George A. Stouffer, MD

- Henry A Foscue Distinguished

- Professor of Medicine and Cardiology

- Chief of Cardiology for Clinical Affairs

- Division of Cardiology

- University of North Carolina

- Chapel Hill, North Carolina

You should understand the common side effects of the medicine and that common side effects tend to be mild and pass off with time erectile dysfunction heart attack levitra super active 40mg low cost. Knowledge of the serious side effects of your medicine is important erectile dysfunction nervous generic levitra super active 40 mg with amex, along with the realisation that serious side effects of your medicine is important erectile dysfunction doctor in pune cheap 40 mg levitra super active, along with the realisation that serious side effects tend to be uncommon impotence zinc purchase levitra super active 40mg mastercard, but that some serious side effects may be delayed in onset what causes erectile dysfunction cure purchase discount levitra super active on-line, and may only appear after prolonged use of the medicine latest advances in erectile dysfunction treatment cheap 40mg levitra super active visa. Serious side effects that occur early on in the use of a particular medicine usually necessitate stopping the medicine. There is a lot of information about psychotropic medication in the lay press, but much of the reporting is inaccurate or sensational. Inform all doctors who prescribe medicine for you of all the medicines you are taking. Include the medicines on your mood chart, and document benefits and side effects of future reference. Remove mood destabilising chemicals from your life, including alcohol (as completely as possible) and recreational drugs. Stopping and starting medicines can seriously negatively influence the outcome of your condition. Stopping medication because you are "well" has been shown to increase your chance of relapse. Most people who stop medication do so because they are relapsing into another episode. Hospitalisation can be essential to prevent self-destructive behaviour, as well as aggressive and impulsive behaviours, that may have serious consequences that the person will regret. Manic patients often require hospitilisation as they do not recognise they are ill. Research shows that, after their recovery, most manic patients are grateful for the help they received, even if it was against their will at the time. Early recognition and management of mania and depression helps prevent the need for hospitalisation. It is important to recognise that common side effects tend to be mild, and that serious side effects are usually rare. Side effects are dose related and reducing the dose will usually lessen a side effect. Common early side Long-term problems effects you may to watch for-there experience early in are usually treatment, workarounds for depending on dose. Thyroid problems Thirst, drinking Skin problems, fluids and increased especially acne. As such it remains a useful treatment for the most serious forms of depression, especially where there is threat to life, and where other antidepressants have failed to relieve the depression. What to do medication side effects Tell your doctor right away about any side effects you have. These are especially common in high doses and a combination of medicines are needed during the acute phase of treatment. Lowering doses and decreasing the number of medicines usually helps, but some people may have enough side effects to require a change of medicines. Side effects tend to be worse early in the treatment, but some people have taken lithium for 20 years or longer with good results develop problems with side effects or toxicity as they become older. Fortunately, Valproate or carbamazepine are often excellent alternatives as long as the switch is made gradually. If side effects are a problem for you, there are a number of approaches your doctor may suggest:? Trying a different medicine to see if there are fewer or less bothersome side effects. About one in three people with 18 bipolar disorder will be completely free of symptoms by taking mood stabilising medication for life. Most people experience a great reduction in how often they become ill or in the severity of each episode. Always report changes to your doctor immediately, because adjustments in your medicine at the first warning signs can usually restore a normal mood. Sometimes it just takes a slight increase in the blood level of your mood stabiliser, or other medicines may need to be added. Medication adjustments are usually a routine part of treatment (just as insulin doses are changed from time to time in diabetes). Stopping them, even after many years of good health, can lead to disastrous relapse, sometimes within a few months. Generally, the only times you should seriously think of stopping preventive medication are if you want to become pregnant or have a serious medical problem that would make the medicine unsafe. Be sure to discuss all your concerns and any discomforts with the doctor, therapist and family. Symptoms that come back after stopping medication are sometimes much harder to treat. You and your doctor can work together to find the best and most comfortable medicine or you. Successful management of bipolar disorder requires a great deal from patients and families. There will almost certainly be many times when you will be sorely tempted to stop your medication because 1) you feel fine, 2) you miss the highs or 3) you are bothered by side effects. There is a well studied model of bipolar disorder that suggests that each episode worsens your chances of having a smooth long term course. Counselling plays an important adjunctive role in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Therapy issues include dealing with the psychosocial stressors that may precipitate or worsen manic and depressive episodes and dealing with the individual, interpersonal, social and occupational consequences of the disorder itself. Types of psychotherapy Three types of psychotherapy appear to be particularly useful: Behavioural therapy focuses on behaviours that can increase or decrease stress and on ways to increase pleasurable experiences that may help improve depressive symptoms. Cognitive therapy focuses on identifying and changing the pessimistic thoughts and beliefs that can lead to depression. Interpersonal therapy focuses on reducing the strain that a mood disorder may place on relationships. Psychotherapy can be individual (only you and a therapist), group (with other people with similar problems), or family. During treatment psychotherapy usually works more gradually than medication and may take two more to show its full effects. Remember that people can react differently to psychotherapy, just as they do the medicine. Marital therapy and counselling for children in affected families may also be of value. Once the acute episode is over, long-term psychotherapy can help maintain stability and prevent further episodes, but cannot replace ling-term preventive treatment with medication. Since bipolar