Peter E. Andersen, MD

- Professor, Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery

- Professor, Department of Neurosurgery

- Director of Head and Neck Surgery

- Oregon Health and Science University

- Portland, Oregon

Compensated cirrhosis may also progress over time to decompensated cirrhosis associated with ascites arthritis pain back of head buy feldene with visa, oesophageal and gastric varices rheumatoid arthritis zero positive discount feldene 20 mg with mastercard, and eventually to liver failure arthritis pain scale purchase feldene 20 mg without prescription, renal failure and sepsis arthritis vs gout buy cheap feldene 20mg online, all of which are life-threatening arthritis in back symptoms feldene 20 mg with mastercard. The diagnosis of decompensated liver disease is based on both laboratory and clinical assessment arthritis in the knee and running purchase feldene 20 mg with visa, and therefore a careful medical examination of patients must be made before starting treatment. A high-income model of specialist care with a high physician to-patient ratio and availability of advanced laboratory monitoring is not feasible in many countries and therefore service delivery plans need to be adapted accordingly. At present, many countries have poor documentation of the prevalence of infection; this is particularly the case in low-income countries. The Global policy report on the prevention and control of viral hepatitis, 2013 provides country-specifc information on policies and structures already in place to combat viral hepatitis. Estimates of how many people are likely to be affected may be made by assessing populations at high risk as well as previously documented prevalence and incidence rates. A central barrier to treatment roll-out is cost this includes the cost of medicines, taxes, import charges, appropriate medical facilities and staff, as well as diagnostic and monitoring facilities. Negotiation on drug costs is required and prioritization of particular groups, for example, patients with advanced liver disease (? Integration of services, for example, diagnostic and treatment facilities, may help to minimize costs and is likely to facilitate treatment delivery. Task-shifting is the process of sharing clinical management responsibilities with trained personnel such as nurses, clinical offcers and pharmacists. Such personnel should have access to consultations with specialized team members as necessary and are likely to require training in order to facilitate adequate health-care delivery. Sourcing of medication and negotiation on pricing at a central level (using pooled procurement) may also minimize costs. Clinical and laboratory facilities for screening and monitoring patients on treatment are an essential component of health-care provision. The registration of new drugs in individual Member States may be time consuming and will require adequate planning. Service delivery should make use of simplifed operational guidelines, training materials and approaches to clinical decision-making, as well as limited formularies. A psychological assessment at this time and evaluation of potential drug?drug interactions are also essential. Disease education, patient preparation for side-effects while on treatment, support and appropriate informed pre and post-test counselling are required. Such algorithms should include information on when to start therapy, when to stop, follow up, side-effects and management fow sheets. Increased supervision of sites is likely to be important during the early stages of treatment roll-out. This will require political will, fnancial investment, and support from pharmaceutical, medical and civil society organizations around the world. The Secretariat will identify other international conference venues to present the recommendations. The successful implementation of the recommendations in these guidelines will depend on a well-planned and appropriate process of adaptation and integration into relevant regional and national strategies. It is a process that will be determined by available resources, existing enabling policies and practices, and levels of support from partner agencies and organizations. Implementation of these guidelines can be measured by the number of countries that have incorporated them in their national treatment guidelines. Currently, no monitoring system exists that can collect this information on a national level. Viral hepatitis in resource-limited countries and access to antiviral therapies: current and future challenges. Chronic hepatitis C treatment outcomes in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Hepatitis B, C and human immunodefciency virus infections in multiply-injected kala-azar patients in Delhi. The association of health-care use and hepatitis C virus infection in a random sample of urban slum community residents in southern India. Differences in risk factors for being either a hepatitis B carrier or anti-hepatitis C+ in a hepatoma-hyperendemic area in rural Taiwan. High rate of hepatitis C virus infection in an isolated community: persistent hyperendemicity or period-related phenomena? The prevalence and risk factors analysis of serum antibody to hepatitis C virus in the elders in northeast Taiwan. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus from human immunodefciency virus type 1-infected mothers. Seroprevalence of hepatitis virus infection in men who have sex with men aged 18?40 years in Taiwan. Prevalence and sexual risk of hepatitis C virus infection when human immunodefciency virus was acquired through sexual intercourse among patients of the Lyon University Hospitals, France, 1992?2002. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodefciency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: model-based regional estimates. Absence of hepatitis C virus transmission in a prospective cohort of heterosexual serodiscordant couples. A case?control study of risk factors for hepatitis C infection in patients with unexplained routes of infection. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodefciency virus infection. Clinical and virological profles in patients with multiple hepatitis virus infections. Natural course and treatment of dual hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. Performance characteristics and results of a large-scale screening program for viral hepatitis and risk factors associated with exposure to viral hepatitis B and C: results of the National Hepatitis Screening Survey. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment induced viral clearance. Estimation of stage-specifc fbrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Identifcation of unique hepatitis C virus quasispecies in the central nervous system and comparative analysis of internal translational effciency of brain, liver, and serum variants. Liver fbrosis progression in human immunodefciency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. The infuence of human immunodefciency virus coinfection on chronic hepatitis C in injection drug users: a long-term retrospective cohort study. Infuence of human immunodefciency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Causes of death among women with human immunodefciency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Infuence of coinfection with hepatitis C virus on morbidity and mortality due to human immunodefciency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Garcia-Samaniego J, Rodriguez M, Berenguer J, Rodriguez-Rosado R, Carbo J, Asensi V, et al. