Cindy L. O’Bryant, PharmD, BCOP

- Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

- Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, University of Colorado Cancer Center, Aurora, Colorado

http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/pharmacy/Departments/ClinicalPharmacy/DOCPFaculty/H-P/Pages/OBryantCindyPharmD.aspx

Otherwise gastritis symptoms forum 20mg protonix otc, the sleep-related symptom is stated and coded this modifier is used when the name of the condition describes the symptom here if it meets the following criteria: and gastritis bananas buy protonix 20mg otc, therefore gastritis diet 6 months generic protonix 40mg mastercard, no symptom modifier is necessary diet during gastritis order protonix 40 mg on-line. The symptom produces disruption of the sleep episode continuity gastritis definicion buy 20mg protonix visa, Axis A Sleepwalking chronic gastritis histology buy protonix in united states online, mild, chronic 307. The digit for the second symptom is added to the code, the predominant complaint is an inability to sustain sleep due to: making a five-digit code. Frequent awakenings, Axis A Delayed Sleep-Phase Syndrome, moderate, chronic with excessive sleepiness, and difficulty and/or in initiating sleep 780. The Mental, Neurologic, or Other Medical Disorders should also be coded on axis A along with an appropriate sleep code if the disorders pro 4 With difficulty in awakening duce a major sleep disorder. The predominant complaint is usually difficulty in maintaining can be stated on axis A if the sleep disorder is due to the medical condi desired wakefulness, tion. Procedure Features the alphanumeric procedure-feature codes are derived from a letter of the alphabet that corresponds to a group of common features. The particu lar features are listed on axis B in the order of importance in determining (1) the major diagnosis and (2) additional sleep diagnoses. Axis C should list diagnoses suspected to be associated with axis A diagnoses, such as Hypertension associated with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Axis B sleep codes consist of an alpha character indicating the subgroup of procedures and a numeral for the particular feature being coded. Included beside each feature code, in brackets, are the alpha characters that may be appro priate to use with that particular feature. The alpha characters X, Y, and Z are reserved for use by researchers who wish to code for procedure features that are not listed here and that require greater specificity. It is planned to develop a database specification and create computer software for this purpose. The primary purpose of this database is to establish a format for epidemiolog ic tracking of sleep disorders at sleep-disorders centers. This standardized data processing tool will facilitate data pooling in cooperative intercenter ventures. The resulting overall multicenter database will also serve as a valuable informa tion resource in several ways. It will provide data for updating the classification system and assessing the usefulness of the proposed classifications. It will also furnish additional detail on the statistical criteria used in classification. Specifically, factors such as duration, associated features, severity, and diagnostic criteria, will be available for careful examination and reevaluation. To facilitate record keeping on the sleep disorders that clinicians encounter, a database system has been devised. One is simple and allows for data entry of minimal identification, demographic, and diagnostic infor mation. The other is more complex and allows for storage and retrieval of detailed information concerning the outcome of sleep studies and other examinations. In addition to providing the specification of each data field, the database was developed with several specific design goals. This flexibility will allow for transporting the actu al data out of the database in several forms so that other computer software can use the information. Flexibility also allows upward compatibility as revisions and new versions become available. The system incorporates various approaches to data logging, including selection from menus, checklist entry, and code-book entry. It is also expected that the general availability of a custom-tailored database system will encourage good clinical record-keeping practices. It has been sug gested that a report generator be developed so that simple patient summaries can be produced. Finally, the system will undoubtedly have inadvertent value in training and mastery of this new data base for the classification of sleep disorders. The following is a suggested manner in which the codes could be entered into a computerized database (the example given corresponds to the clinical example given on page 322). In this section, we present a differential-diagnostic listing of the sleep disorders that cause the primary sleep symptoms, insomnia and excessive sleepiness. Because many sleep disorders pro duce both symptoms, names in the lists are duplicated. Some sleep disorders can be asymptomatic or can produce other symptoms, and they are listed, therefore, in the Other Sleep Disturbances group. This third list is included to assist the clin ician in diagnosing a complaint of an abnormal event occurring during sleep such as a movement disorder. The organization of the differential diagnoses follows the method presented in the 1979 Diagnostic Classification of Sleep and Arousal Disorders. The lists include the disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep and the disorders of excessive somnolence. The sleep-wake schedule disorders, now called the circa dian rhythm sleep disorders, are included within the differential-diagnostic listing for insomnia and excessive sleepiness where appropriate. Excessive Sleepiness A complaint of difficulty in maintaining desired wakefulness, or a com plaint of an excessive amount of sleep. Other Sleep Disturbance An abnormal physiologic occurrence during sleep or during arousal from sleep that does not usually cause a primary complaint of insomnia or excessive sleepiness. Sleep-Related Painful Erections Actigraph: A biomedical instrument used to measure body movement. Other Active Sleep: A term used in the phylogenetic and ontogenetic literature for the 6. Electrical Status Epilepticus of Sleep Alpha Activity: An alpha electroencephalographic wave or sequence of waves c. Other Alpha-Delta Sleep: Sleep in which alpha activity occurs during slow-wave sleep. Other Causes of Sleep Disturbance Because alpha-delta sleep is rarely seen without alpha occurring in other sleep a. Sleep-Related Sinus Arrest Alpha Intrusion (-Infiltration, Insertion, Interruption): A brief superimposi c. Sleep-Related Abnormal Swallowing Syndrome tion of electroencephalographic alpha activity on sleep activities during a stage of d. Terrifying Hypnagogic Hallucinations Alpha Rhythm: In human adults, an electroencephalographic rhythm with a fre g. Other quency of 8 to 13 Hz, which is most prominent over the parieto-occipital cortex when the eyes are closed. It is most con sistent and predominant during relaxed wakefulness, particularly with reduction of visual input. The frequency range also varies with age; it is slower in chil dren and older age groups relative to young and middle-aged adults. Alpha Sleep: Sleep in which alpha activity occurs during most, if not