Richard Gumina, MD

- Director of Interventional Cardiovascular Research and

- Co-Director of the Ischemia and Metabolism

- Thematic Research Davis Heart and Lung Institute, Assistant

- Professor of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University

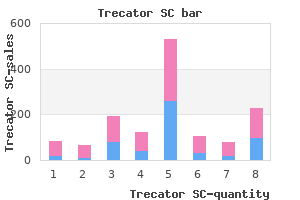

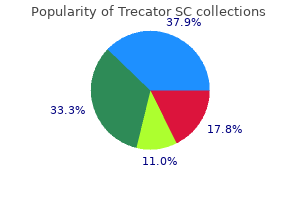

It begins almost immediately after the insult and may last for up to 3 weeks [38] medicine 666 purchase trecator sc 250mg with visa. Injuries at or above T6 are particularly associated with hypotension symptoms for pregnancy generic trecator sc 250 mg on line, as the sympathetic out flow to splanchnic vascular beds is lost symptoms dust mites discount trecator sc online amex. Other causes of hypotension should be excluded such as blood loss associated with other injuries treatment ind purchase genuine trecator sc online, since a hemorrhagic shock will not be accompanied by a compensa tory tachycardia symptoms gallbladder cheap trecator sc 250 mg otc. Preoperative Assessment Chapter 14 385 Ventilatory impairment increases with higher levels of spinal injury medicine that makes you throw up discount trecator sc 250 mg free shipping. Injuries higher than T7 have an 85% chance of producing serious cardio following the spinal cord vascular derangement [40]. If left untreated, the syndrome can provoke a hypertensive crisis causing seizures, myocardial ischemia or cere bral hemorrhage. Because of the increased prevalence of coronary heart disease, cardiac as Organ-specific assessment. Specialattentionshouldbepaidtopatientsbear 386 Section Peri and Postoperative Management ing an increased risk where coronary heart disease during spinal shock, a traumatic sympathectomy has not been proven. Most pediatric cardiac com below the lesion which begins almost immediately promise is a result of the underlying pathology. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway (2003) Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Gerlach R, Raabe A, Beck J, Woszczyk, Seifert V (2004) Postoperative nadroparin adminis tration for prophylaxis of thromboembolic events is not associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage after spinal surgery. Kawakami N, Mimatsu K, Deguchi M, Kato F, Maki S (1995) Scoliosis and congenital heart disease. Stiller K, Montarello J, Wallace M, Daff M, Grant R, Jenkins S, Hall B, Yates H (1994) Efficacy of breathing and coughing exercises in the prevention of pulmonary complications after coronary artery surgery. Multimodal Special airway management and positioning analgesia is the cornerstone. Careful surgical technique and positioning, antifibrinolytics, Historical Background Precise information is not available about the first anesthesia for spine surgery. In the 1970s the wake-up test was described to assess the integ rity of the spinal function. At the same time larger doses of opiates became popular to help maintain stable hemodynamic conditions and better pain control intra and postsurgery. Goals of Anesthesia in Spinal Surgery the role of anesthesia care in spinal surgery must be appreciated within the context Optimal teamwork between of comprehensive perioperative care where a dedicated team takes care of a patient the surgeon and anesthetist from preoperative planning and perioperative care to rehabilitation and discharge. Partic ular emphasis on trauma, scoliosis, and degenerative and cancer surgery is given. Although seemingly trivial, the consequences of these rules being ignored are often seen in daily clinical practice. A second cannula is inserted after the patient is asleep unless a central venous catheter is considered. The choice of induction agent (propofol, thiopental, opiates, etomidate or inhaled agents in children) will depend on the general condition of the patient and the presence of trauma associated hypovolemia, cardiac conditions and cord com Intraoperative Anesthesia Management Chapter 15 391 pression with marginal blood perfusion. The choice of muscle relaxants to facilitate the intubation will be influenced by conditions like full stomach, gastroesophageal reflux and trauma. Nondepolarizing agents such as rocuronium, vecuronium and cisatracurium have a safe record and are widely used today in spine surgery. In this setting, however, other factors such as hypotension and patient positioning may be even more important. Laryngoscopy with manual inline stabilization by the surgeon or with a stiff collar is an accepted means of intubation for many patients with an Direct laryngoscopy should unstable cervical spine as long as movement of the neck can be avoided [48]. Observe on the screen the deflated cuff of the endotra cheal tube under the epi glottis crossing the vocal cords. Thebuilt-inbronchialblockerisadvancedunderdirect fiberscopic vision through its channel to the main bronchus of the nonde pendent lung. Changing the tube with the patient in the prone or lateral position or during cervical spine surgery might be catastrophic. For anterior lumbar approaches, the stomach is decompressed of gas and secre Careful eye and face tions by using the gastric tube. Careful eye protection with cream, occlusive tape protection is crucial and peripheral padding is mandatory in particular in patients positioned prone or in anterior approaches to the cervical spine (Fig. In prepping the neck for posterior approaches, irritant solutions might reach the eyes from behind, remaining there for hours with the potential for severe corneal damage. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Postoperative infections in spine surgery are primarily monomicrobial, although Routine antibiotic in about half of infected patients more than one organism can be identified. The prophylaxis today is bacteria most commonly cultured from wounds are Staphylococcus aureus and standard in spinal surgery epidermidis [17]. Increased risk of spine postoperative infections has been associated with: staged procedures blood loss in excess of 1000 ml surgery longer than 4 h smoking diabetes malnutrition obesity immunocompromised patients alcoholism posterior approach postoperative incontinence 394 Section Peri and Postoperative Management cancer surgery extended preoperative hospitalization intraoperative hypothermia For the antibiotic prophylaxis to be effective, a drug with bactericidal activity against the most common infecting organisms must be present in the tissues at risk from the moment of the incision and for the duration of the surgery. The agent should be started within 30 min before and/or substantial skin incision. These prac tices will result in the most efficacious and judicious use of antibiotics [14]: maintaining therapeutic concentrations when appropriate avoiding excessive cost minimizing emergence of resistant microbial pathogens Although adverse reactions are actually rare, patients with a history of these events should receive an alternative antibiotic; vancomycin or clindamycin are second line choices in this setting. The use of antimicrobial prophy laxis in spinal surgery can reduce the number of both superficial and deep wound infections. The benefits of this intervention include less patient pain and discom fort, shorter hospital stays, and fewer expenses. In some procedures (such as ante a successful outcome roposterior lumbar surgery) the patient is repositioned while asleep to complete the operation. In elderly patients with severe cervical spondy losis, positioning with the neck in extension may result in spinal cord compres sion between the ligamentum flavum and posterior vertebral body osteophytes. The arms rest without axillary or elbow pressure and at a 90-degree angle in the shoulders and elbows. The abdomen must hang free [58] to decrease the abdomen must hang pressureontheinferiorvenacavaandsubsequentlyreduceepiduralveinpres free with the patient sure and bleeding (Fig. The prone position might represent an advantage from a respiratory point of view in patients properly positioned with a free-hanging abdomen due to functional improvement in residual capacity and oxygenation [59]. Jackson tables provide some advantages; however, precautions must be taken to minimize compression and traction of lines and anatomic struc tures. Cervical spine procedures call for a thorough final check of lines and tubes before prepping and draping. The endotracheal tube, nasogastric tube and tem perature probe have to be secured. Current evidence based preoperative recommendations do not endorse shaving the skin. Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Perioperative increased Increases in intraocular pressure with ischemic optic neuropathy have been intraocular pressure linked to blindness after the patient has been in the face-down position in spine may lead to ischemic surgery [72]. In patients free of ocular pathology under going spine surgery in the prone position, Cheng et al. Less common causes are central retinal artery or vein occlusion and occipital lobe infarct. We favor the use of the Mayfield head clamp for posterior cervical spine procedures because pressure on eyes, nose, and chin can be avoided. Established in July 1999, the registry col lects information anonymously (http:depts. Maintenance of Anesthesia Maintenance of anesthesia is intended to provide good surgical (a dry field, good neuromonitoring, adequate muscle relaxation when needed) and anesthetic con ditions (amnesia, nociceptive suppression, temperature preservation, hemody namic and organ function stability). It has been our experience that for thoracolumbar and lumbar spine surgery the use of intrathecal single shot morphine (0. Any choice of maintenance drugs must aim to give a stable depth or level of anesthesia. A theoretical advantage of having some degree of muscle relaxation in major posterior procedures is better abdominal decompression as opposed to the abdominal tightness of an unre laxed patient. Plethysmography of the toe Simultaneous monitoring of the Hbsat and plethysmography in the toe and finger to detect arterial compression in the anterior lumbar approach. This is a noninvasive device for following brain Hb-oxygen mixed satura tion in the territories supplied by the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Maintenance Fluids the type and volume of fluid maintenance will vary depending upon the magni tude of blood loss, the preoperative intravascular filling status, the systemic pre operative condition of the individual and the length of the procedure. Bladder catheters are routinely inserted before procedures lasting for more than 3 h to preclude bladder distension and to monitor urine output. Large blood volume changes and the frequent use of vasoactive drugs make their use manda tory to observe urine output in these situations. Foley catheters are also recom mended to be inserted in elderly male patients who suffer from prostate hyper plasia and patients with urinary incontinence. Routine use of air-warming blankets and intrave nous blood/liquid warming systems is recommended. Patients that are only partially paralyzed 400 Section Peri and Postoperative Management produce more heat compared with those fully paralyzed. Although malignant hyperthermia nowadays is a very rare condition, its incidence is increased in patients with scoliosis because of their association with neuromuscular pathology. Bear in mind that the other components of anesthesia (autonomic response, muscular relaxation, nociception, etc. It con sists of a barrage of four electrical impulses delivered transcutaneously over the ulnar nerve at 2 Hz to activate the adductor