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Legrand-Abravanel F, Sandres-Saune K, Barange K, Alric L, Moreau J, Desmorat P, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotype 5: epidemiological characteristics and sensitivity to combination therapy with interferon-alpha plus ribavirin. Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 6 infection: response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of peginterferon and ribavirin: implications for clinical effcacy in the treatment of chronic hepaititis C. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus antiviral treatment for injection drug user populations. Hepatitis B and C: ways to promote and offer testing to people at increased risk of infection. Recommendations for the identifcation of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945?1965. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. A 25-year study of the clinical and histologic outcomes of hepatitis C virus infection and its modes of transmission in a cohort of initially asymptomatic blood donors. A retrospective study of hepatitis C virus carriers in a local endemic town in Japan. Current practices of hepatitis C antibody testing and follow-up evaluation in primary care settings: a retrospective study of four large, primary care service centers. Screening for hepatitis C virus in human immunodefciency virus-infected individuals. Infuence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of 3129 heroin users in the frst methadone maintenance treatment clinic in China. Prevalence and risk of blood-borne and sexually transmitted viral infections in incarcerated youth in Salvador, Brazil: opportunity and obligation for intervention. Human immunonodefciency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus: sero-prevalence, co-infection and risk factors among prison inmates in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Outcome of hepatitis C virus infection in Chinese paid plasma donors: a 12?19-year cohort study. Randomized controlled trial of motivational enhancement therapy to reduce alcohol in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Signifcant reductions in drinking following brief alcohol treatment provided in a hepatitis C clinic. An integrated alcohol abuse and medical treatment model for patients with hepatitis C. Hazardous alcohol consumption and other barriers to antiviral treatment among hepatitis C positive people receiving opioid maintenance treatment. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users: Cochrane Review. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fbrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Interferon-alpha treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a meta analytic evaluation. Interferon for interferon nonresponding and relapsing patients with chronic hepatitis C. Antiviral therapy of hepatitis C in chronic kidney diseases: meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Antiviral therapy for prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C: systematic review and meta analysis of randomised controlled trials. Antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C in patients with human immunodefciency virus. Pegylated and non-pegylated interferon-alfa and ribavirin for the treatment of mild chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Outcome of sustained virological responders with histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Real life safety of telaprevir or boceprevir in combination with peginterferon alfa/ribavirin, in cirrhotic non responders. Rodriguez-Torres M, Rodriguez-Orengo J, Gaggar A, Shen G, Symonds B, McHutchison J, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C genotype 1 in patients with unfavorable treatment characteristics: a randomized clinical trial. Assessing the cost effectiveness of treating chronic hepatitis C virus in people who inject drugs in Australia. Hepatitis C treatment for injection drug users: a review of the available evidence. Olysio (simeprevir) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in combination antiviral treatment. Hepatotoxicity associated with protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral regimens with or without concurrent ritonavir. Hepatotoxicity associated with nevirapine or efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy: Role of hepatitis C and B infections. Ribavirin potentiates the effcacy and toxicity of 2`,3` dideoxyinosine in the murine acquired immunodefciency syndrome model. Prevalence and risk factors of asymptomatic hepatitis C virus infection in Egyptian children.

In addition to the cortex best pain relief arthritis knee buy generic feldene 20mg, other parts of the brain arthritis pain ankle discount 20 mg feldene mastercard, including the hippocampus arthritis in dogs what to do purchase 20 mg feldene amex, cerebellum arthritis in neck and lightheadedness purchase feldene 20mg free shipping, and the amygdala arthritis in the feet pictures discount feldene 20mg with visa, are also important in memory arthritis bracelet buy feldene cheap online. Case studies of patients with amnesia can provide information about the brain structures involved in different types of memory. Psychological research has produced a great deal of knowledge about long-term memory, and this research can be useful as you try to learn and remember new material. Ebbinghaus plotted how many of the syllables he could remember against the time that had elapsed since he had studied them. He discovered an important principle of memory: Memory decays rapidly at first, but the amount of decay levels off with time (see Figure 5. Bahrick (1984) found that students who took a Spanish language course forgot about one half of the vocabulary that they had learned within three years, but that after that time their memory remained pretty much constant. This suggests that Hermann Ebbinghaus found that memory for information you should try to review the material you drops off rapidly at first but then levels off after time. Ebbinghaus also discovered another important principle of learning, known as the spacing effect. The spacing effect, also known as distributed practice, refers to improved learning when the same amount of studying is spread out over periods of time, then when it occurs closer together, known as massed practice. This means that you will learn more if you study a little bit every day throughout the semester than if you wait to cram at the last minute (see Figure 5. Ebbinghaus and other researchers have found that overlearning helps encoding (Driskell, Willis, & Copper, 1992). Students frequently think that they have already mastered the material, but then discover when they get to the exam that they have not. Try to keep studying and reviewing, even if you think you already know all the material. If you are having difficulty remembering the spacing effect refers to the fact that memory is better a particular piece of information, it never when it is distributed