all, sleep stages. Apnea: Cessation of airflow at the nostrils and mouth lasting at least 10 seconds. Obstructive apnea is secondary to upper-airway obstruction; central apnea is associated with a cessa tion of all respiratory movements; mixed apnea has both central and obstructive components. Apnea-Hypopnea Index: the number of apneic episodes (obstructive, central, and mixed) plus hypopneas per hour of sleep, as determined by all-night polysomnography. Apnea Index: the number of apneic episodes (obstructive, central, and mixed) per hour of sleep, as determined by all-night polysomnography. Arousal may be accompanied by increased tonic electromyographic activity and heart rate, as well as by an increased number of Cheyne-Stokes Respiration: A breathing pattern characterized by regular body movements. Arousal Disorder: A parasomnia disorder presumed to be due to an abnormal Chronobiology: the science relating to temporal, primarily rhythmic, processes arousal mechanism. This definition of awakenings is valid only inso Circasemidian Rhythm: A biologic rhythm that has a period length of about half far as the polysomnogram is paralleled by a resumption of a reasonably alert state a day. Conditioned Insomnia: An insomnia that is produced by the development of Axial System: A means of stating different types of information in a systematic conditioned arousal during an earlier experience of sleeplessness. A conditioned insomnia is one component of psychophysiologic Classification of Sleep Disorders uses a three-axial system: axes A, B, and C. Axis A: the first level of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders axial Constant Routine: A chronobiologic test of the endogenous pacemaker that system on which the sleep-disorder diagnoses, modifiers, and associated code involves a 36-hour baseline-monitoring period, followed by a 40-hour waking numbers are stated. Delayed Sleep Phase: A condition that occurs when the clock hour at which sleep Bedtime: the clock time when one attempts to fall asleep, as differentiated from normally occurs is moved back in time within a given 24-hour sleep-wake cycle. This results in a temporarily displaced, that is delayed, occurrence of sleep with Beta Activity: A beta electroencephalographic wave or sequence of waves with a in the 24-hour cycle. The same term denotes a circadian rhythm sleep disturbance, frequency of greater than 13 Hz. Beta Rhythm: An electroencephalographic rhythm in the range of 13 to 35 Hz, Delta Activity: Electroencephalographic activity with a frequency of less than 4 when the predominant frequency, beta rhythm, is usually associated with alert Hz (usually 0. In the scoring of human sleep, the minimum character wakefulness or vigilance and is accompanied by a high tonic electromyogram. Delta Sleep Stage: this stage is indicative of the stage of sleep in which elec Brain Wave: Use of this term is discouraged. The suggested term is electroen troencephalographic delta waves are prevalent or predominant (sleep stages 3 and cephalographic wave. Epoch: A measure of duration of the sleep recording that typically is 20 or 30 sec Drowsiness: A state of quiet wakefulness that typically occurs before sleep onset. Excessive Sleepiness (Somnolence, Hypersomnia, Excessive Daytime Duration Criteria: Criteria established in the International Classification of Sleepiness): A subjective report of difficulty in maintaining the alert awake state, Sleep Disorders for determining the duration of a particular disorder as acute, sub usually accompanied by a rapid entrance into sleep when the person is sedentary. Excessive sleepiness may be due to an excessively deep or prolonged major sleep episode. It can be quantitatively measured by use of subjectively defined rating Dyssomnia: A primary disorder of initiating and maintaining sleep or of exces scales of sleepiness or physiologically measured by electrophysiologic tests such sive sleepiness. Arousal): Synonymous with premature as a shift worker, who has the major sleep episode during the daytime. The extrinsic sleep disorders are a subgroup of the by means of electrodes placed on the surface of the head. Sleep recording in humans uses Final Awakening: the amount of wakefulness that occurs after the final wake-up surface electrodes to record potential differences between brain regions and a neu time until the arise time (lights on). Either the C3 or C4 (central Final Wake-Up: the clock time at which an individual awakens for the last time region) placement, according to the International 10 to 20 System is referentially before the arise time. The subject usually will habituate to the laboratory by the time one of the three basic variables used to score sleep stages and waking. These positions reflect maximally the changes in resting Fragmentation (Pertaining to Sleep Architecture): the interruption of any activity of axial body muscles. Along with the electroencephalogram Free Running: A chronobiologic term that refers to the natural endogenous peri and the electromyogram, one of the three basic variables used to score sleep od of a rhythm when zeitgebers are removed. Sleep recording in humans uses surface electrodes placed near seen in the tendency to delay some circadian rhythms, such as the sleep-wake the eyes to record the movement (incidence, direction, and velocity) of the eye cycle, by approximately one hour every day; this delay occurs when a person has balls. Rapid eye movements in sleep form one part of the characteristics of the an impaired ability to entrain or is without time cues. Hertz (Hz): A unit of frequency; the use of this term is preferred over the use of End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide: the carbon dioxide value that is usually determined the synonym, cycles per second (cps). The value reflects the car bon-dioxide level in alveolar or pulmonary artery blood. Subjects are instructed to try to remain awake in Hypnagogic: Occurrence of an event during the transition from wakefulness to a darkened room while in a semireclined position. This test is most useful for assessing the effects of sleep disorders or of medication upon the ability to remain awake. Hypnagogic Major Sleep Episode: the longest sleep episode that occurs on a daily basis. This sleep episode typically is dictated by the circadian rhythm of sleep and wake fulness; also known as the conventional or habitual time for sleeping. Microsleeps are associated with excessive sleepiness and automatic Hypnopompic (Hypnopomic): Occurrence of an event during the transition from behavior. Minimal Criteria: Criteria of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders Hypopnea: An episode of shallow breathing (airflow reduced by at least 50%) derived from the diagnostic criteria that provide the minimum features necessary during sleep, lasting 10 seconds or longer, usually associated with a fall in blood for making a particular sleep-disorder diagnosis. Disorders that refers to modifying information of a diagnosis, such as associated symptom, severity, and duration of a sleep disorder. Movement Arousal: A body movement associated with an electroencephalo graphic pattern of arousal or a full awakening; a sleep-scoring variable. This term is employed ubiquitously to indicate any and all gradations and types of sleep loss. The term is often used, especially in the French lit preceding and subsequent epochs are in sleep.

