young people and adults with complex epilepsy, and have adequate access to investigations and treatment by both medical and surgical means. If seizures are not controlled and/or there is diagnostic uncertainty or treatment failure, fl children, young people and adults should be referred to tertiary services soon for further assessment. In children, the diagnosis and management of epilepsy within the first few years of life may be extremely challenging. Behavioural or developmental regression or inability to identify the epilepsy syndrome in a child, young person or adult should result in immediate referral to tertiary services. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 71 the Epilepsies Guidance 173. Psychiatric coflmorbidity and/or negative baseline investigations should not be a fl contraindication for referral to a tertiary service. They have not been proven to affect seizure frequency and are not an alternative to pharmacological treatment. Psychological interventions (relaxation, cognitive behaviour therapy) may be used in children and young people with drugflresistant focal epilepsy. This includes adults whose epileptic disorder is dominated by focal fl seizures (with or without secondary generalisation) or generalised seizures. This includes children and young people whose fl epileptic disorder is dominated by focal seizures (with or without secondary generalisation) or fl generalised seizures. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 72 the Epilepsies Guidance fl importance of disclosing epilepsy at work, if relevant (if further information or clarification is needed, voluntary organisations should be contacted). The time at which this information should be given will depend on the certainty of the diagnosis, and the need for confirmatory investigations. Adequate time should be set aside in the consultation to provide information, which should be revisited on subsequent consultations. Everyone providing care or treatment for children, young people and adults with epilepsy should be able to provide essential information. The possibility of having seizures should be discussed, and information on epilepsy should be provided before seizures occur, for children, young people and adults at high risk of developing seizures (such as after severe brain injury), with a learning disability, or who have a strong family history of epilepsy. This information should be provided while the child, young person or adult is awaiting a diagnosis and should also be provided to their family and/or carers. Children, young people and adults with epilepsy should be given appropriate information before they make important decisions (for example, regarding pregnancy or employment). In order to enable informed decisions and choice, and to reduce misunderstandings, women and girls with epilepsy and their partners, as appropriate, must be given accurate information and counselling about contraception, conception, pregnancy, caring for children and breastfeeding, and menopause. Information about contraception, conception, pregnancy, or menopause should be given to women and girls in advance of sexual activity, pregnancy or menopause, and the information should be tailored to their individual needs. All healthcare professionals who treat, care for, or support women and girls with epilepsy should be familiar with relevant information and the availability of counselling. Women and girls should be reassured that an increase in seizure frequency is generally unlikely in pregnancy or in the first few months after birth. However, each mother needs to be supported in the choice of feeding method that bests suits her and her family. Specifically discuss the risk of continued use of sodium valproate to the unborn child, being aware that higher doses of sodium valproate (more than 800 mg/day) and polytherapy, particularly with sodium valproate, are associated with greater risk. Discuss with women and girls who are taking lamotrigine that the simultaneous use of any oestrogenflbased contraceptive can result in a significant reduction of lamotrigine levels and lead to loss of seizure control. In women of childbearing potential, the possibility of interaction with oral contraceptives should be discussed and an assessment made as to the risks and benefits of treatment with individual drugs. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 75 the Epilepsies Guidance 215. In girls of childbearing potential, including young girls who are likely to need treatment into their childbearing years, the possibility of interaction with oral contraceptives should be discussed with the child and/or her carer, and an assessment made as to the risks and benefits of treatment with individual drugs. Care of pregnant women and girls should be shared between the obstetrician and the specialist. Women and girls with generalised tonicflclonic seizures should be informed that the fetus may be at relatively higher risk of harm during a seizure, although the absolute risk remains very low, and the level of risk may depend on seizure frequency. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 76 the Epilepsies Guidance fl 229. Parents should be reassured that the risk of injury to the infant caused by maternal seizure is low. Parents of new babies or young children should be informed that introducing a few simple safety precautions may significantly reduce the risk of accidents and minimise anxiety. An approaching birth can be an ideal opportunity to review and consider the best and most helpful measures to start to ensure maximum safety for both mother and baby. Information should be given to all parents about safety precautions to be taken when caring for the baby (see Appendix D). Although there is an increased risk of seizures in children of parents with epilepsy, children, young people and adults with epilepsy should be given information that the probability that a child will be affected is generally low. It is, however, important that there should be regular followflup, planning of delivery, liaison between the specialist or epilepsy team and the obstetrician or midwife. It is important to have an eye witness account supplemented by corroborative evidence (for example, a video account), where possible. Partial Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20 77 the Epilepsies Guidance 245. In the child or young person presenting with epilepsy and learning disability, investigations directed at determining an underlying cause should be undertaken. The recommendations on choice of treatment and the importance of regular monitoring of effectiveness and tolerability are the same for those with learning disabilities as for the general population. Enable children, young people and adults who have learning disabilities, and their family and/or carers where appropriate, to take an active part in developing a personalised care plan for treating their epilepsy while taking into account any comorbidities. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the higher risks of mortality for children, young people and adults with learning disabilities and epilepsy and discuss these with them, their families and/or carers. Attention should be paid to their relationships with family and friends, and at school. Healthcare professionals should adopt a consulting style that allows the young person with epilepsy to participate as a partner in the consultation. Decisions about medication and lifestyle issues should draw on both the expertise of the healthcare professional and the experiences, beliefs and wishes of the young person with epilepsy as well as their family and/or carers. During adolescence a named clinician should assume responsibility for the ongoing management of the young person with epilepsy and ensure smooth transition of care to adult services, and be aware of the need for continuing multiflagency support. The information given to young people should cover epilepsy in general and its diagnosis and treatment, the impact of seizures and adequate seizure control, treatment options including side effects and risks, and the risks of injury. Other important issues to be covered are the possible consequences of epilepsy on lifestyle and future career opportunities and decisions, driving and insurance issues, social security and welfare benefit issues, sudden death and the importance of adherence to medication regimes. Information on lifestyle issues should cover recreational drugs, alcohol, sexual activity and sleep deprivation (see chapter 12). Pay particular attention to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues with polypharmacy and comorbidity in older people with epilepsy. Children, young people and adults from black and minority ethnic groups may have different cultural and communication needs and these should be considered during diagnosis and management.