rather than massed. Leslie, Lee Ann, and Nora all studied for four hours total, but the students who hurts to try using a mnemonic or spread out their learning into smaller study sessions did better memory aid. These techniques are primarily used for simple memorization such as lists and names. Make use of self Material is better recalled if it is Connect new information about memory strategies reference. Be aware of the Information that we have learned Review the material that you have already studied forgetting curve. Make use of the Information is learned better when Study a little bit every day; do not cram at the spacing effect it is studied in shorter periods last minute. Rely on We can continue to learn even Keep studying, even if you think you already have overlearning. Use context We have better retrieval when it If possible, study under conditions similar to dependent occurs in the same situation in the conditions in which you will take the retrieval. Use state We have better retrieval when we Do not study under the influence of drugs or dependent are in the same psychological state alcohol because they will affect your retrieval. Hermann Ebbinghaus made important contributions to the study of memory, including modeling the forgetting curve, the superiority of distributive practice over massed practice, and the benefits of overlearning. In the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the characters undergo a medical procedure designed to erase their memories of a painful romantic relationship. Go to this website to try some memory games illustrating key concepts in this chapter. Review the genetic basis for cognition and disorders at this interactive website: Imagine all of your thoughts as if they were physical entities, swirling rapidly inside your mind. How is it possible that the brain is able to move from one thought to the next in an organized, orderly fashion? The brain is endlessly perceiving, processing, planning, organizing, and remembering; it is always active. Simply put, cognition is thinking, and it encompasses the processes associated with perception, knowledge, problem solving, judgment, language, and memory. Scientists who study cognition are searching for ways to understand how we integrate, organize, and utilize our conscious cognitive experiences without being aware of all of the unconscious work that our brains are doing (Kahneman, 2011). Exceptionally complex, cognition is an essential feature of human consciousness, yet not all aspects of cognition are consciously experienced. Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition She Was Certain, but She Was Wrong: In 1984 Jennifer Thompson was a 22-year-old college student in North Carolina. One night a man broke into her apartment, put a knife to her throat, and raped her. I looked at his hairline; I looked for scars, for tattoos, for anything that would help me identify him. Thompson identified Ronald Cotton as the rapist, and she later testified against him at trial. Consumed by guilt, Thompson sought out Cotton when he was released from prison, and they have since become friends (Innocence Project, n. They fail in part due to our inadequate encoding and storage, and in part due to our inability to accurately retrieve stored information. Memory is also influenced by the setting in which it occurs, by the events that occur to us after we have experienced an event, and by the cognitive processes that we use to help us remember. Cognitive biases are errors in memory or judgment that are caused by the inappropriate use of cognitive processes (see Table 5. The study of cognitive biases is important both because it relates to the important psychological theme of accuracy versus inaccuracy in perception, and because being aware of the types of errors that we may make can help us avoid them and therefore improve our decision-making skills. But research reveals a pervasive cognitive bias toward overconfidence, which is the tendency for people to be too certain about their ability to accurately remember events and to make judgments. Eichenbaum (1999) and Dunning, Griffin, Milojkovic, and Ross (1990) asked college students to predict how another student would react in various situations. Some participants made predictions about a fellow student whom they had just met and interviewed, and others made predictions about their roommates whom they knew very well. Source monitoring the ability to accurately identify the Uncertainty about the source of a source of a memory memory may lead to mistaken judgments. Misinformation Errors in memory that occur when new, Eyewitnesses, based on the questions asked effect but incorrect information influences by the police, may change their memories existing accurate memories of what they observed at the crime scene. Confirmation bias the tendency to verify and confirm our Once beliefs become established, they existing memories rather than to become self-perpetuating and difficult to challenge and disconfirm them change. Functional fixedness When schemas prevent us from seeing Creativity may be impaired by the overuse and using information in new and of traditional, expectancy-based thinking. Representativeness Tendency to make judgments according to After a coin has come up head many times heuristic how well the event matches our in a row, we may erroneously think that the expectations next flip is more likely to be tails. Availability heuristic Idea that things that come to mind easily We may overestimate the crime statistics are seen as more common in our own area, because these crimes are so easy to recall. Eyewitnesses to crimes are also frequently overconfident in their memories, and there is only a small correlation between how accurate and how confident an eyewitness is. When we experience a situation with a great deal of emotion, we may form a flashbulb memory, which is a vivid and emotional memory of an unusual event that people believe they remember very well (Brown & Kulik, 1977). People are very certain of their memories of these important events, and are typically overconfident. Talarico and Rubin (2003) tested the accuracy of flashbulb memories by asking students to write down their memory of how they had heard the news about 160 either the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks or about an everyday event that had occurred to them during the same time frame. Then the participants were asked again, either 1, 6, or 32 weeks later, to recall their memories. The participants became less accurate in their recollections of both the emotional event and the everyday events over time, but the participants? confidence in the accuracy of their memory of learning about the attacks did not decline over time. After 32 weeks the participants were overconfident; they were much more certain about the accuracy of their flashbulb memories than they should have been. Schmolck, Buffalo, and Squire (2000) found similar distortions in memories of news about the verdict in the O. Source monitoring refers to the ability to accurately identify the source of a memory. Perhaps you have had the experience of wondering whether you really experienced an event or only dreamed or imagined it. Rassin, Merkelbach, and Spaan (2001) reported that up to 25% of college