disorder is a lifetime condition (like many other medical disorders such as diabetes), it is essential the you and your family or others close you learn all about it and its treatment. Go to bed around the same time each night and get up about the same time each morning. Disrupted sleep patterns appear to cause chemical changes in your body that can trigger mood episodes. If you have to take a trip where you ill change time zones and might have jet lag, get advice from your doctor. Do not use alcohol or illicit drugs, these chemicals cause an imbalance in how the brain works. This can, and often does, trigger mood episodes and interferes with your medications. You may sometimes find it tempting to use alcohol or illicit drugs to "treat" your own mood or sleep problems but this almost always makes matters worse. If your gave a problem with substances, as your doctor for help can consider self help groups such as Alcohol Anonymous. Be very careful about "everyday" use of small amounts of alcohol, caffeine and some over-the -counter medications for colds, allergies, or pain. Even small amounts of these substances can interfere with sleep, mood or your medicine. However, you should also realise that it is not always easy to live with someone who has mood swings. If all of you learn as much as possible about bipolar disorder, you will be better able to help reduce the inevitable stress and mutual criticisms that the disorder can cause. Even the "calmest" family will sometimes need outside help in dealing with the stress of a loved one who has continuous symptoms. Ask your doctor or therapist to help educate both of you and your family about bipolar disorder. Of course you want to do your very best at work, but always remember that avoiding relapses is of primary importance and in the long run will increase your overall productivity. Try to keep predictable hours that allow you to get to sleep at a reasonable time. Key recovery concepts Five key recovery concepts provide the foundation for effective recovery. Hope: With good symptoms management, it is possible to experience long periods of wellness. Become an effective advocate for yourself so you can access the services and treatment you need, and make the life you want for yourself. This allows you to make good decisions about all aspects of your treatment and life. Support: While working toward your wellness is up to you, the support of others is essential to maintaining your stability and enhancing the quality of your life. If you are a family or friend of someone with bipolar disorder, become informed about the patient’s illness, its causes, and its treatments. Learn the particular warning signs for how that person acts when he or she is getting manic or depressed. Try to plan, while the person is well, for how you should respond when you see these symptoms. Encourage the patient to stick with the treatment, see the doctor and avoid alcohol and drugs. If the patient has been on a certain treatment for an extended period of time with little improvement in symptoms or has troubling side effects, encourage the person to ask the doctor about other treatments or getting a second opinion. If your loved one becomes ill with a mood episode and suddenly views your concern as interference, remember that this is not a rejection of you-it is the illness talking. Call an ambulance or a hospital emergency room if the 22 situation becomes desperate. Encourage the person to realise that suicidal thinking is a symptom of the illness. With someone prone to manic episodes, take advantages of periods fo stable mood to arrange "advance directives" plans and agreements you make with the person when he or she is stable to try to avoid problems during future episodes of illness. You should discuss and set rules that may involve safeguards such as withholding credit cards, banking privileges and car keys. Just like suicidal depression, uncontrollable manic episodes can be dangerous to patient. When patients are recovering from an episode, let them approach life at their own pace and avoid the extremes of expecting too much or too little. Remember that stabilising the mood is the most important first step towards a full return to function. Try to do things with them, rather than for them so that they are able to regain their sense of self-confidence. Treat people normally once they have recovered, but be alert for telltale symptoms. If there is a recurrence of the illness, you may notice if before the person does. In a caring manner, indicate the early symptoms and suggest a discussion with the doctor. Both you and patient need to tell the difference between a good day and hypomania, and between a bad day and depression. Patients taking medication of bipolar disorder, just like everyone else, do have good days and bad days that are not part of their illness. The production of this booklet has been made possible by the kind generosity of all our sponsors. The views expressed in this booklet reflect the experience of the authors, are not necessarily those of our sponsors. Drugs referred to by the authors should be used only as recommended in the manufacturer’s local data sheets. Bipolar Disorder Advocacy 51 Author and Expert Consultant Disclosures and Contributing Organizations 52 References 55 the information contained in this guide is not intended as, and is not a substitute for, professional medical ParentsMedGuide. Two decades ago, it was rare for a child or adolescent to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Research now suggests that for some, the symptoms of adult bipolar disorder can begin in childhood. However, it is not yet clear how many children and adolescents diagnosed with bipolar disorder will continue to have the disorder as adults. What is very clear is that obtaining a careful clinical assessment is utmost and critical to diagnosing bipolar disorder. During the past decade, the number of children and adolescents diagnosed with bipolar bipolar disorder has increased signifcantly.