pollicis. Intraoperative Anesthesia Management Chapter 15 401 Nosocomial infection rates increase fivefold in patients receiving allogenic trans Transfusions increase fusions with a dose-response pattern; the more units received the higher the odds the risk of postoperative of infection [16]. Good spine surgeons complete the surgical procedures in less time, are careful with hemostasis, and pay attention to optimal patient positioning while looking for better outcomes. In posterior surgical approaches there is more bleeding because of the bigger incisions, more work on the laminae and facet joints, greater chances of epidural vein damage and bleeding and bone graft harvesting [15]. Neuromuscular scoliosis patients have greater blood loss during spinal fusion Neuromuscular scoliosis surgery than idiopathic scoliosis patients. Cell Salvage Intraoperative cell salvage consists of collecting the blood from the surgical field to a machine that separates red blood cells from detritus, washing and concen trating them to be reinfused into the patient. Cell salvage is contraindicated in: infected patients cancer surgery In a provocative approach, some authors have reinfused collected blood in a large number of cancer patients after irradiation of the bag to kill any malignant cells which are potentially present [25]. An increase in coagulability, changes in kaolin/Celite times or severe allergic reactions associated with the use of aprotinin have not been reported with tranexamic acid [26]. Desmopressin has not proven useful in decreasing blood losses [76] in idiopathic scoliosis surgery. A wide range of between 50 and 200 g/kg has been Intraoperative Anesthesia Management Chapter 15 405 advocated. Because of its clearance (35 ml/kg/h), it is suggested to repeat the dose every 2 h in case of persistent hemorrhage [82]. Coagulopa thy associated with massive transfusion is clinically characterized by the pres ence of microvascular bleeding or oozing from the mucosae, wound and punc ture sites. Intraoperative Spinal Cord Monitoring Patients undergoing corrective surgery for deformity are at a higher risk of spinal cord injury. Neurological deterioration can occur because of ischemia of the neural structures secondary to mechanical com pression and/or vascular stretching. Monitoring must be performed by an expe Spinal cord monitoring rienced team and the surgeon must be interested in acting on the findings [18]. Important facts regarding anesthesia stability and depth, hemody namics, blood volume, blood flow autoregulation of the spinal cord and tempera ture must be considered.

The authors concluded that it was not possible at that time to connect lesions with specific blade types due to the 216 variables involved and the lack of knowledge regarding their individual degrees of influence medicine while breastfeeding buy 250 mg trecator sc overnight delivery. The vast majority of the sharp force lesions identified in the Sidon Crusaders are suggestive of heavy-bladed weapons such as swords or possibly axes of some sort medications reactions order trecator sc 250 mg with visa. The articulated left hip and left femur from burial 101 (context 4169 LegG) exhibited a very thin medicine 93 2264 purchase trecator sc master card, well defined linear fracture of the posterior aspect of the femoral head (see Figure 96) medications removed by dialysis buy discount trecator sc 250 mg on line. There was some slight evidence of associated fracturing of the corresponding superior lateral aspect of the acetabular rim symptoms 0f parkinsons disease buy trecator sc 250mg without a prescription, although this was minimal symptoms exhaustion trecator sc 250 mg line. It is possible therefore that the wound of this left femur was inflicted with a wider blade than is suggested. However, the injury was estimated to have penetrated the bone to a maximum depth of nine millimetres, yet no evidence of plastic deformation or significant end fractures was observed to the femoral head itself, characteristics that might be expected in such a deeply penetrating wound produced with a broad, heavy blade. The possibility certainly remains that this wound was inflicted with a smaller, thinner blade more characteristic of a dagger or knife. Alternatively, the cut might potentially relate to some sort of early post-mortem treatment or processing (yet still within the peri-mortem timeframe of bone mechanical properties); the suggestion being that this cut is very similarly positioned to those observed in dismemberment practices. A third possibility is that this injury represents a form of denigration targeting the groin region, possibly castration, likely occurring once the victim had been incapacitated. Several of the injuries observed in the Sidon material demonstrate evidence for weapons with extremely sharp blade edges. Most notably one right mandible exhibits complete transection and loss of almost the complete inferior half of the right mandibular body (Figure 97A). Other useful characteristics included the presence of smooth fracture surfaces, bevelling or oblique/acute angled fracture surfaces relative to endocranial cortical bone surfaces. Staining of fracture surfaces was generally taken to be a prerequisite for the consideration of peri-mortem timing. This, of course, does not preclude the possibility that breakage occurred post-mortem in antiquity, with fracture surfaces subsequently becoming similarly stained to resemble genuine peri-mortem fractures. Hence, it was felt staining alone could not be used to definitively assess timing of trauma, although it was used to flag possible or probable peri-mortem lesions. This was particularly pertinent to the remains excavated from the lower part (layer 4 down) of the west end of burial 110. The top layers of these