Thus gastritis diet ýëåêòðîííîå buy protonix 20 mg on line, the strain of the mouse and the initiating carcinogen determine the ability of phenobarbital to either inhibit or promote hepatocellular carcinogenesis in 15-day-old mice (Weghorst et al gastritis back pain purchase generic protonix on line. At weaning (28 days of age) diet during gastritis order genuine protonix, some groups received drinking-water containing 500 mg/L pheno barbital gastritis diet nih cheap protonix 40mg fast delivery, while others received deionized water gastritis enteritis purchase cheap protonix online, for 24 weeks chronic gastritis nexium cheap generic protonix uk. The authors concluded that the sex of mice was important in determining their susceptibility to promotion by phenobarbital (Weghorst & Klaunig, 1989). Control groups received a single intraperitoneal injection of saline alone and normal diet or the diet containing phenobarbital. At each of these intervals, 36 rats were transferred to the control diet and another 36 were transferred to a diet containing 0. Four rats from each group were killed at 21-day intervals starting 91 days after the beginning of the experiment. Treatment with phenobarbital for only 5 days had no effect on the incidence of tumours but produced a 60% increase in the number of animals with larger tumours (8/106 versus 5/106). When administration of phenobarbital was increased to 20 days, it had a slightly greater effect (35/108 versus 22/106). When the treatment-free interval was increased to 30 days, a slight reduction was seen in the enhancing effect of phenobarbital (68/106 versus 73/109). A dose-dependent effect of phenobarbital was clearly seen on both the number and size of enzyme altered islands at concentrations > 10 mg/kg of diet. The increase in the total number of islands in these groups was significant (p < 0. The numbers of enzyme altered islands in the largest size class (about 1000 m) were significantly increased at 100 and 500 mg/kg of diet (p < 0. Thus, phenobarbital given simultaneously with a low concentration of initiating carcinogen enhanced carcinogenesis at all the concentrations tested (Kitagawa et al. No hepatocellular carcinomas were found in rats exposed to phenobarbital alone or in those that were untreated. This was associated with an increase in the acido philic and mixed-cell character of the lesions (Ito et al. The authors concluded that baso philic foci may be more important than hyperplastic nodules in carcinoma formation (Driver & McLean, 1986a). Beginning on day 10, some groups of animals received phenobarbital in the drinking-water at 40, 100 or 1000 g/mL for the remainder of the 20 month-experiment. The authors concluded that the stage of initiation and promotion at which phenobarbital acts in hepatocarcino genesis in rats is altered by both the age and sex of the animal (Xu et al. Control groups of 30 rats each received either phenobarbital alone or remained untreated. Hyperplastic nodules developed in 8/30 rats that received the nitrosamine plus phenobarbital (p < 0. Subsequent administration of phenobarbital significantly increased the average number of hyperplastic nodules (5. Two weeks after the last injection, some groups of rats received drinking-water containing 0. Groups of male Fischer 344 rats [initial number not specified], 4 weeks of age, were given a single intraperitoneal injection of 0. Two weeks later, the rats were given either tap-water or water containing 500 mg/L phenobarbital for 78 weeks. None of the rats exposed to the nitrosamine alone developed liver tumours; however, subsequent phenobarbital treatment resulted in a significant increase in the incidence (5/15, p < 0. Phenobarbital promoted the development of thyroid tumours but not of any other tumours initiated by N-nitrosomethyl(acetoxymethyl) amine (Diwan et al. Phenobarbital was discontinued after the progressor agent was given, and animals were killed 6 months after administration of the progressor. Hepatic hyperplastic nodules were found in 100% of animals exposed to the nitrosamine with or without phenobarbital. Animals treated with phenobarbital alone developed significantly more foci than the untreated group (1. Treatment with phenobarbital alone did not result in tumour formation, but enlarged hepatocytes with abundant cytoplasm were observed. None of the nine mothers or six offspring developed tumours during 4 years of subsequent observation. At that time, three mothers and three offspring were given drinking-water containing phenobarbital at a concentration providing a dose of 15 mg/kg bw per day for the remainder of their lives or up to 43 months. Within less than 2 years, multiple hepatocellular neoplasms had developed in both offspring (5. Fifteen days later, four of the seven survivors were given drinking-water containing phenobarbital at a concentration providing a dose of 15 mg/kg bw per day for 9 months. Thus, pheno barbital is also an effective promoter of hepatocellular neoplasia in this non-rodent species (Rice et al. None of the rats exposed to phenobarbital only developed any thyroid tumours (Hiasa et al. Groups of 10 male and 10 female Fischer 344 rats, 4 weeks of age, received either a single intravenous injection of 0. At 2500 mg/kg of diet, a marked increase (about eightfold) in tumour yield was seen in male rats but a less than threefold increase in females. Papillary adenomas were seen in male rats only at 500 and 2500 mg/kg of diet phenobarbital (12% and 20%, respectively); only one female rat (4%) developed such a tumour when given 2500 mg/kg of diet. No thyroid tumours were found in control groups with or without phenobarbital treatment (Hiasa et al. Groups of 20 of these rats were castrated either at the beginning of the experiment or at the end of the second week and received the basal diet containing phenobarbital at 500 mg/kg from week 3 to week 40 of the experiment. The dose of T4 was required to maintain the normal thyroid gland weight in phenobarbital-treated rats and induced a slight increase in the serum concentration of T4 and a slight decrease in that of triiodo thyronine (T3). In male rats, phenobarbital increased the weight of the thyroid gland over that of controls (p 0. No significant differences were seen in the weights of the thyroid gland in female rats. None of the rats exposed to phenobarbital alone developed thyroid tumours (McClain et al. In the liver, pheno barbital is para-hydroxylated and subsequently conjugated (Butler, 1956). Phenobarbital N-glucoside, para-hydroxyphenobarbital and unchanged phenobarbital accounted for approximately 27, 19 and 29% of the dose, respectively (average for the two subjects) (Tang et al. Small amounts of the O-methylcatechol metabolite of phenobarbital were identified in the urine of a single individual given 300 mg orally (Treston et al. In patients with epilepsy receiving long-term treatment, 