He was natural erectile dysfunction pills reviews order levitra super active without a prescription, as she described him erectile dysfunction causes in early 20s order cheap levitra super active line, "very shy but capable of functioning in the world of Community Memory impotence organic origin definition cheapest levitra super active. But the terminals kept breaking down erectile dysfunction va disability compensation order levitra super active 40mg fast delivery, and it became clear that more reliable equipment was essential erectile dysfunction caused by stroke cheap levitra super active 40 mg mastercard. But there was no system waiting in the wings buy generic erectile dysfunction drugs discount 40 mg levitra super active visa, and Community Memory, low in funds and technology, and quickly burning up the store of personal energy of its people, needed something soon. Finally, in 1975, a burned-out group of Community Memory idealists sat down to decide whether to continue the project. But Lee and the others considered it "too risky" to continue the project in its present state. They had too much invested, technically and emotionally, to see the project peter out through a series of frustrated defections and random system crashes. N June 1974, Lee Felsenstein moved into a one-room apartment over a garage in Berkeley. Lee abhorred terminals built to be utterly secure in the face of careless users, black boxes which belch information and are otherwise opaque in their construction. He believed that the people should have a glimpse of what makes the machine go, and the user should be urged to interact in the process. Anything as flexible as computers should inspire people to engage in equally flexible activity. Lee considered the computer itself a model for activism, and hoped the proliferation of computers to people would, in effect, spread the Hacker Ethic throughout society, giving the people power not only over machines but over political oppressors. This inspired Felsenstein to conceive of a tool which would embody the thoughts of Illich, Bucky Fuller, Kari Marx, and Robert Heinlein. Lee dubbed it the Tom Swift Terminal, "in honor of the American folk hero most likely to be found tampering with the equipment. Sitting in the big, wooden, warehouse-like structure that housed Systems Concepts, Lee felt that these guys were not as interested in getting computer technology out to the people as they were in elegant, mind-blowing computer pyrotechnics. He was unconcerned about the high magic they could produce and the exalted pantheon of canonical wizards they revered. He could care less about producing the technological bon mot which Stew was looking for. The twenty miles or so between Palo Alto on the peninsula and San Jose at the lower end of San Francisco Bay had earned the title "Silicon Valley" from the material, made of refined sand, used to make semiconductors. The bosses of these engineers were still pondering the potential uses of the microprocessor. Lee Felsenstein, in any case, was reluctant to take a chance on brand-new technology. His "junk-box" style of engineering precluded using anything but products which he knew would be around for a while. The success of the microchip, and the rapid price-cutting process that occurred after the chips were manufactured in volume (it cost a fortune to design a chip and make a prototype; it cost very little to produce one chip after an assembly line existed to chum them out), resulted in a chip shortage in 1974, and Felsenstein had little confidence that the industry would keep these new microprocessors in sufficient supply for his design. He pictured the users of his terminal treating it the way hackers treat a computer operating system, changing parts and making improvements. So while waiting for clear winners in the microchip race to develop, he took his time, pondering the lessons of Ivan Illich, who favored the design of a tool "that enhances the ability of people to pursue their own goals in their unique way. Felsenstein was only one of hundreds of engineers in the Bay Area who somewhere along the line had shed all pretenses that their interest was solely professional. Soldered into metal boxes, the boards would do strange functions: radio functions, video functions, logic functions. Less important than making these boards perform tasks was the act of making the boards, of creating a system that got something done. But these hackers of hardware would not often confide their objective to outsiders, because, in 1974, the idea of a regular person having a computer in his home was patently absurd. At a counter cluttered with boxes of resistors and switches marked down to pennies, Vinnie the Bear would bargain with the hardware hackers he lovingly referred to as "reclusive cheapskates. Vinnie the Bear, a bearded, big-bellied giant, would pick up the parts you offered for his observations, guess at the possible limits of their uses, wonder if you could pull off a connection with this part or that, and adhere to the legend on the sign above him: "Price Varies as to Attitude of Purchaser. Godbout, a gruff, beefy, still-active pilot who hinted at a past loaded with international espionage and intrigues for government agencies whose names he could not legally utter, would take these parts, throw his own brand name on them, and sell them, often in logic circuitry kits which you could buy by mail order. From his encyclopedic knowledge about what companies were ordering and what they were throwing out, Godbout seemed to know everything going on in the Valley, and as his operation got bigger he supplied more and more parts and kits to eager hardware hackers. But he developed a particularly close relationship with a hardware hacker who had contacted him via the Community Memory terminal before the experiment went into indefinite remission. Marsh, a small, Pancho Villa-moustached man with long dark hair, pale skin, and a tense, ironic way of talking, had left a message for Lee on the terminal asking him if he wanted to get involved in building a project Marsh had read about in a recent issue of Radio Electronics. Marsh had been a hardware freak since childhood; his father had been a radio operator, and he worked on ham sets through school. He majored in engineering at Berkeley,-but got diverted, spending most of his time playing pool. He dropped out, went to Europe, fell in love, and came back to school, but not in engineering it was the sixties, and engineering was extremely uncool, almost right-wing. But he did work in a hi-fi store, selling, fixing, and installing stereos, and he kept working at the store after graduating with a biology degree. Infused with idealism, he wanted to be a teacher of poor kids, but this did not last when he realized that no matter how you cut it, school was regimented students sitting in precise rows, not able to talk. Years of working in the free-flow world of electronics had infused Marsh with the Hacker Ethic, and he saw school as an inefficient, repressive system. Even when he worked at a radical school with an open classroom, he thought it was a sham, still a jail. A friend named Gary Ingram who worked at a company called Dictran got him a job, working on the first digital voltmeter. He never did get it working 100 percent, but the point was doing it, learning about it. He asked Lee to split the $175 garage rent with him, and Lee moved his workbench down there. So Marsh worked on his project, while also cooking up a scheme to buy digital clock parts from Bill Godbout and mount them in fancy wooden cases. It would have a "memory" a place where characters could be stored and that memory would be on a circuit "card," or board. Other cards would get the characters from the keyboard and put characters on the screen. Even if you put a microprocessor on the terminal later on, to do computer-like functions, that powerful chip would be connected to the memory, not running the whole show the task to which microprocessors are accustomed. He was designing as if his brother were still looking over his shoulder, ready to deliver