remains were first exposed during the 2009 excavation season, but due to time constraints and following clarification that the deposit continued into the unexcavated baulk at the time, it was necessary to recover and backfill the grave until the following season. It is possible that water percolating through the protective covering may have deposited fine sediment on top of the bones, potentially producing staining of any recent dry fracture surfaces which might have occurred either during the first season of excavation or during the interval between excavation seasons. Many of the bone elements or fragments observed to exhibit possible peri-mortem blunt force trauma exhibited differential staining across the fracture surface(s). Although parts of some fracture surfaces were clearly recent, likely occurring during excavation or as the bone dried out, other sections of the same surface could be stained and thus represent at least old dry fractures, if not peri-mortem breaks. It was felt such instances of variable staining across a fracture surface may represent bone fractures that were originally incomplete, i. It is difficult to be certain whether the majority of the blunt force trauma observed in the Sidon Crusaders can be attributed to interpersonal/inter-group violence, or if the peri mortem mechanical properties of the bones persisted long enough for these changes to have occurred as a result of taphonomic processes active before, during and after the final deposition of the remains within the fortification ditch. However, the presence and broad distribution of the sharp force trauma observed, along with the circumstantial evidence deriving from both the archaeological context and the historical accounts, would suggest a significant number of the blunt force lesions resulted from the same events that produced the sharp force lesions. Crusader period sites which have yielded weapon evidence from archaeological deposits include Arsuf (Raphael and Tepper, 2005; Ashkenazi et al. Of the 1243 arrowheads recovered during archaeological excavations carried out at Arsuf, almost all are of a similar type with the average length 4. The cross section was either square or diamond-shaped, demonstrating they were primarily armour piercing in design (Raphael and Tepper, 2005: 85-86). Figure 98 shows the types of arrowhead reported at Arsuf: Figure 98: Typical iron arrowheads recorded at Arsuf/Arsur. Note all examples are tanged rather than socketed in contrast to the copper alloy arrowhead recovered from burial 110 at Sidon (Amended after Ashkenazi et al. Only five arrowheads differed from this design and these were all kite-shaped and flat, a design generally suggested to have been preferentially used in hunting wild game or, alternatively, for wounding horses and mounts in battle. It is possible that taphonomic conditions have not allowed for the good preservation of such small, iron objects. Even so, the preservation of iron artefacts within burial 110, in particular the iron nails and the very small iron tacks, argues against this explanation. Al-Sarraf (2002) provides measurements for the types of swords in use during the Mamluk period. The term qaljuri and its equivalents became common in the Arabic literature from the 11th century onwards, although the earliest references to such swords derive from Fa imid sources in Egypt. These swords were described by contemporary sources as having curved blades (Al-Sarraf, 2002: 171). Although this image is considerably later than the events of the Seventh Crusade, the presence of such curved swords fits well with the pattern and timing of their development. Sabres later became increasingly prevalent as cavalry weapons, even after the introduction of early fire-arms into the Early Modern period. One individual from the Golancz castle mass grave (attributed to the 1656 siege and subsequent massacre on the site) presents a sharp force injury of the left temporal bone, with the majority of the mastoid process transected and missing (Lukasik et al. This lends some support to the interpretation of mounted troops using curved, sabre-like swords. Counter to this, however, is another example of a very similar wound reported at the Viking period execution site at Ridgeway Hill (Skull 3728 in Loe et al. Two general categories of axe are broadly accepted as forming part of the Islamic military arsenal from the early medieval period onwards. The first of these constitutes a smaller type, usually considered to be a saddle-axe, consisting of a light, short hafted, small-bladed war-axe used by cavalry. The second category is characterised by much larger examples, with long-hafts, representing heavy-bladed war axes (Al-Sarraf, 2002: 162). However, Al-Sarraf (2002) argues that the dual nomenclature derives from different chronological periods rather than indicating the two separate types of war-axe. Never-the-less, there is evidence for both types of war-axe within the historical accounts. Al-Sarraf does, however, argue that by the Mamluk period, the war-axe or abar had 225 become a high-status weapon, with its use limited to high-ranking officers (Al Sarraf, 2002: 164). Figure 100 below shows the similarity between what is considered a northwest European bearded axe-head, broadly contemporary with the crusades, and a later period Mamluk war-axe. Figure 100: A) Head of a bearded battle-axe, perhaps northwest-European, 1100-1350 (19. Original image: Worcester Art Museum; B) Battle-axe with Mamluk blazon, inlaid with gold, Syrian, c. Certainly, both swords and axes, whether long-hafted or short-hafted, were clearly capable of inflicting the types of weapons. Some of the extreme injuries identified and those others of injuries evidenced in the human remains from the crusader mass grave deposits. However, the