57% of the daily dose was recovered in urine, 14% as the N-glucoside, 16% as para-hydroxy phenobarbital and 27% as unchanged phenobarbital (Bernus et al. The major pathways for biotransformation of phenobarbital in rodents appear to involve para-hydroxylation, with excretion in either the free form or as a glucuronide conjugate. The N-glucoside of phenobarbital was formed at < 1% and excreted in urine only in mice; it was not detected in the urine of rats, guinea-pigs, rabbits, cats, dogs, pigs or monkeys (Soine et al. In addi tion to urinary excretion, 18% of a dose of 75 mg/kg bw phenobarbital was excreted in the bile of Sprague-Dawley rats within 6 h, the majority as conjugated metabolites (Klaassen, 1971). Very small amounts of meta-hydroxyphenobarbital, a 3, 4-dihydrodiol and a 3, 4-catechol derivative were also detected in the urine of rats and guinea-pigs given 110 and 56 mg/kg bw, respectively, by intraperitoneal injection (Harvey et al. When phenobarbital was administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg bw to beagle pups at 4, 10, 20, 40 and 60 days of age, no difference in the elimination half-time was observed with age, and there was no apparent formation of the para-hydroxylated meta bolite (Ecobichon et al. Most of the material excreted in urine was para-hydroxyphenobarbital and its conjugates, with lesser amounts of phenobarbital. The main effects of phenobarbital pretreatment on phenobarbital excretion in rats were increased urinary excretion of conjugated para-hydroxypheno barbital, a similar decrease in the excretion of the free form of this metabolite and no change in total phenobarbital excretion. In mice, phenobarbital pretreatment caused a threefold increase in the urinary excretion of the free form of para-hydroxypheno barbital, a small decrease in that of the conjugated form and about a twofold decrease in that of unchanged phenobarbital. The overall effect of phenobarbital pretreatment in mice appeared to be about a 50% increase in the amount of all forms of para-hydroxy phenobarbital, taking into account changes in urinary and faecal excretion. A minor urinary metabolite found in both species was not identified but was believed to be either the 3, 4-dihydrodiol or the 3, 4-catechol (Crayford & Hutson, 1980). The half-time for clearance of phenobarbital was decreased to one-third by 70 weeks in C3H/He mice given phenobarbital at a dose of 85 mg/kg of diet for up to 90 weeks (Collins et al. The formation and urinary excretion of the N-glucoside of phenobarbital appears to occur selectively in humans, with minor amounts excreted in mice but not in other species examined. Phenobarbital has produced irritability and hyperactivity in children and confusion in the elderly. Ohnhaus and Studer (1983) determined that an induction sufficient to increase antipyrine clearance by at least 60% was required to change steady-state thyroid hormone levels in phenobarbital-treated patients. The concentrations of circulating free T3 and free T4 were reported to be reduced in children with epilepsy maintained on phenobarbital, although clinical hypothyroidism was not seen (Yuksel et al. Since that time, extensive studies have been conducted on the enhancement by phenobarbital of cell proliferation in the liver and in hepatocytes in vitro. The effects of the drug on cell proliferation after initiation by a carcinogen have also been investigated and the cell proliferation rates compared in hepatocytes in altered foci and in surrounding tissue. In another experiment, young male Sprague-Dawley rats were treated intraperi toneally with 83 mg/kg bw phenobarbital daily for up to 5 days, and the hepatocyte labelling index was measured 24 h after the last injection (Peraino et al. The labelling index peaked at four times the control level in rats exposed to phenobarbital for 3 days and returned to control values by 5 days, despite continued phenobarbital administration. Phenobarbital increased the number and volume of eosinophilic and glutamyl transpeptidase-posi tive foci, but not of basophilic foci. The labelling indexes were increased in both the eosinophilic and basophilic foci in comparison with normal hepatocytes but were higher in the eosinophilic foci than in the basophilic foci. The index was not signifi cantly increased in phenobarbital-exposed normal hepatocytes over that in controls. Of the phenobarbital-exposed rats, 30% developed eosinophilic adenomas; the controls had none. The labelling index was increased several-fold in the livers of rats and mice of each sex at 1 week, but there were no increases at 5 weeks. The animals were treated with 500 mg/kg bw pheno barbital for 3, 7 and 14 days and evaluated for cell proliferation by measurement of radiolabelled thymidine. Phenobarbital enhanced cell proliferation in both species, with continued increases over the 14-day period. The investigators proposed that the increase in hepatocyte growth factor mediated phenobarbital-enhanced cell proliferation (Lindroos et al. Loss of normal cellular regulation of apoptosis has been shown to be an important component of the carcinogenesis process. Cell growth may increase due to an increase in cell proliferation and/or a decrease in cell death (apoptosis). Less apoptosis was seen in non-focal hepatocytes of fasted rats given phenobarbital (0. The labelling indexes in the testis, adrenal cortex and medulla, distal tubule of the kidney and exocrine pancreas were no different from those of controls. Significant decreases were observed in the labelling indexes in the pituitary and the endocrine pancreas (Jones & Clarke, 1993). An osmotic minipump containing radiolabelled thymidine was implanted in all animals at 24 weeks of age. After exposure to phenobarbital, significantly increased labelling indexes were found in hepatocytes in foci and in surrounding hepatocytes in females, but in males the increase was observed only in the surrounding hepatocytes. However, phenobarbital doubled the number of altered hepatic foci in C3H, but not in C3B6F1 mice. Phenobarbital increased the labelling index of eosinophilic, but not basophilic, foci in C3H mice. The greatest effect of pheno barbital was to decrease the labelling index in normal hepatocytes compared with cells in altered foci in C3H mice, in which the ratio of the labelling index in cells in foci and in normal hepatocytes was 214 for basophilic and 82 for eosinophilic foci without phenobarbital, and 545 for basophilic and 455 for eosinophilic foci with phenobarbital. The author concluded that the relative effect of phenobarbital on proliferation in cells of altered foci and normal hepatocytes was the main determinant of strain sensitivity to carcinogenesis (Pereira, 1993). Two solid hepatocellular carcinomas were found to have higher labelling indexes than the hyperplastic nodules from which they appeared to arise (Pugh & Goldfarb, 1978). Administration of phenobarbital for 10 days increased the labelling index several-fold, but this effect was no longer evident after exposure for 1 month.