withering sarcasm when the system crashed. But Lee had figured out how the Tom Swift Terminal could extend itself unto eternity. He envisioned it as a system for people to form clubs around, the center of little Tom Swift Terminal karasses of knowledge. It carried on its cover a picture of a machine that would have as big an impact on these people as Lee imagined the Tom Swift Terminal would. It was the brainchild of a strange Floridian running a company in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He was a giant, six feet four and over two hundred and fifty pounds, and his energy and curiosity were awesome. If one day his curiosity was aroused about photography, within a week he would not only own a complete color developing darkroom but be able to talk shop with experts. He sold those in kits, too, and the company took off, expanding to nearly one hundred employees. Around 1974, Ed Roberts would talk often to his boyhood friend from Florida, Eddie Currie, so much so that to keep phone bills down they had taken to exchanging cassette tapes. The tapes became productions in and of themselves, with sound effects, music in the background, and dramatic readings. One day Eddie Currie got this tape from Ed Roberts which was unlike any previous one. Currie later remembered Ed, in the most excited cadences he could muster, speaking of building a computer for the masses. He would use this new microprocessor technology to offer a computer to the world, and it would be so cheap that no one could afford not to buy it. But Roberts was not thinking in small lots, so he "beat Intel over the head" to get the chips for $75 apiece. With that obstacle cleared, he had his staff engineer Bill Yates design a hardware "bus," a setup of connections where points on the chip would be wired to outputs ("pins") which ultimately would support things like a computer memory, and all sorts of peripheral devices. It was an open secret that you could build a computer from one of those chips, but no one had previously dared to do it. Even Intel, which made the chips, thought they were better suited for duty as pieces of traffic-light controllers than as minicomputers. Still, Roberts and Yates worked on the design for the machine, which Bunnell urged Roberts to call "Little Brother" in an Orwellian swipe at the Big Boys. Roberts was confident that people would buy the computer once he offered it in kit form. While Ed Roberts was working on his prototype, a short, balding magazine editor in New York City was thinking along the same lines as Roberts was. Les Solomon was a vagrant from a Bernard Malamud story, a droll, Brooklyn-bom former engineer with a gallows sense of humor. This unremarkable-looking fellow boasted a past as a Zionist mercenary fighting alongside Menachem Begin in Palestine. He would also talk of strange journeys which led him to the feet of South American Indian brujos, or witch doctors, with whom he would partake of ritual drugs and ingest previously sheltered data on the meaning of existence. Popular Electronics, would be in the vanguard of technology and have plenty of weird projects to build. There was another magazine [Radio Electronics], which was also doing digital things. I talked to Ed Roberts, who had published things about his calculators in our magazine, about his computer, and I realized it would be a great project in the magazine. Later on, when coaxed, Les Solomon would speak in hushed terms of the project he was about to introduce to his readers: "The computer is a magic box. Ed Roberts sent him the only prototype via air freight, and it got lost in transit. But, like a totally paralyzed person whose brain was alive, its noncommunicative shell obscured the fact that a computer brain was alive and ticking inside. It was a computer, and what hackers could do with it would be limited only by their own imaginations. In his original brainstorm he had talked about spreading computing to the masses, letting people interact directly with computers, an act that would spread the Hacker Ethic across the land. Before the article came out he would rarely sleep, worrying about possible bankruptcy, forced retirement. The day the magazine reached the subscribers it was clear that there would be no disaster. And there would be hundreds more, hundreds of people across America who had burning desires to build their own computers. Because only weird-type people sit in kitchens and basements and places all hours of the night, soldering things to boards to make machines go flickety flock. About two thousand people, sight unseen, sent checks, money orders, three, four, five hundred dollars apiece, to an unknown company in a relatively unknown city, in a technically unknown state. The weirdos who decided they were going to California, or Oregon, or Christ knows where. What would come out of these systems was not as important as the act of understanding, exploring, and changing the systems themselves the act of creation, the benevolent exercise of power in the logical, unambiguous world of computers, where truth, openness, and democracy existed in a form purer than one could find anywhere else. A year before the Popular Electronics article had come out he had driven up the steep, winding road above Berkeley which leads to the Lawrence Hall of Science, a huge, ominous, bunker-like concrete structure which was the setting for the movie the Forbin Project, about two intelligent computers who collaborate to take over the world. He looked around the exhibits while waiting for his turn on a terminal, and when it was time he stepped into a room with thirty clattering teletypes. He was instantly on the phone to Albuquerque, asking for their catalog, and when he got it, everything looked great the computer kit, the optional disk drives, memory modules, clock modules. He waited that January, he waited that February, and in early March the wait had become so excruciating that he drove down to the airport, got into a plane, flew to Albuquerque, rented a car, and, armed only with the street name, began driving around Albuquerque looking for this computer company. He had been to various firms in Silicon Valley, so he figured he knew what to look for. She was assuring one phone caller after another that yes, one day the computer would come. He had over a million dollars in orders, and plans which were much bigger than that. Every day, it seemed, new things appeared to make it even clearer that the computer revolution had occurred right there. Number three went to the guy in the parking lot who would work with a battery-powered soldering system. It was left to the poor customer to figure out how to put all those bags of junk together. The problem was that, when you were finished, what you had was a box of blinking lights with only 256 bytes of memory. But the Altair, with its incredibly low price and its 8080 chip, was spoken about as if it were the Second Coming. If you are assembling a home computer, school computer, community memory computer.

Order cheap levitra super active on line. ed cure.