incomplete and highly fragmented nature of the skeletal material inhibits the identification of wounds specifically attributable to one or other group suggested, indicate either very heavy strikes or extremely sharp implements or more likely a combination of the two. Maces Concerning the use of blunt force weapons, the series of superficial lesions observed to the superior left side of the back of the head of context 4247 can potentially be interpreted as subtle evidence of a heavy, multi-pointed object impacting the cranium, perhaps at the anterior-most lesion where there are slight radiating fractures, and rolling in an arc posteriorly across the surface of the head (see Figure 68). Ingelmark (1939: 191), in his early treatment of the human skeletal remains from the Battle of Wisby, stated that mace injuries were extremely difficult to identify due to the nature of the trauma they produced. Distinguishing any blunt force trauma resulting from actual battle, not just mace injuries, from post depositional breakage occurring while bone retains collagen. In addition, and with specific reference to mace injuries, Ingelmark was possibly too pessimistic, as he seems to have neglected the possibility of identifying the potential lesions caused by either spiked or flanged maces. Spiked maces are certainly attested in the archaeological record for the crusader period. A relatively well-preserved example was excavated at the site of Vadum Iacob, dating to the late 12th century (see Figure 15E). Thus, although far from being a definite case given their ephemeral/ambiguous nature, the cranial lesions observed in context 4247 certainly give pause for thought that such injuries are potentially identifiable. Some of the cranial and postcranial peri-mortem trauma presents as partially shaped or angled depressions that are highly suggestive of low velocity direct trauma caused by shaped or angular heavy blunt objects. The association of the sharp force wounds within the group makes it clear that these peri-mortem lesions are most likely the result of the same violent encounter. In this context, these lesions may well have resulted from direct impacts from a variety of different blunt weapons such as war hammers, clubs, maces, the hilts of swords, the hafts of axes or spears. Alternatively, some of these injuries, particularly where indirect trauma is indicated, may have been the result of other impacts likely occurring during inter-group violence. In the midst of battle, it is not hard to imagine being knocked down either by an opponent on foot or any mounted rider. In the early Islamic period, he describes how such weapons were broadly categorised into two distinct classes, the high status amud (a solid steel or iron mace or short staff) and the relatively low-tech dabbus (a lighter, round or oval-headed mace, with a wooden shaft). According to Al-Sarraf (2002: 159), the historical literature indicates the second of these weapons was closely associated with the ghilman troops, the initial institution of slave warriors established under 227 al-Muta im, a tradition later carried on with the founding of the Mamluk military institution. The heads of these lighter maces varied and included round-, oval and cucumber-types (the last indicating a cylindrical form). This was a heavier mace than the dabbus, potentially with a head of elongated teeth mounted on either an iron or wooden shaft, with a specific grip of shagreen. The reduced cost and easier handling of this heavier form of dabbus appears to have rendered the amud obsolete by the end of the 10th century. By the First Crusade, the terms dabbus and latt were almost interchangeable, but the former predominates from the 12th century onwards, having become a generic term for studded maces. Certainly, it seems the dabbus or one of its various forms may well have inflicted some of the blunt trauma evidenced in the skeletal material from burials 101 and 110. The distinctive concentration of blade wounds of the cervical region suggests deliberate targeting of this region. These cuts present some variety, particularly in their transverse angulation across the neck, as well as their depth of penetration but also demonstrate a general patterning indicating targeting of the back of the neck, with a slight focus on the right side suggested. Yet, the presence of other peri-mortem trauma distributed across the body and more significantly the variety in the penetration, siding and angulation of the cervical cuts themselves argue for a less ritualised situation dictating their occurrence. Certainly, a 228 randomised pattern of trauma is considered incompatible with interpretations involving formal execution (Jordana et al. On the other hand, one would not anticipate the back of the neck to be an easy target when fighting on foot, whether face-to-face with an adversary or chasing down a retreating/routed opponent. We might anticipate defensive wounds to the hands and upper limbs and targeting of the head or anterior left side of the neck in the case of the former and injuries to the back, legs (tibiae and fibulae) and feet might be expected to be more prevalent in the latter situation. On the whole the prevalence of cuts across the posterior and posterior right aspects of the neck suggests one or more assailants striking from an elevated position such as would be the case if the actor(s) were mounted on horseback. There is clear evidence of peri-mortem defensive wounds, with at least one individual exhibiting a heavy sharp force cut to the back of the right hand, indicating this individual at least was free to attempt to protect/defend themselves (Larsen, 1997). Such practices have been reported amongst numerous cultures widely distributed both temporally and spatially (Lambert, 2002; Steadman, 2008).