Buy protonix 20mg with visa. Gastritis Symptoms -- Cause and its Symptoms!.

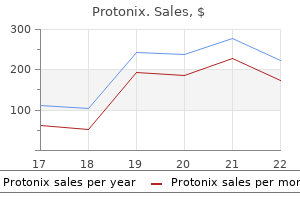

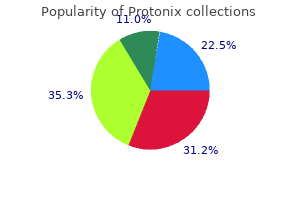

Until July 2008 gastritis nausea cure order protonix 20 mg without a prescription, administered at baseline gastritis diet avoid buy 40mg protonix free shipping, 6 months gastritis or pancreatic cancer cheap protonix 40mg with visa, 1 year chronic gastritis group1 order generic protonix canada, and annually thereafter gastritis diet cooking order 40 mg protonix. Beginning July 2008 alcoholic gastritis definition buy protonix visa, administered at 6 months, at 1 year, and annually thereafter. Dietician, social work services, Dietician, social work services and drug and drug discount program provided. Pharmacist on the Yes, part of Part D Pharmacy Management Yes, part of Part D Pharmacy Management program. Reuse of Reuse of dialyzers managed by dialysis dialyzers managed by dialysis center. Nutritional Oral nutritional and parenteral nutritional Oral nutritional supplements dialysis patients Supplements Provided supplements prescribed by physician. Parenteral nutritional supplements prescribed by physician cutoff based on physician order. Protocol Arbor Research Collaborative for Health 120 Final Report Appendices Component 2006 Response 2008 Response Benefits Offered as None. Team-Based Bedside Yes, at dialysis facility, as permitted by Yes, at dialysis facility, as permitted by Rounds Conducted Programs/Services Offered Patient Education Programs offered by Patient Education Programs offered by dialysis center and care coordination dialysis center and care coordination team. Electronic /Non-Electronic Electronic scale provided and other data Electronic scale provided and other data Home Monitoring Systems to moni tor weight gains of the pa tients to moni tor weight gains of the pa tients Used a t home. No regular program of access monitoring used in all program of access monitoring used in all areas, local surveillance may be areas, local surveillance may be provided. Nutritional Supplements Oral nutritional supplements provided to Oral nutritional supplements provided to Provided patients with albumin less than 3. Arbor Research Collaborative for Health 122 Final Report Appendices Component 2006 Response 2008 Response* QoL Survey Administration Not asked in 2006. In-Hospital Follow-Up Nephrologist provides in-hospital Nephrologist provides in-hospital se rvi ces. Advanced Care Directive Coordinated by the dialysis center social Coordinated by the dialysis center social Program worke r and the care management team. Information on treatment modality and transplants was extracted from the treatment history summary file. The United States Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Comparison Group the United States Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (U. Facilities were stratified for random selection based on standardized measures of mortality and hospitalization outcomes. For categorical variables, significance tests were performed for each level using a two-by-two Chi-Square test of the category versus all others. A few patients were new to Medicare the first year of their enrollment in the Demonstration. In these instances a risk score based only on demographic information from the current year was used. Line items with paid amounts less than or equal to $0 and unpaid claims were treated as corrections to matching claims or removed as appropriate. Claims data were subjected to a series of edits and validation checks to insure completeness and usability. Inpatient hospitalizations were extracted from the institutional claims using the presence of a diagnosis related group code or a place of service code of 22. When two Arbor Research Collaborative for Health 126 Final Report Appendices line items had the same date and provider identifier, these were considered duplicates and collapsed as one event. Hospitalizations where the admission and discharge dates were contiguous or overlapped were combined, retaining the earliest admission date and the latest discharge date. If any of the claims included diagnosis codes for cardiovascular disease, the record was flagged as a cardiovascular hospitalization. Total cost for an inpatient hospital stay was determined using total Medicare payment associated with the claim. When two line items had the same date and provider identifier, these were considered duplicates and collapsed as one event. If claims did not have a provider identifier, only line items with the same date and claim number were considered duplicates and collapsed. Medicare payments for line items on the claim without these codes were not included in the calculation of total cost. The average cost for each service in each year was calculated as the sum of the total cost of the service divided by the number of services. The variables were defined at a baseline of January for each year of the Demonstration so as not to be influenced by any prior enrollment decisions. By way of contrast, if one used data as of mid-year, those values might be influenced by the enrollment decisions made earlier in the year, introducing a bias due to endogeneity. The propensity matched samples were first used in the service utilization analyses in the Outcomes chapter (Chapter 11). Each analysis that used the propensity matched sample subsequently employed second stage multivariate regression modeling to adjust for any residual differences that persisted after propensity score matching. For the utilization and cost analyses, negative binomial regression was used to model counts of services. The negative binomial regression results are shown because these models generally fit the data better according to visual inspection of residual plots and examination of model deviance statistics. All models displayed adequate fit; however, models for some services fit better than others. In nearly every case, the absolute standardized differences were reduced to around or below 10% post-matching. Standardized differences above a 10% threshold are sometimes considered to indicate meaningful imbalance [1]. It should be noted, however, that given a large number of variables it is unlikely to achieve balance on every variable, particularly if the variable is not strongly related to the propensity of enrollment in the Demonstration given all other factors in the model. Therefore, most of the patients excluded from the matched samples did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the propensity score model. Inclusion in the propensity score model was determined based on the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients, whether the patients were Medicare Primary payor, and whether appropriate baseline data