Requesting psychologists obtain prior written agreement for all other uses of the data erectile dysfunction at age 31 discount levitra super active 40 mg with visa. Again erectile dysfunction treatments diabetes purchase 40mg levitra super active visa, informed consent means obtaining and documenting people’s agreement to participate in a study impotence journal order levitra super active 40 mg visa, having informed them of everything that might reasonably be expected to afect their decision erectile dysfunction diagnosis cheap levitra super active 40mg without a prescription. This includes details of the procedure diabetes and erectile dysfunction health cheap 40mg levitra super active fast delivery, the risks and benefts of the research erectile dysfunction medication free samples purchase levitra super active from india, the fact that they have the right to decline to participate or to withdraw from the study, the consequences of doing so, and any legal limits to confdentiality. For example, some states require researchers who learn of child abuse or other crimes to report this information to authorities. Although the process of obtaining informed consent often involves having participants read and sign a consent form, it is important to understand that this is not all it is. Although having participants read and sign a consent form might be enough when they are competent adults with the necessary ability and motivation, many participants do not actually read consent forms or read them but do not understand 54 them. For example, participants often mistake consent forms for legal documents and mistakenly believe that by signing them they give up their right to sue the researcher 9 (Mann, 1994). Even with competent adults, therefore, it is good practice to tell participants about the risks and benefts, demonstrate the procedure, ask them if they have questions, and remind them of their right to withdraw at any time—in addition to having them read and sign a consent form. These include situations in which the research is not expected to cause any harm and the procedure is straightforward or the study is conducted in the context of people’s ordinary activities. For example, if you wanted to sit outside a public building and observe whether people hold the door open for people behind them, you would not need to obtain their informed consent. Similarly, if a college instructor wanted to compare two legitimate teaching methods across two sections of his research methods course, he would not need to obtain informed consent from his students. Deception of participants in psychological research can take a variety of forms: misinforming participants about the purpose of a study, using confederates, using phony equipment like Milgram’s shock generator, and presenting participants with false feedback about their performance. Deception also includes not informing participants of the full design or true purpose of the research even if they are not actively misinformed 10 (Sieber, Iannuzzo, & Rodriguez, 1995). For example, a study on incidental learning—learning without conscious efort—might involve having participants read through a list of words in preparation for a “memory test” later. Although participants are likely to assume that the memory test will require them to recall the words, it might instead require them to recall the contents of the room or the appearance of the research assistant. Some researchers have argued that deception of research participants is rarely if ever ethically justifed. Among their arguments are that it prevents participants from giving truly informed consent, fails to respect their dignity as human beings, has the potential to upset them, makes them distrustful and therefore less honest in their responding, and damages the reputation of researchers in the feld (Baumrind, 1985). Informed consent for psychological research: Do subjects comprehend consent forms and understand their legal rights? Compare, for example, Milgram’s study in which he deceived his participants in several signifcant ways that resulted in their experiencing severe psychological stress with an incidental learning study in which a “memory test” turns out to be slightly diferent from what participants were expecting. It also acknowledges that some scientifcally and socially important research questions can be difcult or impossible to answer without deceiving participants. Knowing that a study concerns the extent to which they obey authority, act aggressively toward a peer, or help a stranger is likely to change the way people behave so that the results no longer generalize to the real world. This is the process of informing research participants as soon as possible of the purpose of the study, revealing any deception, and correcting any other misconceptions they might have as a result of participating. For example, an experiment on the efects of being in a sad mood on memory might involve inducing a sad mood in participants by having them think sad thoughts, watch a sad video, or listen to sad music. Debriefng would be the time to return participants’ moods to normal by having them think happy thoughts, watch a happy video, or listen to happy music. Although most contemporary research in psychology does not involve nonhuman animal subjects, a signifcant minority of it does—especially in the study of learning and conditioning, behavioral neuroscience, and the development of drug and surgical therapies for psychological disorders. The use of nonhuman animal subjects in psychological research is like the use of deception in that there are those who argue that it is rarely, if ever, ethically 12 acceptable (Bowd & Shapiro, 1993). Yet they can be subjected to numerous procedures that are likely to cause them sufering. They can be confned, deprived of food and water, subjected to pain, operated on, and ultimately euthanized. When they cannot, they must acquire and care for their subjects humanely and minimize the harm to them. These include the obvious points that researchers must not fabricate data or plagiarize. Proper acknowledgment generally means indicating direct quotations with quotation marks and providing a citation to the source of any quotation or idea used. Researchers should not publish the same data a second time as though it were new, they should share their data with other researchers, and as peer reviewers they should keep the unpublished research they review confdential. Note that the authors’ names on published research—and the order in which those names appear—should refect the importance of each person’s contribution to the research. It would be unethical, for example, to include as an author someone who had made only minor contributions to the research. These codes include the Nuremberg Code, the Declaration of Helsinki, the Belmont Report, and the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. It includes many standards that are relevant mainly to clinical practice, but Standard8concerns informed consent, deception, debriefing, the use of nonhuman animal subjects, and scholarly integrity in research. Although it often involves having them read and sign a consent form, it is not equivalent to reading and signing a consent form. Discussion: In a study on the effects of disgust on moral judgment, participants were asked to judge the morality of disgusting acts, including people eating a dead pet and passionate kissing between a 14 brother and sister (Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993). Describe several strategies for identifying and minimizing risks and deception in psychological research 2. Create thorough informed consent and debriefing procedures, including a consent form. In this section, we look at some practical advice for conducting ethical research in psychology. Again, it is important to remember that ethical issues arise well before you begin to collect data and continue to arise through publication and beyond. If you are conducting research as a course requirement, there may be specifc course standards, policies, and procedures. If any standard, policy, or procedure is unclear—or you are unsure what to do about an ethical issue that arises—you must seek clarifcation. Ultimately, you as the researcher must take responsibility for the ethics of the research you conduct. Start by listing all the risks, including risks of physical and psychological harm and violations of confdentiality. Remember that it is easy for researchers to see risks as less serious than participants do or even to overlook them completely. For example, one student researcher