Order trecator sc line. Flu Vaccine: Myths and Facts | UCLA Health.

The range of places and institutions where the child may be cared for such as home treatment refractory buy trecator sc with amex, hospital medications janumet generic trecator sc 250mg mastercard, daycare treatment 8mm kidney stone cheapest trecator sc, pre school treatment diffusion buy trecator sc 250 mg with visa, school medicine 3605 v purchase trecator sc 250mg with visa, foster treatment with cold medical term buy discount trecator sc on line, respite facilities will need to be explored and often included in the management process. Management may need to incorporate liaison and visits to relevant environments where the child is, or will be, fed. Although inclusions of caregivers and family members is also relevant when managing adult clients with dysphagia, the actual knowledge, skills and needs of the family and caregivers will vary signi cantly from the child to the adult client. In view of the differences in anatomy and physiology between the child and adult, and changes in the developmental status of the child, specialist knowl edge and skills are required of the health professionals involved in paediatric dysphagia management. This is not to say that health professionals cannot work in both adult and paediatric areas; however, it is important that it is never assumed that the knowledge and skills are the same for adult and paediatric dysphagia management. When children present with feeding dif culties they are often at risk of insuf cient intake due to the increased time to feed, possible refusal patterns and physical, oro motor or swallowing dif culties (Ganger and Craig, 1990; Kamal, 1990). They are also at risk for stunted skeletal growth, poor weight gain, anaemia, speci c mineral and nutrient de ciencies and dental problems (White et al. For example, a child who is breastfeeding and not putting on weight may need to be complemented with bottle feeds to facilitate weight gain. The child who is only just learning to bite and chew solids may need opportunities to practise chewing more challenging chopped food at the beginning of a meal or at snack times, whilst their nutrition may be primarily met through purees. The therapist must consider that a full oral feed should be achieved within 40 minutes to 45 minutes for a newborn and by 30 minutes for a child above 6 months of age. This allows not only for adequate nutrition for growth and health but also allows the child to have normal sleep, wake times and developmental experiences. Mealtimes need to be scheduled to t in and around family, environmental and social routines as much as possible. For some children fatigue factors also need to be considered, with these infants and children requiring shorter oral feeding times to ensure adequate nutrition and safe swallowing. Many children with dysphagia may require supplementation of their oral intake (Ganger and Craig, 1990, White et al, 1993. A dietitian and paediatrician should be consulted regarding the appropriate selection and method of nutritional supplementation. Through team discussions an appropriate balance of oral versus non-oral intake, amount of intake, timing and dietary supplementation can be achieved. This will then ensure optimum health and growth of the child, whilst facilitating oral intake and skills. Achieving this balance can be challenging and may need regular and ongoing modi cation for the developing and changing needs of the child. The aim is for the feeding environment to be a calm, rhythmical setting where the child is able to focus on feeding and swal lowing. Aspects such as lighting, sound, noise and visual objects and patterns need to be considered and possibly modi ed, removed or relocated in the environment. Pastel walls and softer lighting are often more helpful than environments that contain busy visual patterns or loud, incon sistent or distracting noises. The therapist needs to observe aspects of the environment such as lighting, visual elements, noise, and rhythm. The therapist should then determine whether these have a positive or negative impact on the child and make appropriate modi cations as necessary. Our sucking and chewing mechanisms occur rhythmically and often the suck/swallow/breathe and chewing cycles are close to one cycle per second. Classical music with a moder ate tempo that mirrors this rhythm of one beat per second can be helpful. Music can also have a calming and focusing effect on the child and parent (Morris and Klein, 2000). The positive and negative impacts of using music during feeding should, therefore, be evaluated. Positioning and seating must take into consideration (a) the gross motor devel opment of the child, and (b) the need to support stability. In addition, positioning should aim to inhibit abnormal tone and re ex movement so that normal movement patterns may be facilitated. Options and suitable arrangements may vary depending on the physical environ ment, caregiver skills and available support (Macie and Arvedson, 1993). Access to equipment in a variety of settings will also need to be addressed as these may vary enormously. Children may be waiting for seating equipment or chairs and therefore interim and affordable measures may need to be investigated and provided. Simple, cheap and accessible resources may include, swaddling cloth, cushions, foam wedges, beanbags, rolled up towels, footstools, sports headbands, and car seats. Supportive, correct positioning for feeding is essential to facilitate appropriate head and