students reported being confused about real versus dreamed events. Studies suggest that people who are fantasy-prone are more likely to experience source monitoring errors (Winograd, Peluso, & Glover, 1998), and such errors also occur more often for both children and the elderly, than for adolescents and younger adults (Jacoby & Rhodes, 2006). In other cases we may be sure that we remembered the information from real life, but be uncertain about exactly where we heard it. Probably you would have discounted the information because you know that its source is unreliable. What if later you were to remember the story, but forget the source of the information? If this happens, you might become convinced that the news story is true because you forgot to discount the source. The sleeper effect refers to attitude change that occurs over time when we forget the source of information (Pratkanis, Greenwald, Leippe, & Baumgardner, 1988). Misinformation Effects A particular problem for eyewitnesses, such as Jennifer Thompson, is that our memories are often influenced by the things that occur to us after we have learned the information (Erdmann, Volbert, & Bohm, 2004; Loftus, 1979; Zaragoza, Belli, & Payment, 2007). This new information can distort our original memories such that we are no longer sure what is the real information and what was provided later. In an experiment by Loftus and Palmer (1974), participants viewed a film of a traffic accident and then, according to random assignment to experimental conditions, answered one of three questions: 161 Figure 5. In addition to distorting our memories for events that have actually occurred, misinformation may lead us to falsely remember information that never occurred. Loftus and her colleagues asked parents to provide them with descriptions of events that did, such as moving to a new house, and did not, suc as being lost in a shopping mall, happen to their children. Then without telling the children which events were real or made-up, the researchers asked the children to imagine both types of events. The children were instructed to think real hard about whether the events had occurred (Ceci, Huffman, Smith, & Loftus, 1994). More than half of the children generated stories regarding at least one of the made-up events, and they remained insistent that the events did in fact occur, even when told by the researcher that they could not possibly have occurred (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). Even college students are susceptible to manipulations that make events that did not actually occur seem as if they did (Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001). Some therapists argue that patients may repress memories of traumatic events they experienced as children, such as childhood sexual abuse, and then recover the events years later as the therapist leads them to recall the information by using techniques, such as dream interpretation and hypnosis (Brown, Scheflin, & Hammond, 1998). Other researchers argue that painful memories, such as sexual abuse, are usually very well remembered, that few memories are actually repressed, and that even if they are it is virtually impossible for patients to accurately retrieve them years later (McNally, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2003; Pope, Poliakoff, Parker, Boynes, & Hudson, 2007). Because hundreds of people have been accused, and even imprisoned, on the basis of claims about recovered memory of child sexual abuse, the accuracy of these memories has important societal 162 implications. Many psychologists now believe that most of these claims of recovered memories are due to implanted, rather than real, memories (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). Distortions Based on Expectations We have seen that schemas help us remember information by organizing material into coherent representations. However, although schemas can improve our memories, they may also lead to cognitive biases. Using schemas may lead us to falsely remember things that never happened to us and to distort or misremember things that did. For one, schemas lead to the confirmation bias, which is the tendency to verify and confirm our existing memories rather than to challenge and disconfirm them. The confirmation bias leads us to remember information that fits our schemas better than we remember information that disconfirms them (Stangor & McMillan, 1992), a process that makes our stereotypes very difficult to change. If we think that a person is an extrovert, we might ask her about ways that she likes to have fun, thereby making it more likely that we will confirm our beliefs. In short, once we begin to believe in something, such as a stereotype about a group of people, it becomes very difficult to later convince us that these beliefs are not true; the beliefs become self-confirming. Darley and Gross (1983) demonstrated how schemas about social class could influence memory. In their research they gave participants a picture and some information about a fourth-grade girl named Hannah. As the test went on, Hannah got some of the questions right and some of them wrong, but the number of correct and incorrect answers was the same in both conditions. Then the participants were asked to remember how many questions Hannah got right and wrong. Schemas can not only distort our memory, but our reliance on schemas can also make it more difficult for us to think outside the box. The first guess that students made was usually consecutive ascending even numbers, and they then asked questions designed to confirm their hypothesis: (?Does 102-104-106 fit? Upon receiving information that those guesses did fit the rule, the students stated that the rule was consecutive ascending even numbers. They never bothered to ask whether 1-2-3 or 3-11-200 would fit, and if they had they would have learned that the rule was not consecutive ascending even numbers, but simply any three ascending numbers. Duncker (1945) gave participants a candle, a box of thumbtacks, and a book of matches, and asked them to attach the candle to the wall so that it did not drip onto the table below (see Figure 5. The problem again is that our existing memories are powerful, and they bias the way we think about new information. In the candle-tack-box problem, functional Salience and Cognitive Accessibility fixedness may lead us to see the box only as a box and not as a potential candleholder Still another potential for bias in memory occurs because we are more likely to attend to , and thus make use of and remember, some information more than other information. For one, we tend to attend to and remember things that are highly salient, meaning that they attract our attention. Things that are unique, colorful, bright, moving, and unexpected are more salient (McArthur & Post, 1977; Taylor & Fiske, 1978). In one relevant study, Loftus, Loftus, and Messo (1987) showed people images of a customer walking up to a bank teller and pulling out either a pistol or a checkbook. The salience of the stimuli in our social worlds has a big influence on our judgment, and in some cases, may lead us to behave in ways that we might better not have.

Order feldene 20 mg otc. Truth about Rheumatoid Arthritis Diet Treatment with Dr McDougall.