Order mestinon us. Wasted: Exposing the Family Effect of Addiction | Sam Fowler | TEDxFurmanU.

Picrasma Excelsa (Quassia). Mestinon.

- Dosing considerations for Quassia.

- What other names is Quassia known by?

- Use on the scalp for head lice.

- What is Quassia?

- Appetite loss, indigestion, constipation, fever, intestinal worms, and other conditions.

- Are there safety concerns?

- How does Quassia work?

- Are there any interactions with medications?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96313

Patient should not be restrained in the prone spasms of the larynx buy mestinon american express, face down muscle relaxant bodybuilding buy mestinon cheap online, or hog-tied position as respiratory compromise is a significant risk 3 muscle relaxant rub order mestinon pills in toronto. The patient may have underlying pathology before being tased (refer to appropriate guidelines for managing the underlying medical/traumatic pathology) 4 spasms around heart buy discount mestinon 60 mg on-line. Perform a comprehensive assessment with special attention looking for to signs and symptoms that may indicate agitated delirium 5 spasms prozac purchase mestinon overnight. Transport the patient to the hospital if they have concerning signs or symptoms 6 muscle relaxant for alcoholism buy mestinon 60mg lowest price. Drive Stun is a direct weapon two-point contact which is designed to generate pain and not incapacitate the subject. Only local muscle groups are stimulated with the Drive Stun technique Pertinent Assessment Findings 1. Thoroughly assess the tased patient for trauma as the patient may have fallen from standing or higher 2. Revision Date September 8, 2017 320 Electrical Injuries Aliases Electrical burns, electrocution Patient Care Goals 1. Assess primary survey with specific focus on dysrhythmias or cardiac arrest apply a cardiac monitor 3. Assess for potential associated trauma and note if the patient was thrown from contact point if patient has altered mental status, assume trauma was involved and treat accordingly 5. Assess for potential compartment syndrome from significant extremity tissue damage 6. Administer fluid resuscitation per burn protocol remember that external appearance will underestimate the degree of tissue injury 321 6. Electrical injuries may be associated with significant pain, treat per Pain Management guideline 7. Electrical injury patients should be taken to a burn center whenever possible since these injuries can involve considerable tissue damage 8. When there is significant associated trauma this takes priority, if local trauma resources and burn resources are not in the same facility Patient Safety Considerations 1. Move patient to shelter if electrical storm activity still in area Notes/Educational Pearls Key Considerations 1. Direct tissue damage, altering cell membrane resting potential, and eliciting tetany in skeletal and/or cardiac muscles b. Conversion of electrical energy into thermal energy, causing massive tissue destruction and coagulative necrosis c. Mechanical injury with direct trauma resulting from falls or violent muscle contraction 2. Both types of current can cause involuntary muscle contractions that do not allow the victim to let go of the electrical source iv. However, strong involuntary reactions to shocks in this range may lead to injuries. Recognizing that pain is undertreated in injured patients, it is important to assess whether a patient is experiencing pain 323 o Trauma-02: Pain re-assessment of injured patients. Revision Date September 8, 2017 324 Lightning/Lightning Strike Injury Aliases Lightning burn Patient Care Goals 1. Golf courses, exposed mountains or ledges and farms/fields all present conditions that increase risk of lightning strike, when hazardous meteorological conditions exist 2. Lacking bystander observations or history, it is not always immediately apparent that patient has been the victim of a lightning strike Subtle findings such as injury patterns might suggest lightning injury Inclusion Criteria Patients of all ages who have been the victim of lightning strike injury Exclusion Criteria No recommendations Patient Management Assessment 1. May have secondary traumatic injury as a result of overpressurization, blast or missile injury 8. Assure patent airway if in respiratory arrest only, manage airway as appropriate 2. Consider early pain management for burns or associated traumatic injury [see Pain Management guideline] Patient Safety Considerations 1. Victims do not carry or discharge a current, so the patient is safe to touch and treat Notes/Educational Pearls Key Considerations 1. Lightning strike cardiopulmonary arrest patients have a high rate of successful resuscitation, if initiated early, in contrast to general cardiac arrest statistics 2. If multiple victims, cardiac arrest patients whose injury was witnessed or thought to be recent should be treated first and aggressively (reverse from traditional triage practices) a. Patients suffering cardiac arrest from lightning strike initially suffer a combined cardiac and respiratory arrest b. It may not be immediately apparent that the patient is a lightning strike victim 5. Injury pattern and secondary physical exam findings may be key in identifying patient as a victim of lightning strike 6. Recognizing that pain is undertreated in injured patients, it is important to assess whether a patient is experiencing pain o Trauma-04: Trauma patients transported to trauma center. Investigating a possible new injury mechanism to determine the cause of injuries related to close lightning flashes. Mountain medical mystery: unwitnessed death of a healthy young man, caused by lightning. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of lightning injuries. The lightning heart: a case report and brief review of the cardiovascular complications of lightning injury. Inner ear damage following electric current and lightning injury: a literature review. Injuries, sequelae, and treatment of lightning-induced injuries: 10 years of experience at a Swiss trauma center. Immediate cardiac arrest and subsequent development of cardiogenic shock caused by lightning strike. Author, Reviewer and Staff Information Authors Co-Principal Investigators Carol A. Exclusion Criteria None Toolkit for Key Categories of Data Elements Incident Demographics 1. This information will always apply and be available, even if the responding unit never arrives on scene (is cancelled) or never makes patient contact b. Many systems do not require use of these fields as they can be time-consuming to enter, often too detailed. However, there is some utility in targeted use of these fields for certain situations such as stroke, spinal exams, and trauma without needing to enter all the fields in each record. Many additional factors must be considered when determining capacity including the situation, patient medical history, medical conditions, and consultation with direct medical oversight. Trauma/Injury the exam fields have many useful values for documenting trauma (deformity, bleeding, burns, etc. Use of targeted documentation of injured areas can be helpful, particularly in cases of more serious trauma. Because of the endless possible variations where this could be used, specific fields will not be defined here. Additional Vitals Options All should have a value in the Vitals Date/Time Group and can be documented individually or as an add-on to basic, standard, or full vitals a. Notes/Educational Pearls Documenting Signs and Symptoms Versus Provider Impressions 1. Signs and Symptoms should support the provider impressions, treatment guidelines and overall care given. A symptom is something the patient experiences and tells the provider; it is subjective. Provider impressions should be supported by symptoms but not be the symptoms except on rare occasions where they may be the same. This patient would have possible Symptoms of altered mental status, unconscious, respiratory distress, and respiratory failure/apnea. The narrative summarizes the incident history and care in a manner that is easily digested between caregivers. Specifically, this would include the detailed history of the scene, what the patient may have done or said or other aspects of thecal that only the provider saw, heard, or did. Most training programs provide limited instruction on how to properly document operational and clinical processes, and almost no practice. Most providers learn this skill on the job, and often proficient mentors are sparse. Some more experienced providers use it as they find telling the story from start to finish works best to organize their thoughts. A drawback to this method is that it is easy to forget to include facts because of the lack of structure. It minimizes the likelihood of forgetting information and ensures documentation is consistent between records and providers. Medications Given Showing Positive Action Using Pertinent Negatives 347 For medications that are required by protocol. If a patient had the intended therapeutic response to the medication, but a side effect that caused a clinical deterioration in another body system, then "Improved" should be chosen and the side effects documented as a complication. The patient condition deteriorated or continued to deteriorate because either the medication: i. Had a sub-therapeutic effect that was unable to stop or reverse the decline in patient condition; or iii. Was the wrong medication for the clinical situation and the therapeutic effect caused the condition to worsen. Not Applicable: the nature of the procedure has no direct expected clinical response. An effective procedure that caused an improvement in the patient condition may also have resulted in a procedure complication and the complication should be documented. In the case of worsening condition, documentation of the procedure complications may also be appropriate. Currently there are three versions of the data standard available for documentation and in which data is stored: a. These fields require real data and do not accept Nil (Blank) values, Not Values, or Pertinent Negatives. However, required fields allow Nil (blank) values, Not Values, or Pertinent Negatives to be entered and submitted. Values can be left blank, which can either be an accidental or purposeful omission of data. Value fields can appropriately and purposefully be left blank if there was nothing to enter. There are 11 possible Pertinent Negative values and the available list for each field varies as appropriate to the field. The element numbering structure reflects the dataset and the text group name of the element 5. Some software systems allow the visible text name to be modified or relabeled to meet local standards or nomenclature; this feature can help improve data quality by making documentation easier for the provider. However, the technical structure of the fields has made their practical use limited as all the data is collected as a separate, selfcontained group, rather than as part of the procedures group. However, solutions are currently far from practical, functional, effective, or uniform in how they are being implemented or used across various systems. Reference: Trade names, class, pharmacologic action and contraindications (relative and absolute) information from the website. Additional references include the 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, position statements from the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and the European Association of Poison Control Centers clintox.