wanted to test people’s sensitivity to violent images by showing them gruesome photographs of crime and accident scenes. Because she was an emergency Chapter 3 59 medical technician, however, she greatly underestimated how disturbing these images were to most people. For example, while most people would have no problem completing a survey about their fear of various crimes, those who have been a victim of one of those crimes might become upset. This is why you should seek input from a variety of people, including your research collaborators, more experienced researchers, and even from nonresearchers who might be better able to take the perspective of a participant. Once you have identifed the risks, you can often reduce or eliminate many of them. For example, you might be able to shorten or simplify the procedure to prevent boredom and frustration. A good example of modifying a research design is a 2009 replication of Milgram’s study conducted by Jerry Burger. Instead of allowing his participants to continue administering shocks up to the 450-V maximum, the researcher always stopped the procedure when they were about to administer the 15 150-V shock (Burger, 2009). This made sense because in Milgram’s study (a) participants’ severe negative reactions occurred after this point and (b) most participants who administered the 150-V shock continued all the way to the 450-V maximum. Thus the researcher was able to compare his results directly with Milgram’s at every point up to the 150-V shock and also was able to estimate how many of his participants would have continued to the maximum—but without subjecting them to the severe stress that Milgram did. For example, you can warn participants that a survey includes questions about their fear of crime and remind them that they are free to withdraw if they think this might upset them. Prescreening can also involve collecting data to identify and eliminate participants. For example, Burger used an extensive prescreening procedure involving multiple questionnaires and an interview with a clinical psychologist to identify and eliminate participants with physical or psychological problems that put them at high risk. You should keep signed consent forms separately from any data that you collect and in such a way that no individual’s name can be linked to his or her data. In addition, beyond people’s sex and age, you should only collect personal information that you actually need to answer your research question. If people’s sexual orientation or ethnicity is not clearly relevant to your research question, for example, then do not ask them about it. Be aware also that certain data collection procedures can lead to unintentional violations of confdentiality. When participants respond to an oral survey in a shopping mall or complete a questionnaire in a classroom setting, it is possible that their responses will be overheard or seen by others. If the responses are personal, it is better to administer the survey or questionnaire individually in private 15. Remember that deception can take a variety of forms, not all of which involve actively misleading participants. Therefore, if your research design includes any form of active deception, you should consider whether it is truly necessary. Imagine, for example, that you want to know whether the age of college professors afects students’ expectations about their teaching ability. You could do this by telling participants that you will show them photos of college professors and ask them to rate each one’s teaching ability. But if the photos are not really of college professors but of your own family members and friends, then this would be deception. This deception could easily be eliminated, however, by telling participants instead to imaginethat the photos are of college professors and to rate them as if they were. In general, it is considered acceptable to wait until debriefng before you reveal your research question as long as you describe the procedure, risks, and benefts during the informed consent process. For example, you would not have to tell participants that you wanted to know whether the age of college professors afects people’s expectations about them until the study was over. Not only is this information unlikely to afect people’s decision about whether or not to participate in the study, but it has the potential to invalidate the results. Participants who know that age is the independent variable might rate the older and younger “professors” diferently because they think you want them to . Alternatively, they might be careful to rate them the same so that they do not appear prejudiced. But even this extremely mild form of deception can be minimized by informing participants—orally, in writing, or both—that although you have accurately described the procedure, risks, and benefts, you will wait to reveal the research question until afterward. In essence, participants give their consent to be deceived or to have information withheld from them until later. Once the risks of the research have been identifed and minimized, you need to weigh them against the benefts. Remember to Chapter 3 61 consider benefts to the research participants, to science, and to society. If you are a student researcher, remember that one of the benefts is the knowledge you will gain about how to conduct scientifc research in psychology—knowledge you can then use to complete your studies and succeed in graduate school or in your career. If the research poses minimal risk—no more than in people’s daily lives or routine physical or psychological examinations—then even a small beneft to participants, science, or society is generally considered enough to justify it. If the research has the potential to upset some participants, for example, then it becomes more important that the study be well designed and answer a scientifcally interesting research question or have clear practical implications. It would be unethical to subject people to pain, fear, or embarrassment for no better reason than to satisfy one’s personal curiosity. In general, psychological research that has the potential to cause harm that is more than minor or lasts for more than a short time is rarely considered justifed by its benefts. Consider, for example, that Milgram’s study—as interesting and important as the results were—would be considered unethical by today’s standards. Once you have settled on a research design, you need to create your informed consent and debriefng procedures. First, when you recruit participants—whether it is through word of mouth, posted advertisements, or a participant pool—provide them with as much information about the study as you can. Second, prepare a script or set of “talking points” to help you explain the study to your participants in simple everyday language. This should include a description of the procedure, the risks and benefts, and their right to withdraw at any time. Your university, department, or course instructor may have a sample consent form that you can adapt for your own study. Remember that if appropriate, both the oral and written parts of the informed consent process should include the fact that you are keeping some information about the design or purpose of the study from them but that you will reveal it during debriefng. Debriefng is similar to informed consent in that you cannot necessarily expect participants to read and understand written debriefng forms. So again it is best to write a script or set of talking points with the goal of being able to explain the study in simple everyday language. During debriefng, you should reveal the research question and full design of the study. For example, if participants are tested under only one condition, then you should explain what happened in the other conditions. If you deceived your participants, you should reveal this as soon as possible, apologize for the deception, explain why it was necessary, and correct any misconceptions that 62 participants might have as a result. Debriefng is also a good time to provide additional benefts to research participants by giving them relevant practical information or referrals to other sources of help. For example, in a study of attitudes toward domestic abuse, you could provide pamphlets about domestic abuse and referral information to the university counseling center for those who might want it. Remember to schedule plenty of time for the informed consent and debriefng processes. The next step is to get institutional approval for your research based on the specifc policies and procedures at your institution or for your course.