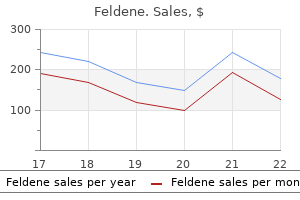

The second aim of the study was to analyze the association between a delayed high school start time later than 8:30 a arthritis stiff fingers buy feldene 20 mg with amex. Setting: Public high schools from eight school districts (n = 29 high schools) located throughout seven different states arthritis in dogs prevention buy cheap feldene 20 mg. A pre-post design was used for a within subject design arthritis diet livestrong 20mg feldene, controlling for any school-to-school difference in the calculation of the response variable arthritis pain relief gloves reviews buy feldene 20 mg on line. This is the recommended technique for a study that may include data with potential measurement error arthritis toes buy feldene 20mg with visa. Conclusions: Attendance rates and graduation rates significantly improved in schools with delayed start times of 8:30 a arthritis relief otc discount feldene 20mg amex. School officials need to take special notice that this investigation also raises questions about whether later start times are a mechanism for closing the achievement gap due to improved graduation rates. Keywords: Delayed school start times; high school bell times; attendance rates; graduation rates; graduation completion; inadequate sleep; insufficient sleep; adolescent sleep; student social-emotional health 113 3 Introduction Sleep experts agree that school start times are not in synchronization with 1, 2, adolescent sleep cycles, affecting learning and overall wellbeing of students. Proven 3, 4,5 scientifically, the drive to fall asleep and alert from sleep shifts during adolescence. Previous studies suggest that adolescents need nine hours or more a night to function at 4, 6, 7 peak performance making 8:30 a. Two national convenience samples were studied to compare changes in bedtime and wake-time from 1981 and 2003-2006 among adolescent students aged 15-17 years old. Findings from this comparative study indicated that over the span of time socio-economic factors and daytime activities predicted weekday bedtime, and school 13 start time predicted weekday wake time. If irregular pubertal sleep patterns result in a decreased sleep drive before 11:00 p. Using basic math calculations, it is evident that the amount of sleep recommended is difficult if not impossible to obtain based on the majority of existing bell schedules. To date, a concern lingers that a failure to shift start times may lead to chronic sleep deprivation in high school students. A disconnect occurs because the only way to overcome sleep deprivation is to increase nightly sleep time to satisfy biological sleep needs, a solution that is not an option for most adolescents given 15 the existing bell times. The report indicated that fewer than 20% of middle and high schools start at 8:30 a. More specifically, 42 states reported that 75%-100% of public schools start 16 before 8:30 a. Survey findings raise awareness about the reluctance by school 17 officials to adjust bell schedules to match adolescent sleep patterns. Further, decisions to condone existing start times persist despite politician and physician attempts to urge 18, local district and state leaders to consider scientific evidence before setting bell times 19, 20 5. Stated clearly in a 2005 study published in Pediatrics, physicians concluded boldly that decision-makers set students up for failure by endorsing traditional school schedules. The plea to delay start times are not only expressed by physicians but also by politicians that have called for federal oversight to enact public policies that align to the 19 sleep/wake cycle. Reasons to dismiss schedule changes vary however one argument against the implementation for later school start times is due to a belief by stakeholders that delayed adolescent sleep onset is a behavioral choice, influenced by factors such as 21 socializing with peers and accommodating late job schedules. This stance seems counterintuitive given that evidence suggests that biological processes of the sleep/wake 4, 5 cycle, and not merely teen preferences, are responsible for the delay in drive for sleep. Consequences of inadequate sleep An important research finding to consider is that insufficient sleep has been associated with an increase in suicidal attempts, suicidal ideation, substance abuse and 114 4 22 depression in adolescents. Winsler and colleagues surveyed adolescents (n=27,939) and conclude that a shortened duration of sleep by one hour increased feelings of hopelessness, doom, suicidal ideations, attempted suicides and substance abuse. Further, insomnia and major depression were two symptoms related to sleep quality and quantity 23 in a 2013 study. The study revealed teens that attempted suicide were found to have 24 higher rates of insomnia and sleep disturbance. Experts stress that the relationship between sleep disturbance and completed suicide is important to recognize and further suggest that this could be used as an indicator to initiate intervention and prevention 24 efforts in teens at risk for suicide. Other high-risk behaviors associated with inadequate sleep have been 25 investigated. Specifically, a study in Virginia found that students that started school at 8:30 a. Students that attended early classes were more likely to participate in criminal activity and had a higher incidence of engagement in risk-taking 27 behaviors such as drug or alcohol abuse. Further, inadequate sleep in teens has been linked to more problems with regulation of emotions and higher rates of mood disorders 28, 29 29. O?Brien and Mindell conclude from self-reports (Sleep Habits Survey and Youth Behavior Survey) distributed to 388 adolescent participants (14-19 years) that students that slept fewer hours reported greater alcohol use than students that slept longer on school nights. Teens that do not obtain an adequate amount of sleep are also more likely 27, 30 to smoke cigarettes, engage in sexual activity, and use marijuana. Benefits of sufficient sleep Evidence suggests that a delay in school start time promotes improvement in 12, 31 12 attendance and tardiness during first period classes. In this study th th there was a significant improvement in attendance rates for 9 -11 grade students not continuously enrolled in the same high school, with speculation offered that continuously enrolled students already had high attendance rates pre-delay start time so changes were 12 not as remarkable. Researchers note in the 1998 School Start Time Study that students attending schools with later start times were significantly less likely to arrive to class late 32 because of oversleeping, compared to peers attending schools with earlier start times. Research that compared the academic outcomes of two different middle schools in New England showed that students at the earlier starting school were tardy four times more 33 34 frequently. Recently, in a three-year study with 9,000 students in eight public high schools over three 35 states, Wahlstrom and colleagues found significant increases in attendance and reduced tardiness with a start time of 8:35 a. Importance of stakeholder consideration to adjust bell times the decision to continue to set high school start times earlier than 8:30 a. With all of the current emphasis on improving K-12 education, the potential of this study to demonstrate significant changes in attendance and graduation 115 5 rates of students simply by adjusting school start times is a critical component of educational reform and of critical importance to educational leaders. Scientific research has established the link between adolescent circadian-rhythms, sleep debt and negative impacts on cognitive function, behavior, attendance, health difficulties, and social and emotional health. Extended research that examines the impact of delayed start times in other districts throughout the country will add rigor to the previous findings. The second