neck posture to achieve optimal oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing and minimize the risk of aspiration (Wolf and Glass, 1992). It is important then, that the posture or position chosen will reduce the likelihood of fatigue for both the child and caregiver. If a seating or positioning arrangement cannot be maintained easily it is either likely to be modi ed by the caregiver or will deteriorate with time. Movement and functional skills such as feeding, re quire that the child has a stable base (Morris, 1985). With increased stability there is a greater chance for mobility to develop (Alexander, 1987; Macie and Arvedson, 1993). Movement and instability in the feet, legs and pelvis in uences what occurs in the trunk. These then in uence head and neck stability and then jaw, lip, cheek and tongue control (Morris and Klein, 2000). Development of movement control in one area of the body then signi cantly in uences development of movement in other areas of the body (Wolf and Glass, 1992; Macie and Arvedson, 1993). If stability of the head and neck is facilitated and abnormal movements and re exes are inhibited then normal feeding/swallowing movements and oro-motor functions are able to be facilitated in the developing child (Wolf and Glass, 1992). Positioning strategies and pur poseful intervention that inhibit abnormal patterns allow the child more independent and volitional movement. It is crucial that inhibition of abnormal patterns occurs in the very early years to maximize long-term oral-motor and feeding outcomes. For example, if children are fed with the head in an extended posture, this will perpetu ate and encourage jaw extension, which can often exacerbate tongue thrusting and poor feeding. This may involve moving from the breast or bottle to spoon/ ngers/ cup and later knife and fork. By facilitating assisted self feeding the child gains greater control over the feeding process, which may increase cooperation and alleviate possible behavioural problems associated with feeding. For example seating modi cation, correct tray placement, and elbow support that facilitates hand-to-mouth function and mouth opening will ultimately promote independent feeding. Before proceeding further with positioning strategies it is important to empha size that positioning needs to be a multidisciplinary process. The physiotherapist and occupational therapist are clearly vital team members to be consulted. It is also important for the speech pathologist to be an integral part of the process to facili tate oromotor function and ef cient, safe swallowing. The individual child and their family also play a key role in individualizing treatment. Seating supports, such as harnesses or strapping need to be safe for the child and abide by local and national safety standards, and occupational health and safety standards. Does it place the caregiver or child at risk of injury, compensatory posture or negative outcomes The newborn may need to be exed into a curled position with hips bent and knees exed. Similarly, to achieve a good sitting position the hips need to exed and the pelvis titled slightly back. In some cases it is marginally reclined to achieve a stable, erect and midline trunk position. This will also assist later propping of the elbows on the table or tray and independent use of the arms. Positioning of the shoulder girdle may be assisted by swaddling in the newborn or later by hand pressure or cuf ng of the arms or wrists. This usually means the knees should be bent to inhibit extension in the hips and knees. The head should be supported and maintained in a slightly forward posture with chin tucked. This will assist swallowing ef ciency and airway protection as well as inhibiting abnormal extensor patterns, and will allow for more controlled and coordinated movements of the mouth for feeding. Care should be taken however, to ensure that the posture does not inhibit respiration and contribute to airway collapse. Positioning of the newborn Infants do not have stability and volitional control of their movement at birth. Their movements are largely whole body or whole mouth movements and heavily in uenced by early re ex patterns (Morris and Klein, 2000). Newborn positioning techniques may include swaddling, speci c positions and use of positioning aids. Swaddling the infant provides external stability, improved general body exion and, assists in calming the infant which may allow for better oromotor function. For ex ample, infants with micrognathia (a small mandible) or macroglossia (large tongue) often bene t from a side lying or prone position that facilitates a more forward tongue posture and improved respiratory status during feeding (see Figure 15. Children born with a cleft palate may be fed in a more upright position to minimize nasal regurgitation of milk into their nasal passage during feeding. Children with gastro esophageal re ux are more often fed and slept in a more upright position to minimize their re ux and facilitate gastric emptying. Positioning of the child in a seated position Once the child is being fed solids or at the developmental stage to facilitate or achieve sitting, new positioning techniques to support this position may be incorporated. A pelvic strap is often the rst point of stability to assist with exion at the hips. If the pelvis and hips are stabilized this acts as an axis point and stability for the rest of the body. Feet often need to rest on a footplate and additional foot cuffs may be needed to secure and maintain feet positioning.