were available. Baseline was determined as January for each year of the Demonstration so as not to be influenced by any prior enrollment decisions. For example 93 patients did not have Medicare pay for their dialysis until after the January baseline month. We are grateful for this opportunity and have eagerly anticipated interim results that would demonstrate the potential benefits of this approach. In fact, as we reviewed findings throughout the report, and particularly in the important sections concerning utilization and cost results, we found significant issues that limit its overall utility. It is important to point these out so that subsequent evaluations can improve on the methods used here and deliver greater accuracy in their findings. Our three major concerns with the analyses contained within this report are that they: 1. Did not appropriately control for incident patients, limiting the ability to compare results to the matched control group 2. We outline below several technical enhancements which could lead to even more accurate and conclusive findings in the final report. Specifically, the match process to select control patients failed with respect to incident (new-to-dialysis) patients. According to the United States Renal Data System, the average Medicare dialysis patient costs $5, 882 per month. However, the average cost in the first month cost is significantly higher, at $14, 761. It is critical that any analysis of healthcare utilization or cost control for these differences in the first 6 months of dialysis. Unfortunately, the propensity score match utilized in the interim evaluation did not adequately control for this. While a Secondary Stage Regression Adjusted model was used in an attempt to correct these imbalances, it is unlikely that the regression model compensated for the large amount of remaining confounding resulting from the poorly constructed identification model used in the propensity score matching. This critical limitation of the propensity score match, which has been Arbor Research Collaborative for Health 141 Final Report Appendices acknowledged by the evaluators, need to be addressed in future evaluation efforts in order to understand the true impact of the disease management demonstration. Control for baseline healthcare resource utilization the best predictor of future healthcare resource utilization is past utilization. While the evaluation did include a measure of healthcare resource use as a variable in the propensity match, it limited it to one month, specifically January of each year. The month-to-month variation makes it difficult to draw any conclusions from a one-month observation, and likely introduces significant error into the match. A three to six month sample of healthcare resource use would provide significantly better statistical control. There is inherent potential for error in using such a model rather than using actual costs, and evidence of such error is included in the report. Of the two remaining demonstration participants, both have seen improved utilization and cost results in the last two years, and a final evaluation at the end of the program will allow the renal community to maximize its learning from this important experiment. In addition, we are working with an independent evaluator to reanalyze the current data and to conduct a final evaluation of the entire five-year demonstration, using the robust analytical approaches we believe are essential to producing the most accurate and appropriate conclusions on the clinical and financial outcomes of this project. Additional analysis of the experience during the last two years of the Demonstration period might provide insights not observed during the first three years. Therefore, the analytical methodology used several patient groups to serve as comparisons to the selected Disease Management interventions. These comparison groups were identified in order to be similar to the Demonstration groups, subject to availability of data. Some analyses utilized geographic-matched comparison populations, and others used a propensity score matched comparison population. For analyses evaluating the impact of Disease Management on processes of care, we accessed the United States Dialysis Outcomes Practice Patterns Study (U. Altogether, these methods for comparing the intervention group to a comparison population allowed for the evaluation of multiple endpoints including processes of care, clinical outcomes, service utilization, patient-centered measures, and financial outcomes. Finally, we utilized analytical tools that took into account clinical and demographic factors that would be expected to impact findings for the respective endpoints evaluated. The Evaluation Report notes both strengths and potential limitations for interpreting the findings, such as differential disenrollment rates, and limitations of the propensity score methodology. However, it is also necessary to draw the most accurate conclusions possible from the existing data recognizing the potential uncertainties in those conclusions. Many different specific methodologies could have been used in this demonstration evaluation, as in the general analysis of research questions. As described below, multiple methods were used to test several of the research questions. In these instances, the different methods yielded consistent results, suggesting that the results are relatively robust to the method used to carry out the analysis. Various clinical and demographic factors were taken into account in the propensity score method. Our examination of the improvement in comparability of propensity score matched populations shows reduced bias overall and is consistent with published literature evaluating success of the propensity score matching process [1]. In summary, while there is some evidence for residual differences in the groups, there does not appear to be evidence for a large amount of remaining confounding. Nonetheless, we have included supporting analyses and substantial text on these issues in the report. These models provide for direct statistical adjustment for characteristics that continued to differ after the propensity score methodology. While these models are inherently limited Arbor Research Collaborative for Health 144 Final Report Appendices by application after the propensity score methodology, there is no reason to believe these models failed to statistically adjust for observed residual differences. Regarding controlling for baseline healthcare resource utilization: One important control used in the analysis was to adjust for baseline levels. Measuring baseline utilization over a longer time period has the potential to improve the accuracy of the propensity score models for some patients. However, use of a longer baseline period would not be expected to reduce bias in the results but would primarily increase precision in the estimates.