purpose of this study is to assess whether attendance rates improve with a delay in school start time of later than 8:30 a. Participants and methods this study examines the impact of delayed school start times on the percentage of high school absences and graduation rates at the school level. Additional data, graduation rates, and attendance rates, are obtained from state repositories. The current research was conducted utilizing the data from the state repositories of 29 schools in seven states and eight school districts (of 38 districts in the original study) specifically collecting attendance and graduation rates at two time periods (pre and post delay). This design controls for school-to-school differences, and eliminates competing explanations for any observed changes in the response variables. It is acknowledged that not all schools calculate the response variables using the same methodology. However, as mentioned, the design of the study, a within subject design allows for any school-to-school difference in the calculation of the response variable to be controlled for. This is the recommended technique for a study that may include 37 data with potential measurement error. For this study, results are intended to be generalized to all high schools in the United States. Hence, schools and school districts are not a random sample of all high schools and this may limit the generalizability of the results. To ensure a comprehensive treatment effect, only districts with post-start delay of over 2 years are included. The pre-post design ensures 116 6 that each school serves as its own control, minimizing effects due to school-to-school variability. The participating districts and the complete list of participating schools within each district along with the date of the time changes and increase in number of minutes from pre to post delay are included in Table 1. There is some variability in original start times (with a mean increase in minutes from pre to post time change of 74 minutes), but all meet the category of pre start times of 8:30 a. School start times are coded as a bivariate categorical variable coded as a zero (early start times) and one (later start times). School graduation completion percentages are measured by graduation rates collected from school districts ranging from zero to 100. Attendance averages 90% pre-delay and 94% post-delay, but is less variable than graduation rates with a range of 68% to 99% pre-delay and 86% to 99% post-delay. Descriptive statistics summarized each variable to identify any potentially erroneous entries or any non-normality in the continuous variables. Statistically significant relationships were determined based on an alpha level of. To remediate this, each response variable was reverse coded (subtracted by 1), and the log of this variable was calculated. Research Question 1 What are pre to post start time delay differences in graduation rates in the same schools one year before implementation of delayed start versus two years after the implementation of delayed start times? The standard deviation of 11% indicates differences greater than 36% were considered extreme. The next step in the descriptive statistics is a bivariate presentation of graduation rates by time. Table 2 includes the means, median and standard deviations for pre-delay and post-delay graduation rates. The mean at the pre-delay, earlier start times, is 79%, and the mean at the post-delay is 88%. The upward trend in the rates suggests graduation rates may be improving with changes in school start times. For both time periods, the median is slightly higher than the mean, indicating both time periods may also be left skewed, similar to the aggregate data. The boxplot in Figure 1 provides a graphical illustration of the graduation rates at both bell times. In this figure, the median for post-delay time appears higher than for the pre-delay. The null hypothesis for the model is that no difference exists in graduation rates between pre and post delay years (? The alternative hypothesis is that there is a significant difference between pre and post delay years (Ho:? Given that the assumptions are met, the model for determining if significant differences exist between pre and post delay graduation rates can be interpreted. Hence significant increases occurred in graduation rates comparing pre and post delay times. In Figure 1, the boxplot illustrates this trend, with the median for the post-graduation rates appearing to be greater than the median for pre graduation. Test of Fixed Effects Dependent Variable: Graduation Rates Source Numerator df Denominator df F Sig. These results are made with confidence because the model using transformed data meets the assumptions of normal distribution and equal variance. Question Two What are pre to post start time delay differences in the same schools one year before implementation of delayed start versus two years after the implementation of delayed start times in attendance rates? Descriptive Statistics Table 2 includes the means, median and standard deviations for pre-delay and post-delay attendance rates. The mean at the pre-delay, earlier start times, is 90%, and the mean at the post-delay is 94%. The upward trend in the rates suggests attendance rates may be improving with changes in school start times. The boxplot in figure 2 compares attendance rate pre-delay (0) and post-delay (1) time change and shows an average increase in attendance rates from 90% to 94%. There is at least one school in the pre-delay time that appears to have extremely low attendance, and one school that has extremely low attendance in the post-delay time as evidenced by the asterisks in figure 2. The equation for the model is: Attendance rate = year + error Again, the null hypothesis is that there are no differences between pre and post year (Ho=? This means that delayed start time is an important and significant predictor for improved attendance rates. The transformed data meets the assumptions of normal distribution and equal variance. Independence is still violated by the design of the model however running repeated measures remediates this assumption. The first research question investigated the potential benefits of delayed school start times of later than 8:30 a. Two of the school districts were located in the state of Florida, totaling 18 schools. The remaining 11 schools were found in school districts located in the states of Virginia, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Arkansas, and Minnesota. Research Question One: What are pre to post start time delay differences in graduation rates in the same schools one year before implementation of delayed start versus two years after the implementation of delayed start times? Research Question Two: What are pre to post start time delay differences in the same schools one year before implementation of delayed start versus two years after the implementation of delayed start times in attendance rates as a measure of social emotional well-being? The findings supported the hypothesis of the current study that students that started school later than 8:30 a. Discussion the results of this study lend empirical evidence and add rigor to the argument that a shift to later school start times for high school students results in more favorable outcomes, such as attendance rates and graduation rates. This study draws from the work 11 by Wahlstrom, who found improvement in attendance and graduation rates (one district) limited to only one state. While this study does not specifically measure the amount of sleep, the results are 11, 35 consistent with prior research linking later school start times to more sleep. The connection between later school start times and more sleep is important, but the results of significant improvements in graduation rates allow practitioners to see the positive, and socially important outcome of such a policy shift, increased graduation.