The teacher asked a question and he or she quickly provides the answer medications causing pancreatitis purchase 250 mg trecator sc free shipping, but is then confused by the annoyance of the other children treatment diabetes order generic trecator sc line, especially if they did not do the act medicine 5e buy cheap trecator sc 250mg on line. This can cause confusion to parents and teachers medications you cannot crush discount trecator sc 250mg on-line, as the previously honest (perhaps to a fault) child recognizes that one can deceive people and avoid anticipated consequences treatment uti infection discount 250 mg trecator sc mastercard. However medications 8 rights generic 250 mg trecator sc with visa, the type of deception can be immature and the deceit easily identified by an adult. Second, he or she may consider that a lie can be a way of avoiding consequences, or a quick solution to a social problem. What the person might not acknowledge is that lying can also be a way of maintaining self-esteem should he or she have an arrogant self-image, whereby the making of mistakes is unthinkable. They have subsequently been astounded that the organizational culture, line managers and colleagues have been less than supportive; this can lead to disillusionment and depression. The adjacent boy started to tease him by poking his fingers in his back while the teacher was not looking. Other children would have explained that they were provoked, and would recognize that if the teacher knew the circum stances, the consequences would be less severe and more equitable. The teacher continued with her story and a few moments later another child returned to the classroom from the toilet. When presented with a problem, seeking guidance from someone who probably knows what to do is usually not a first or even a second thought. Managing conflict As children develop, they become more mature and skilled in the art of persuasion, compromise and management of conflict. They are increasingly able to understand the perspective of other people and how to influence their thoughts and emotions using constructive strategies. They may fail to understand that they would be more likely to achieve what they want by being nice to the other person. They may have a history of pursuing their decision until the other person capitulates, and not recognize the signals that it would be wise not to continue the argument. Above all, they need to learn not to let emotion, especially anger, inflame the situation. Role-play games can be used to illus trate inappropriate and appropriate conflict resolution strategies. The child may acquire ToM abilities using intelligence and experience rather than intuition, which can eventually lead to an alternative form of self-consciousness as the child reflects on his or her own mental state and the mental states of others. Frith and Happe (1999) have described this highly reflective and explicit self-consciousness as similar to that of philosophers. When a different way of thinking and perceiving the world is combined with advanced intellectual abilities we achieve new advances in philosophy. Children at around eight years can inhibit their comments or criticism on the basis of their prediction of the emotional reaction of the other person; that is, they keep their thoughts to themselves so as not to embarrass or annoy their friend. Anxiety Being unsure of what someone may be thinking or feeling can be a contributory factor to general feelings of uncertainty and anxiety. In his autobiography he wrote: Because of my lack of confidence, I am terribly afraid of upsetting others without realising it or meaning to , by saying or doing the wrong thing. I wish I could read minds, then I would know what they wished for and I could do the right thing. Their answers to questions that rely on ToM abilities can be less spontaneous and intuitive and more literal, idiosyncratic and irrelevant (Bauminger and Kasari 1999; Kaland et al. One of the consequences of using conscious mental calculation rather than intuition is the effect on the timing of responses. The time delay for intellectual processing leads to a lack of synchrony to which both parties try to adjust. The person may have reasonable ToM abilities but have difficulty determining which signals are relevant and which are redundant, especially when inundated with social cues. The time taken to process social information is similar to the time it takes for someone who is learning a second language to process the speech of someone fluent in that language. If the native speaker of the language talks too quickly, the other person can only understand a few fragments of what has been said. This can have an effect on the formal testing of ToM abilities and may explain some of the differences between formal knowledge in an artificial testing situation, and real life, which is more complex, with transitory social cues and greater stress. Using cognitive mechanisms to compensate for impaired ToM skills leads to mental exhaustion. Limited social success, low self-esteem and exhaustion can contribute to the development of a clinical depres sion. One of my clients has an excellent phrase to describe her exhaustion from socializ ing. Pre and post-treatment assessment using the standard measures of ToM abilities has confirmed that the programs improve the ability to pass ToM tasks. However, these studies have not found a generalization effect to tasks not included in the training program. We know that children as young as three to four years understand that thought bubbles represent what someone is thinking (Wellman, Hollander and Schult 1996). Recent studies examining whether thought bubbles can be used to acquire ToM abilities in children with autism found some success with this method (Kerr and Durkin 2004; Rajendran and Mitchelle 2000; Wellman et al. For example, the child may decide to use a red crayon to indicate that the words spoken by the other child were perceived as being said in an angry tone of voice.