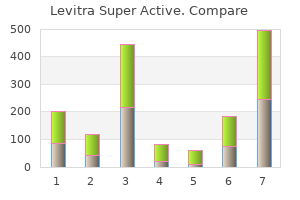

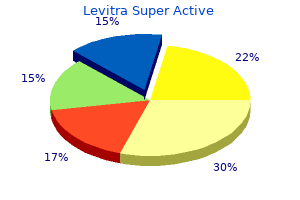

Not long after Lee took over erectile dysfunction treatment honey buy levitra super active mastercard, a troubled Fred Moore resigned his roles as treasurer xatral impotence best levitra super active 40mg, secretary erectile dysfunction medicine reviews 40mg levitra super active visa, and editor of the newsletter erectile dysfunction kaiser discount levitra super active 40mg with mastercard. It was a rough time for him to leave: he felt that the club had been his legacy erectile dysfunction medicine bangladesh order levitra super active without a prescription, in a sense erectile dysfunction protocol purchase discount levitra super active line, but it was probably clear by then that his hopes of it being devoted to public service work were futile. Someone had told Fred about the cheap female labor in Malaysia and other Asian countries who physically assembled those magical chips. He heard how the Asian women were paid pitiful wages, worked in unsafe factories, and were unable to return to their villages, since they never had a chance to leam the traditional modes of cooking or raising a family. He felt he should tell the club about it, force the issue, but by then he realized that it was not the kind of issue that the Homebrew Club was meant to address. Still, he loved the club, and when his personal problems forced him to bow out and go back East, he would later say it was "one of the saddest days of my life. Indeed, each meeting seemed to crackle with spirit and excitement as people swapped gossip and chips, bootstrapping themselves into this new world. At the mapping period, people would stand up and say that they had a problem in setting up this or that part of the Altair, and Lee would ask, "Who can help this guy? Then there would be people standing up to announce the latest rumors in Silicon Valley. Jim Warren, a chunky former Stanford computer science grad student, was a particularly well-connected gossipmonger who would pop up in the random access period and go on for ten minutes about this company and the next, often slipping in some of his personal views on the future of computer communications by digital broadcasts. Another notorious purveyor of this weird form of gossip was a novice engineer named Dan Sokol, who worked as a systems tester at one of the big Valley firms. Sokol, a long-haired, bearded digital disciple who threw himself into Homebrew with the energy of the newly converted, quickly adhered to the Hacker Ethic. He considered no rumor too classified to share, and the more important the secret the greater his delight in its disclosure. Sometimes Sokol, an inveterate barterer, would actually reach into his pocket and produce the prototype of a chip. For instance, one day at work, he recalled, some men from a new company called Atari came in to test some chips. Sokol knew guys at both companies, and they told him the chips were custom parts, laid out and designed by the Atari people. Sokol laid out the design on a circuit board, took it to Homebrew and displayed it. Years earlier, Buckminster Fuller had developed the concept of synergy the collective power, more than the sum of the parts, that comes of people and/or phenomena working together in a system and Homebrew was a textbook example of the concept at work. Or, if someone came up with a clever hack to produce a random number generator on the Altair, he would give out the code so everyone could do it, and by the next meeting someone else would have devised a game that utilized the routine. The synergy would continue even after the meeting, as some of the Homebrew people would carry on their conversations till midnight at the Oasis, a raucous watering hole near the campus. It was just one of dozens of perversely improbable musings that would be not only realized but surpassed within a few years. A tanned, middle-aged baggier with a disarmingly wide smile, he thought that Homebrew was like "having your own little Boy Scout troop, everybody helping everybody else. Not only did he check it out but he came out with a little kit and he put in four or five different parts, oiled it, lubed it, adjusted all the gears. The increasing number of Homebrew members who were designing or giving away new products, from game joysticks to i/o boards for the Altair, used the club as a source of ideas and early orders, and for beta-testing of the prototypes. Whenever a product was done you would bring it to the club, and get the most expert criticism available. Everybody could leam from it, and improve on it if they cared to and were good enough. It was a sizzling atmosphere that worked so well because, in keeping with the Hacker Ethic, no artificial boundaries were maintained. Exploration and hands-on activities were recognized as cardinal values; the information gathered in these explorations and ventures in design were freely distributed even to nominal competitors (the idea of competition came slowly to these new companies, since the struggle was to create a hacker version of an industry a task which took all hands working together); authoritarian rules were disdained, and people believed that personal computers were the ultimate ambassadors of decentralization; the membership ranks were open to anyone wandering in, with respect earned by expertise or good ideas, and it was not unusual to see a seventeen-year-old conversing as an equal with a prosperous, middle-aged veteran engineer; there was a keen level of appreciation of technical elegance and digital artistry; and, above all, these hardware hackers were seeing in a vibrantly different and populist way how computers could change lives. These were cheap machines that they knew were only a few years away from becoming actually useful. This, of course, did not prevent them from becoming totally immersed in hacking these machines for the sake of hacking itself. Their lives were directed to that moment when the board they designed, or the bus they wired, or the program they keyed in would take its first run. You would be jolted with the realization that thousands of computations a second would be flashed through that piece of equipment with your personal stamp on it. Some planners would visit Homebrew and be turned off by the technical ferocity of the discussions, the intense flame that burned brightest when people directed themselves to the hacker pursuit of building. Ted Nelson, author of Computer Lib, came to a meeting and was confused by all of it, later calling the scruffily dressed and largely uncombed Homebrew people "chip-monks, people obsessed with chips. She noted the lack of female hardware hackers, and was enraged at the male hacker obsession with technological play and power. She summed up her feelings with the epithet "the boys and their toys," and like Fred Moore worried that the love affair with technology might blindly lead to abuse of that technology. Yet we had people who knew as much as anyone else knew about this aspect of technology, because it was so new. Solomon first checked on Roger Melen and Harry Garland, who had just finished the prototype of the Cromemco product that would be on the cover of Popular Electronics in November 1975 an add-on board for the Altair which would allow the machine to be connected to a color television set, yielding dazzling graphic results. It was a great moment for Solomon, seeing the computer he had helped bring to the world making a color television set run beautiful patterns. Garland put in a few patterns, and Les Solomon, not fully knowing the rules of the game and certainly not aware of the deep philosophical and mathematical implications, watched the little blue, red, or green stars (that was the way the Dazzler made the cells look) eat the other little stars, or make more stars. One of the stories he would tell, stories so outrageous that only a penny-pincher of the imagination would complain of their improbability, was of the time he was exploring in pursuit of one of his "hobbies," pre-Colombian archeology. This required much time in jungles, "running around with Indians, digging, pitching around in the dirt. Solomon believed that it was the power of vril which enabled the Egyptians to build the pyramids. Solomon had the Homebrew people touch their hands on one of the tables, and he touched it, too. But Lee Felsenstein, seeing another