From a variety of studies gastritis diet rice buy generic protonix 20mg, no quantitative relationship had been demonstrated between the degree of torpor (that is gastritis diet 91352 protonix 40 mg overnight delivery, the stage on the continuum from full alertness to unconsciousness) and the development of deper sonalization gastritis diet garlic 40 mg protonix sale. On studying the performance of depersonalized subjects on psychosomatic tests gastritis of the antrum generic protonix 20mg visa, there did not appear to be evidence to support a specifc relationship between clouding of con sciousness and depersonalization gastritis diet honey discount protonix. There appeared to be many individuals who gastritis diet x factor protonix 20 mg without prescription, despite various types of assault on their brains, never developed depersonalization. From this information, Sedman (1970) concluded that: there may well be a built in preformed mechanism in approximately 40 per cent of the population to exhibit depersonalization; that the factors which initiate such a response are not specifcally those associated with clouding of consciousness; or where clouding of consciousness appears to be playing a part, it may well be the presence of another common factor that is more relevant. Thus, the relationship between depersonalization and brain pathology remains unclear. Depersonalization is certainly not pathognomonic of organic diseases; in fact, there is no organic or psychotic abnormality in the vast majority of sufferers. The lack of emotional colouring, reported as feelings of unreality, would be accounted for by a left-sided prefrontal mechanism with inhibition of the amygdala. Other authorities describe left-hemispheric fronto-temporal activation coupled with decreased left caudate perfusion (Hollander et al. Thus, it occurs following the ingestion of alcohol or drugs, especially psychotomimetics such as lysergic acid diethylamide (Sedman and Kenna, 1964), mescaline, marijuana or cannabis (Szymanski, 1981; Carney et al. It is also described as a side effect with prescribed psychotropic drugs such as the tricyclic antidepressants, but because of the common association between depersonalization and depression it is diffcult always to attribute cause. Additionally, there is evidence of widespread meta bolic alterations in the sensory association cortex as well as prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic inhibition in response to aversive stimuli (Simeon, 2004). Furthermore, there is association with childhood interpersonal trauma, particularly emotional maltreatment (Simeon et al. In fact, passivity experiences have even been described as a variant of depersonalization. However, Meyer (1956), as cited by Sedman (1970), has distinguished schizophrenic ego disturbances from depersonalization on phenomenological grounds; that is, on the description by the patient of his own internal experience. It is, of course, well recognized that true depersonalization symptoms do occur in schizophrenic patients, especially in the early stages of the illness, alongside defnite schizophrenic psychopathology. Depersonalization is commonly described in manic-depressive disorder; however, the symp toms occur only in the depressive phase and there are no references to depersonalization occurring in mania (Sedman, 1970). Anderson (1938) considered that ecstasy states occurring in manic depressive disorders were the obverse of depersonalization and that, while the former occurred in mania, the latter occurred in depression. Sedman (1972), in an investigation of three matched groups, each of 18 subjects with depersonalization and depressive and anxiety symptoms, con sidered that the results stressed the importance of depressed mood in depersonalization, while anxiety seemed to carry no signifcant relationship. Many other authors have stressed the close association between the symptoms of deperson alization and anxiety. For instance, Roth (1959, 1960) described the phobic anxiety depersonaliza tion syndrome as a separate nosological entity, but saw it as a form of anxiety on which the additional symptoms are superimposed in a particular group of individuals. He considered deper sonalization to be more common with anxiety than with other affective disorders, for example depression. The patient, most often female, married and often in the third decade of life, has a great fear of being conspicuous in an embarrassing way in public, for example fainting or being taken ill suddenly on a bus or in a supermarket. Fear of leaving the house unaccompanied develops from this, so that the patient is frightened of being at a distance from familiar surroundings without some supporting fgure to whom she can turn. She may feel panicky on her own at home and so keeps her child off school, a potential precipitating factor in subsequent school refusal. The symptom of dizziness is a very common complaint and frequently results in referral to ear, nose and throat departments. Although depersonalization is commonly described in association with agoraphobia, other phobic states, panic disorder, various types of depressive condition, post-traumatic stress disorder and other non-psychotic conditions, it may also appear as a pure depersonalization syndrome, and Davison (1964) has described episodic depersonalization in which other aetiological factors or co-morbid disorders are not prominent. In psychoanalytic theory, depersonalization has taken on a rather different meaning, and therefore there are different explanations for its origin. Psychoanalysts have been less concerned with describing the phenomena than the underlying concept of the alienation of the ego. For example, in the work of the existentialist school, as typifed by Binswanger (1963), there is discus sion of the depersonalization of man. Theoretical constructs dispose him, rather, to speak instead of my, your, or his Ego wishing something. This clearly is quite a different sense of the word than the phenomenological, with which this chapter has been concerned. The distressing experience of depersonalization, with a feeling of unreality, remains central to the description of the disordered self. The disturbance that causes this may be organic or environmental, psychotic or existential. Concern about the experience of self and of the environ ment most commonly occur together. Grigsby J and Kaye K (1993) Incidence and correlates of depersonalization following head trauma. Michal M, Kaufhold J, Grabhorn R, Krakow K, Overbeck G and Heidenreich T (2005) Depersonalization and social anxiety. Ross C (1997) Dissociative Identity Disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Features and Treatment of Multiple Personality. Schilder P (1935) the Image and Appearance of the Human Body: Studies in the Constructive Energies of the Psyche. Sedman G (1972) An investigation of certain factors concerned in the aetiology of depersonalisation. Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, Sirof B and Knutelska M (2001) the role of childhood interpersonal trauma in depersonalization disorder. Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D and Guralnik O (2003) Feeling unreal: a depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. Sims A and Sims D (1998) the phenomenology of post-traumatic stress disorder: a symptomatic study of 70 victims of psychological trauma. Zikic O, Ciric S and Mitkovic M (2009) Depressive phenomenology in regard to depersonalization level. This page intentionally left blank C H A P T E R 14 Disorder of the Awareness of the Body Summary the body is the physical manifestation of the individual being. Even though these abnormal experiences are disparate, what binds them together into a coherent aspect of psychopathology is that the body as experienced is at their heart. Auden (1969) the physicality of the body is ever present: there is density, mass, movement, action, speed, position, heat, cold and various degrees of touch, pain and so on. Materialist theories propose that the body is all there is, and variations of these theories account for mind in different ways, whereas idealist theories make the opposite claim that the mind is all that exists. Whether these metaphors originally derive from the physical manifestations of emotional distress or whether the language, that is, the metaphor, structures the experience is a moot point. What is clear is that there is no ready division between the subjective experience of self and of body. In order to form a cohesive framework for conceptualizing the disorders of self and the very diverse abnormalities of body image, one needs to apply the methods of descriptive psychopathol ogy. In Chapter 12, the nature of self and the pathology of the experience of self were discussed. Classifcation Cutting (1997) gives a good outline of the classifcation of disorders of awareness of the body, which has been adapted for this chapter (Table 14. There are disorders of beliefs about the body including beliefs of illness, disease and death (see below). In this group are also the disorders of dissatisfaction with the body, which occur in eating disorders. These dissatisfactions with the body are best understood as arising from negative cognitive evaluations, that is, beliefs about the body. Next, there are disorders of bodily function, including the loss of sensory, motor or cognitive function that occurs in the dissociative disorders. There are disorders of the experience of the physical characteristics of the body. These include disorders of the experience of the size, shape, structure or weight of the body. And, fnally, there are complex disorders of the sensory experience of the body that almost exclusively derive from neurological lesions. Disorders of Beliefs About the Body (Bodily Complaint Without Organic Cause) Classifcation of these disorders is diffcult, partly because the symptoms are obscure in origin and partly because there are different theoretical bases for the words used. For example, conversion hysteria was used as a term that referred to the presumed unconscious conversion of an unaccept able affect into a physical symptom. Hypochondriasis refers to a concern with symptoms and with illness that the outside observer regards as excessive; the same amount of concern or complaint associated with pathology that the doctor regards as justifying it would not be deemed hypo chondriacal. Dysmorphophobia is a phenomenological term and refers to the subjective experience of dissatisfaction with bodily shape or form ure 14. These expressions of dissatisfaction may occur on their own or in any combination, and they can affect any bodily system or psychological process. Only a minority come to medical attention, and only a selected atypical proportion of these are seen by psychiatrists. There is a distinction between illness fears, when there are no bodily symptoms, and the fears and distress which are not associated with bodily symptoms but merely arise out of the possibility of serious illness. This shows the overlap between illness phobias (unreasonable fear of developing illness) and hypochondriasis (preoccupation with symptoms). There is often diffculty in diagnosis when a person with demonstrable physical pathology complains excessively about his symptoms; his complaints appear to be out of proportion to the anticipated suffering and disability of the illness. Somatic symptoms without organic pathology are extremely common and may result from misunderstanding the nature and signifcance of physiological activity aggravated by emotion (Kellner, 1985). Explicit in the identifcation of hypochondriasis is the condition of the patient himself. Implicit, however, is the doctor who labels his patient hypochondriacal and deems him sick. What the symptoms communicate to other people is an important component of all disorders of bodily awareness; concentration on the subjective aspects of symptoms should not detract from their social implications. By derivation, the word hypochondrium refers to the anatomical area below the rib cage ure 14. Such words as atrabilious or melancholia refer to the black bile that was considered to be associated with hypochondriacal complaint and depressed mood. Kenyon (1965) has defned hypochondraisis as morbid preoccupation with the body or state of health. It is best to regard hyponchondriasis as a symptom rather than a distinct condition. The content is the excessive concern with health, either physical or mental and the interpretation of subjective experience as deriving from serious illness. Even though the term hypochondriacal is best retained as description rather than as a discrete disease entity (Kenyon, 1976), both current classifcation systems have a purely hypochondriacal disorder. These concepts are not alternatives but are all present to a different extent in the individual sufferer. Some individuals use a somatic style to describe their perception of internal discomfort. Appleby (1987) points out that closer exami nation reveals a descriptive triad of the patient being convinced that he has a disease, fearing the disease and being preoccupied with his body. He emphasizes that the patient needs to understand his symptoms before any improvement can be expected. Bridges and Goldberg (1985) have assessed somatic presentation of psychiatric disorder in primary care in a series of 500 inceptions to illness among 2, 500 attendees. Their operational criteria for somatization were as follows: Consulting behaviour: seeking medical help for somatic manifestations and not presenting psychological symptoms. These authors consider that somatization is a common mode of presentation of psychiatric illness and partly explains the failure of family doctors to detect psychiatric disorders in primary care.