Cognitive side-effects of chronic antiepileptic drug treatment: a review of 25 years of research muscle relaxant indications buy cheap mestinon. Adverse reactions to antiepileptic drugs: a multicenter survey of quantitative assessment muscle relaxant generic order mestinon paypal. Living with Epilepsy: looking after yourself: Association of antiepileptic drugs with nontraumatic fractures: a complementary therapies spasms icd 9 code purchase 60 mg mestinon fast delivery. A review of the effect of anticonvulsant medications on bone mineral density and fracture 167 muscle relaxant leg cramps purchase mestinon with visa. A randomized controlled trial of chronic vagus nerve-stimulation and data limitations spasms rib cage buy cheap mestinon 60mg line. Vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy: a meta-analysis of efficacy and predictors of response muscle relaxant end of life purchase 60 mg mestinon overnight delivery. Randomized controlled trial of trigeminal nerve stimulation Edinburgh: the Stationery Office; 1997. Midazolam versus the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for medical diazepam for the treatment of status epilepticus in children and illness. Status epilepticus: its clinical features and treatment in of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue prospective observational study. Cochrane Database Diagnosis and treatment of status epilepticus on a neurological of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 1. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus: causes, therapy, and outcome in 346 patients. A comparison of rectal diazepam gel and placebo for acute treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. Educating lay carers of people with learning disability in epilepsy awareness and in the use of rectal diazepam: 184. Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch a suggested teaching protocol for use by healthcare personnel. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital Health Bull (Edinb) 1999;57(3):198-204. Adverse reactions to new anticonvulsant outcome in barbiturate anesthetic treatment for refractory status drugs. Age-specific incidence and for the residential treatment of seizure exacerbations. Epilepsia prevalence rates of treated epilepsy in an unselected population 2010;51(3):478-82. Buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam for treatment of residential adult patients with serial seizures or status 207. Intranasal midazolam vs rectal diazepam for the home treatment Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer of acute seizures in pediatric patients with epilepsy. Cognitive assessment in the elderly: a Treatment of status epilepticus and acute repetitive seizures with review of clinical methods. Levetiracetam versus lorazepam in research/test-downloads/ status epilepticus: a randomized, open labeled pilot study. Management of refractory status epilepticus at a tertiary care centre in a developing country. Buccal midazolam and rectal diazepam for treatment of prolonged seizures in childhood and 215. New onset geriatric epilepsy: a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Treating repetitive seizures with a rectal diazepam treatment of newly diagnosed epilepsy in the elderly. Topiramate in older patients with partial-onset seizures: a pilot with epilepsy-is it effectivefl Available in senior adults with epilepsy: what we know from randomized from url. The impact of epilepsy on health status among younger among women taking anticonvulsant therapy. Do anticonvulsants reduce the efficacy depression, seizure variables and locus of control on health related of oral contraceptivesfl Pharmacological interventions for epilepsy in people with intellectual disabilities. Interaction between Lamotrigine government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment data/ and a progestin-only contraceptive pill containing desogestrel file/212077/Government Response to the Confidential 75mg (Cerazette). Working Group of the International Association of the Scientific College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2012. Population based, prospective study of the care of women and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American with epilepsy in pregnancy. Prevention of the first occurrence of neuraltube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. Exposure to folic acid antagonists during the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of major malformations. Management of Women with Obesity in supplementation, and congenital abnormalities: a populationPregnancy. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research in-Pregnancy-Guidance. Pre-conceptional vitamin/folic acid supplementation 2007: the of epilepsy in first degree relatives: data from the Italian Episcreen use of folic acid in combination with a multivitamin supplement Study. Genome scan of idiopathic generalized epilepsy: evidence Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment for major susceptibility gene and modifying genes influencing the Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the seizure type. Seizure risk in offspring of individuals with a offspring of women with epilepsy: a prospective study from the history of febrile convulsion. The neonatal coagulation system and and outcome for the child in maternal epilepsy. Pregnancies of women with epilepsy: a population-based study outcome of 179 pregnancies in women with epilepsy. Current management of epilepsy and pregnancy: fetal outcome, congenital malformations, and 304. Cardiac malformations are increased in infants Antiepileptic drug clearance and seizure frequency during of mothers with epilepsy. Foetal outcome in epileptic women with Motor and mental development of infants exposed to antiepileptic seizures during pregnancy. Malformation rates enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom 1994in children of women with untreated epilepsy: a meta-analysis. Levetiracetam concentrations congenital malformations: a joint European prospective study of in serum and in breast milk at birth and during lactation. Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod outcomes in women with epilepsy: a systematic review and metaD, et al. Reviewing maternal deaths to analysis of published pregnancy registries and cohorts. Mawhinney E, Campbell J, Craig J, Russell A, Smithson W, Parsons 2004;63(3):571-3. Valproate and the risk for congenital malformations: Is formulation and dosage regime importantfl Lamotrigine in pregnancy: clearance, therapeutic drug monitoring, and seizure frequency. Population-based study Teratogenicity of the newer antiepileptic drugs the Australian of antiepileptic drug exposure in utero-influence on head experience. J Med Genet Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital 1995;32(9):724-7. Final results from 18 years of the International Lamotrigine Fetal effects of anticonvulsant polytherapies: different risks from Pregnancy Registry. Differential effects of antiepileptic drugs on results of a prospective comparative cohort study. Recurrence risk of congenital malformations in infants topiramate during pregnancy and risk of birth defects. Epilepsia based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report 2010;51(5):805-10. Spina bifida in infants of women treated with outcome of children of women with epilepsy, unexposed or carbamazepine during pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1991;324(10):674exposed prenatally to antiepileptic drugs: a meta-analysis of cohort 7. Does lamotrigine Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to lamotrigine, use in pregnancy increase orofacial cleft risk relative to other sodium valproate and carbamazepine. Available from url: Health Questionnaire-2 and the Neurological Disorders Depression. Identifying depression in epilepsy in a busy clinical setting is enhanced with systematic screening. Topiramate kinetics during delivery, lactation, and in the neonate: preliminary 371. Valproic acid and its metabolites: placental transfer, neonatal pharmacokinetics, 373. A prospective case control study implications of depression in a community population of adults of psychiatric disorders in adults with epilepsy and intellectual with epilepsy. The effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for attention properties of a new measure for use with people with mild deficits in focal seizures: a randomized controlled study. Psychiatric comorbidity, health, apnea in adults and children with epilepsy: a prospective pilot and function in epilepsy. Depression but not seizure frequency predicts quality of life in Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on seizure treatment-resistant epilepsy. Mortality from epilepsy: results from a prospective Clin Neuropharmacol 2004;27(3):133-6. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: terminology and disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised definitions. Ferrer P, Ballarin E, Sabate M, Vidal X, Rottenkolber M, Amelio J, et epilepsy: current knowledge and future directions. Antiepileptic drugs and suicide: a systematic review of adverse 2008;7(11):1021-31. Everyday memory failures in people death in epilepsy: evidence-based analysis of incidence and risk with epilepsy. Seizure memory in epilepsy: transient epileptic amnesia, accelerated control and mortality in epilepsy. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: a series from an epilepsy surgery program and speculation on the relationship 400. Long-term accelerated forgetting of verbal and non-verbal information in temporal lobe epilepsy. Do antiepileptic drugs or generalized tonic-clonic seizure Seizure 1998;7(6):435-46. Unmet needs in patients with epilepsy, following audit, educational intervention and the introduction 424. Prim Health Care Res Dev in epilepsy in patients given adjunctive antiepileptic treatment 2012;13(1):85-91. Risk factors for epilepsy: a controlled prospective study based on coroners cases. Systematic reviews of specialist epilepsy Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy services. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in lamotrigine Available from url. What people with epilepsy want sudden unexplained death in epilepsy: hair analysis at autopsy. Valproate medicines contraindicated in women and girls of childbearing potential unless conditions of Pregnancy Prevention Programme are met. Important issues include misdiagnosis, inappropriate or inadequate treatment, sudden unexpected death that might have been prevented, advice about pregnancy and contraception and management of status epilepticus. Service provision for people with epilepsy has been patchy and sometimes poor both in primary and secondary care. There has been a great increase in the number of epilepsy specialist nurses, and structured services for epilepsy across primary and secondary care are emerging. This guideline is published, therefore, at a time when it is likely to have a major impact. The guidance on the use of the newer antiepileptic drugs confirms their important role in the treatment of epilepsy. Clear guidance is given in various specific areas such as pregnancy and contraception, learning disability, young people, repeated seizures in the community and status epilepticus. The importance of the provision of information for people with epilepsy and their carers is stressed. If there is successful implementation of the recommendations, there will be a great improvement in the care of people with epilepsy. The rights of National Clinical Guideline Centre to be identified as Author of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. PartialPartial PharmacologicalPharmacological UpdateUpdate ofof ClinicalClinical GuidelineGuideline 2020 the Epilepsies Preface the guideline highlighted the inadequacies that existed in the services, care and treatment for people with epilepsy, and made great progress in addressing relevant important issues fl misdiagnosis, inappropriate or inadequate treatment, sudden unexpected death that might have been prevented, advice about pregnancy and contraception and management of status epilepticus. The updated guideline reminds the reader of the need for properly resourced services, offering appropriate levels of expertise, which allow timely access to assessment and treatment for people with epilepsy.