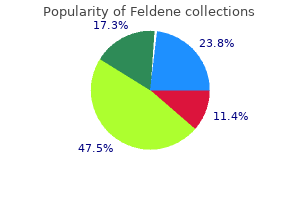

Delaying school starting time by one hour: Some effects on attention levels in adolescents arthritis upper back pain exercises cheap 20mg feldene free shipping. School start time and its impact on learning and behavior arthritis home medication order feldene 20mg otc, published in arthritis in the knees treatment for pain buy feldene us, Sleep and Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents arthritis in the knee cap buy feldene amex, ed arthritis in feet medication purchase feldene once a day. High school students with a delayed school start time sleep longer arthritis relief gloves reviews order feldene 20 mg without prescription, report less daytime sleepiness. Sleep tendency during extended wakefulness: Insights into adolescent sleep regulation and behavior. Sleepless in Fairfax: the difference one more hour of sleep can make for teen hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and substance use. Obese youths are not more likely to become depressed, but depressed youths are more likely to become obese. Dissimilar teen crash rates in two neighboring southeastern Virginia cities with different high school start times. The consequences of insufficient sleep for adolescents: Links between sleep and emotional regulation. Examining the impact of later school start times on the health and academic performance of high school students: A multi-site study. School start time change: An in-depth examination of school districts in the United States. Evidence is growing that having adolescents start school later in 4 the morning improves grades and emotional well-being, 2 and even reduces car accidents. Opponents cite costly 0 adjustments to bussing schedules and decreased time after? Reduced time for extracurricular activities may Delaying start times can be a very cost-effective require scheduling adjustments or additional measure for raising student achievement. Empirical studies fnd sizable gains in test scores and grades from later start times for adolescents. A one-hour delay has the same effect as being in a class with a third fewer students or with a teacher whose performance is one standard deviation higher. Later start times are also shown to improve non-academic outcomes, such as mood and attendance, and reduce the frequency of automobile accidents. While changing start times is not costless, the benefts are likely to outweigh the costs. In the early 1990s, researchers discovered that adolescents experience major changes in their circadian rhythm, with an approximately three-hour shift toward later bed and wake-up times, making 7. However, because of this delay in circadian rhythm, adolescents are unable to fall asleep early enough to get eight or nine hours of sleep before they need to wake up for school, leading to an increase in daytime sleepiness. Thus, traditional school schedules affect adolescent sleep patterns by forcing adolescents to wake up and learn at a time when their bodies want to be asleep. A systematic review of adolescent sleep patterns across the world shows a linear trend toward later school-night bedtimes from age 11 to age 18 [3]. The majority of the students examined were deemed to be sleep-deprived after age 13. They have hired better teachers, reduced class size, increased their use of technology, and changed class content and pedagogy, among other measures. Delaying school start times to better align with adolescents? sleep?wake cycles offers sizable benefts to students? academic and emotional outcomes at a relatively low cost. Studies from multiple disciplines and from many countries have indicated that early school start times lead to sleep deprivation among students and that hours of sleep are positively correlated with academic achievement [4]. While both correlational and anecdotal evidence point toward the benefts of later school start times, the causal relationship between start times and academic achievement has only recently been studied. Scores on intelligence tests are signifcantly lower in the early morning hours for adolescents, which suggest that adolescents? circadian rhythms affect their ability to learn and perform [5]. This hypothesis is supported by research that fnds that college students perform better in classes that meet later in the day [6]. Similarly, in Chicago public high schools, both attendance and achievement are signifcantly lower in frst-period classes than in other periods; this effect is particularly strong for mathematics classes [7]. While these studies begin to shed light on the relationship between time of day and learning, the estimated effects are likely biased due to students? ability to select their classes. Thus, these studies cannot tell us about the causal relationship between school start times and student academic achievement. There are just a handful of empirical studies that have specifcally assessed the academic effects of school start times. Most of these studies take advantage of natural experiments based on exogenous changes in school start times. The frst study examined course grades earned by students attending Minneapolis high schools in the three years before and the three years after the start time change and found a small, but statistically non signifcant, improvement [8]. Grading often has a subjective component, and therefore grades are not easily comparable across instructors or time, the study admits the challenge that arises in measuring academic success with this metric. Another study aimed to answer this question by looking at end of the year standardized mathematics and reading test scores in middle schools in Wake County, North Carolina. These differences enabled the study to explore the effect of later start times by comparing outcomes across schools with different start times and within schools that experienced a change in start time (some were assigned earlier start times while others were assigned later ones). The study fnds that an increase in start times by one hour leads to a three percentile point gain in both mathematics and reading test scores for the average student. Several characteristics of the academic setting there allow for a compelling study of the effects of start time. Second, students at the Air Force Academy are randomly assigned to their classes and professors during their frst year, which eliminates the issue of students selecting into certain classes or class times. Additionally, all students take standardized exams for their core classes, and grading is standardized across all instructors teaching the same course in a given semester. Figure 1, which presents the distribution of students? grades across the three different start times, shows that the later the start time, the higher the distribution of grades. The statistical analysis shows that a 50-minute delay in start times leads to a 0. Despite the fact that students at the Air Force Academy are not average adolescents (they were high achievers in high school and self-selected into a military academy), there is no reason to believe that this group of students would be more adversely affected by early start times than the average adolescent. The distribution of grades across school start times shows that the later the start time, the higher the distribution 0. The causal effect of school start time on the academic achievement of adolescents. Both the North Carolina and Air Force Academy studies fnd that the benefts of later start times are largest for students at the bottom of the grade distribution [1], [11]. Figure 2 shows how the effect of a one-hour delay in start times differs across the grade distribution at middle schools in Wake County, North Carolina. For instance, students in the 30th percentile of the ability distribution end up performing about three percentile points higher on the mathematics exam as a result of a one-hour delay in start time, while students at the 90th percentile perform around one percentile point