chapter close in that earth shattering science-fiction novel that was his life, understood the mythic impact of this event. They, the soldiers of the Homebrew Computer Club, had taken their talents and applied the Hacker Ethic to work for the common good. It was the act of working together in unison, hands-on, without the doubts caused by holding back, which made extraordinary things occur. If they did not hold back, not retreat within themselves, not yield to the force of greed, they could make the ideals of hackerism ripple through society as if a pearl were dropped in a silver basin. At the heart of the problem was one of the central tenets of the Hacker Ethic: the free flow of information, particularly information that helped fellow hackers understand, explore, and build systems. Previously, there had not been much of a problem in getting that information from others. The "mapping section" time at Homebrew was a good example of that secrets that big institutional companies considered proprietary were often revealed. New hacker-formed companies would give out schematics of their products at Homebrew, not worrying about whether competitors might see them; and after the meetings at the Oasis the young, blue-jeaned officers of the different companies would freely discuss how many boards they shipped, and what new products they were considering. It would give the hardware hackers a hint of the new fragility of the Hacker Ethic. And indicate that as computer power did come to the people other, less altruistic philosophies might prevail. Instead of having to laboriously type in machine language programs onto paper tape and then have to retranslate the signals back (by then many Altair owners had installed i/o cards which would enable them to link the machines to teletypes and paper-tape readers), you would have a way to write quick, useful programs. Since high school the two of them had been hacking computers; large firms paid them to do lucrative contract programming. They had a manual explaining the instruction set for the 8080 chip, and they had the Popular Electronics article with the Altair schematics, so they got to work writing something that would fit in 4K of memory. People were really caught up in this because they were giving computers to people who were so appreciative, and who wanted them so badly. When Paul Alien stuck the tape in the teletype reader and read the tape in, no one was sure what would happen. He hired Alien and arranged to have Gates work from Harvard to help get the thing working. When, not long afterward, Gates finally took off from school (he would never return) to go to Albuquerque, he felt like Picasso stumbling upon a sea of blank canvases here was a neat computer without utilities. Neither Bill Gates nor Ed Roberts believed that software was any kind of sanctified material, meant to be passed around as if it were too holy to pay for. The proper hacker response to competitors was to give them your business plan and technical information, so they might make better products and the world in general might improve. The turnout would largely be people who ordered Altairs and had questions on when they could expect delivery. People who owned them would want to know where they went wrong in assembling the monster. It was connected to a teletype which had a paper-tape reader, and once it was loaded anyone could type in commands and get responses instantly. There is nothing more frustrating to a hacker than to see an extension to a system and not be able to keep hands-on. The thought of going home to an Altair without the capability of that machine running in the pseudo-plush confines of the Rickeys Hyatt must have been like a prison sentence to those hackers. Dan Sokol later recalled that vague "someone" coming up to him and, noting that Sokol worked for one of the semiconductor firms, asking if he had any way of duplicating paper tapes. He had heard a rumor that Gates and Alien had written the interpreter on a big computer system belonging to an institution funded in part by the government, and therefore felt the program belonged to all taxpayers. Why should there be a barrier of ownership standing between a hacker and a tool to explore, improve, and build systems? He ran it all night, churning out tapes, and at the next Homebrew Computer Club meeting he came with a box of tapes. The only stipulation was that if you took a tape, you should make copies and come to the next meeting with two tapes. People snapped up the tapes, and not only brought copies to the next meeting but sent them to other computer clubs as well. There were two hackers, however, who were far from delighted at this demonstration of sharing and cooperation Paul Alien and Bill Gates. Bill Gates was also upset because the version that people were exchanging was loaded with bugs that he was in the process of fixing. Apparently, they were either putting up with the bugs or, more likely, having a grand old hacker time debugging it themselves. So Gates wrote his letter, and Bunnell not only printed it in the Altair newsletter but sent it to other publications, including the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter. Gates went on to explain that this "theft" of software was holding back talented programmers from writing for machines like the Altair. What hobbyist can put 3 man-years into programming, finding all the bugs, documenting his product and distributing for free? The Southern California Computer Society threatened to sue Gates for calling hobbyists "thieves. With the growing number of computers in use (not only Altairs but others as well), a good piece of software became something which could make a lot of money if hackers did not consider it well within their province to pirate the software. No one seemed to object to a software author getting something for his work but neither did the hackers want to let go of the idea that computer programs belonged to everybody. So software could continue being an organic process, with the original author launching the program code on a journey that would see an endless round of improvements. Albrecht complied, running the entire source code, and in a few weeks Altair owners began sending in "bug reports" and suggestions for improvement. But the response was so heavy that he realized an entire new magazine was called for, devoted to software. In addition to several academic degrees, he had about eight years of consulting experience in computers, and was chairman of several special interest groups of the Association for Computer Machinery. He wanted it to be a clearinghouse for assemblers, debuggers, graphics, and music software. Perhaps the most characteristic hacker response to the threat that commercialization might change the spirit of hacking came from an adamantly independent software wizard named Tom Pittman. Pittman was not involved in any of the major projects then in progress around Homebrew. He was representative of the middle-aged hardware hackers who gravitated toward Homebrew and took pride in associating with the microcomputer revolution, but derived so much satisfaction from the personal joys of hacking that they kept their profiles low. Pittman had been going faithfully to Homebrew since the first meeting, and without making much effort to communicate he be came known as one of the purest and most accomplished engineers in the club. He had built an improbably useful computer system based on the relatively low-power Intel 4004 chip, and for a time maintained the Homebrew mailing list on it. He took a perverse pleasure in evoking astonishment from people when he told them what he had done with the system, making it perform tasks far beyond its theoretical limits. Pittman had dreamed of having his own computer since his high school days in the early sixties. All his life he had been a self-described "doer, not a watcher," but he worked alone, in a private world dominated by the reassuring logic of electronics. He would go to the library to take out books on the subject, go through them, then take out more. While the Free Speech Movement was raging around him, Pittman was blithely tangling with the problems in the lab section of the course, systematically wrestling each mathematical conundrum to the ground till it howled for mercy. A sympathetic professor helped him get a job at a Department of Defense laboratory in San Francisco.