higher. The fact that benefts differ across ability groups allows for opportunities to alter class schedules for some students if delaying the overall start time is not feasible. Students at the lower end of the performance distribution benefit more than others from a one-hour delay in school start times (a) Mathematics 3. The solid horizontal line is the average effect for all students, and the dotted horizontal lines bound a 95% confidence interval around the estimated average. For example, for schools that have free periods as part of the daily schedule, the lower ability students could be given the frst period off, allowing them to start their day later than their peers. Alternatively, their schedules could be set up so that they take their less rigorous classes early in the morning. The benefts of later school start times are quite large, especially when compared with other?more costly?educational interventions. As in previous studies, this gain can be quantifed as a dollar value in order to compare the benefts of this policy change with its potential costs [12]. A one standard deviation rise in test scores is estimated to increase future earnings by 8%. Assuming a 1% growth rate for real wages and productivity and a 4% discount rate, this translates to an approximately $10,000 increase in future earnings per student, on average, in present value terms. Channels of impact and optimal start times There are at least two channels linking later school start times to improved academic outcomes. Early start times lead to increased sleep deprivation, which affects students throughout the day. In addition, regardless of the duration of sleep, there are times of day when individuals are more alert and capable of learning. A second channel through which later start times can boost academic outcomes is through improved attendance in the frst classes of the day. At many schools, attendance is lower in early classes, and the later the start time, the higher the attendance in frst period classes [7]. While research has established that later start times can improve academic outcomes, no study has determined the optimal school start time. However, whether students would beneft more from having school start even later, 9. The Air Force Academy study assessed how student performance differs across class periods relative to frst period, holding all else constant [11]. As shown in Figure 3, the biggest gains would come from delaying start times to what is traditionally second or third period in many secondary schools (approximately 8. The costs of delaying school start times Delaying start times, while far more cost-effective than many other education policies aimed at improving student achievement, is not costless. Changes in grades across the school day suggest that later start times would boost achievement for secondary school students 0. For schools without bussing systems and those able to accommodate extracurricular activities in other ways, the cost of this policy change can be even smaller. To put the estimated costs discussed below in context, recall that delaying start times by one hour would result in an estimated 0. Many districts stagger the start times of their three levels of schools?elementary, middle, and high?to use one set of buses for all schools. Generally, the high schools start frst because of safety concerns arising from having younger children waiting outside for buses or walking to school very early in the morning, when it is still dark during much of the school year. Schools that currently provide bussing for their students and that want to change their high school start times will have to accommodate the change by having the other school levels start earlier (at no additional operating cost) or by operating more buses, at additional cost, so that all schools can start later in the morning. Another cost of later start times is the reduction in time available for after-school activities, such as athletic team practice. One option is to install lights on athletic felds so that students can practice later in the day. The estimated cost of adding lights to athletic felds would be a one-time expense of approximately $110,000 and an annual operating cost of $2,500 [12]. The second option is to alter students? schedules so that the last period of the day is made available for practice if they are on a sports team that practices outdoors. While this would not allow students to get more sleep, it would better align class times with the times of day that students learn best. LiMiTaTionS anD gapS One limitation of the literature on later school start times is that it has been unable to distinguish how much of the benefts of later school start times arise from absolute learning (how much someone has learned) and how much from relative learning (how much someone has learned compared to their peers). Because not all students at the Air Force Academy begin class at the same time, the study could not determine the effect of all students having an earlier or later start time. Similarly, the North Carolina study looked at percentile scores on standardized tests as an outcome, which, by construction, are relative to peers? test scores in the same year. In that setting, students? percentile scores may increase as a result of later start times not only because of more sleep and increased learning in the classroom, but also because the test is taken at a time when students perform better. Because adolescents have different internal clocks and sleep patterns than younger children and adults, early school start times are not conducive to their learning. Empirical studies of the impact of later start times on adolescents fnd sizable gains in grades and test scores. Scholars across disciplines agree that adolescents would beneft from later school start times. A growing body of research outside of economics has found that delaying school start times has positive effects on a number of non-academic outcomes as well, including hours of sleep, attendance rates, mental health, and frequency of automobile accidents [13]. This pattern was also detected empirically in the study of Wake County middle schools, which fnds that the benefts of later school start times increase with students? age [1]. Thus, the policy discussion about later start times should focus frst on high schools and then on middle schools, but does not apply to elementary schools. These fndings suggest that schools and districts have an opportunity to improve student learning and achievement by delaying middle and high school start times. Every school and district will face its own set of challenges associated with changing start times. Schools that do not provide bussing, have a dedicated set of buses for high school students, or already have lighted athletic felds will face the lowest associated costs. A pilot study can be a useful tool for schools and districts to assess the impact of the schedule change on their students. Districts with multiple high schools may choose to have one of the schools start later, while districts with one high school can institute a split schedule in which one set of students starts (and ends) the school day later. For schools that are unable to delay start times, changing the confguration of the school schedule may also improve student outcomes. Research suggests that the benefts from later start times come not only from allowing students to get more sleep, but also from having classes that are better aligned with the time of day when students are best able to learn. Better alignment can also be achieved by scheduling extra-curricular activities, electives, and non-academic classes (such as physical education) at the start of the school day. One of the biggest challenges to changing start times is measuring the impact of the change. Course grades at most schools are subjective, curved (assigned to yield a pre-determined distribution of grades), and not comparable across years or instructors.